Executive Summary: The Psychology of the Shadow

The Core Concept: The “Shadow” is not just the “evil” part of you; it is everything you have disowned to survive. It contains your unexpressed rage, your hidden shame, but also your unclaimed creativity and power (The Golden Shadow).

Key Mechanisms:

- Projection: We see our shadow in others. If you irrationally hate someone, they likely embody a trait you have repressed in yourself.

- The Acorn Theory: James Hillman’s idea that you are born with a unique destiny (an acorn) that you must uncover beneath the layers of social conditioning.

- Growth as Trauma: Real growth requires the “death” of the old ego. This is why we resist change even when we say we want it.

Clinical Application: Shadow work is essential for treating addiction, complex trauma, and “Nice Guy/Girl” syndrome.

How to Find Your Shadow Before Your Shadow Finds You: A Guide to Jungian Integration

Carl Jung famously said, “Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”

When I switch to a Jungian orientation with a patient, I tell them about the “Acorn Theory”. I explain that inside them is a dormant acorn that knows exactly what kind of oak tree it is supposed to be. It has a map of its own potential. However, most people stop listening to their acorn early in life. They become too scared, too overwhelmed, or too resigned to the rules of their family and culture. They die as saplings, never knowing who they were meant to become.

This article explores how we lose touch with our true selves, how we create a “Shadow,” and how we can reclaim the lost parts of our soul before they destroy us from the subconscious.

Part I: The Architecture of the Shadow

We are not born with a Shadow; we create it.

As children, we are whole. We cry when we are sad, scream when we are angry, and laugh when we are happy. But then, the socialization process begins.

The Rules of the Family

Our parents and culture teach us what is “acceptable.”

* “Boys don’t cry.” (Sadness is pushed into the Shadow).

* “Nice girls don’t get angry.” (Aggression is pushed into the Shadow).

* “We don’t talk about money.” (Ambition is pushed into the Shadow).

We learn to split ourselves. We keep the “acceptable” parts in the light (the Persona) and shove the “unacceptable” parts into the dark (the Shadow).

But these parts do not die. They grow in the dark. The anger you repressed becomes a seething resentment. The ambition you hid becomes envy of others’ success. The sadness you denied becomes a chronic, low-level depression.

Part II: How the Shadow Shows Up

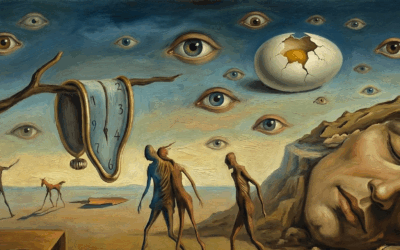

The Shadow is like a beach ball held underwater. You can hold it down for a while, but eventually, your arm gets tired, and it pops up with tremendous force. Here is how to spot it:

1. Projection (The Mirror Effect)

The easiest way to find your shadow is to look at who you hate.

If you have a visceral, irrational reaction to someone—someone who is arrogant, lazy, or loud—it is likely because they are acting out a part of you that you have forbidden.

- If you repress your own selfishness, you will be enraged by selfish people.

- If you repress your own sexuality, you will be judgmental of others’ promiscuity.

We force others to carry the parts of ourselves we cannot bear to hold. Jungians call this Shadow Projection.

2. Dreams and Nightmares

In dreams, the shadow often appears as a dark figure, a stalker, or a monster.

* The Stalker: Represents a part of you that is trying to catch up with your conscious ego.

* The Basement/Attic: Often represents the unconscious storage of memories or traits.

* The Intruder: Represents a truth you are trying to keep out of your awareness.

3. The “Slip”

The Shadow emerges when our ego strength is low—when we are drunk, tired, or stressed. We say things we “didn’t mean.” We act out sexually or aggressively. Afterwards, we say, “I don’t know what came over me.”

Jung would say: “It wasn’t you; it was your Shadow.”

Part III: The World Shadow vs. The Self Shadow

It is important to distinguish between two types of Shadow material.

- The Self Shadow: These are the personal traits you have disowned (e.g., “I am not a jealous person”).

- The World Shadow: These are the existential truths about life that you refuse to accept (e.g., “Bad things happen to good people,” or “I will die one day”).

Trauma often forces us to confront the World Shadow. When a patient tells me, “I can’t believe this happened to me,” they are grappling with the shattering of their innocent worldview. Healing requires integrating the reality that the world is dangerous and unfair, while finding the strength to live in it anyway.

Part IV: How to “Eat Your Shadow”

So, how do we integrate these parts? Jung called this process “Eating the Shadow.” It means taking back the energy you have projected onto others.

1. Identify the Trigger

Notice when you have an out-sized emotional reaction. If your boss’s arrogance makes you want to scream, ask yourself: “Where in my life am I arrogant? Or where do I wish I could be arrogant but don’t let myself?”

2. Dialogue with the Part (IFS)

Using techniques from Internal Family Systems (IFS), we can talk to the Shadow.

Instead of banishing the “Lazy Part,” ask it: “What are you trying to do for me?” You might find that the “Lazy Part” is actually a “Rest Part” trying to save you from burnout.

3. Ritual and Art

The Shadow speaks in symbols, not logic. Drawing, painting, or Active Imagination can give the Shadow a safe outlet. If you have repressed rage, draw a picture of a volcano. Give the energy a form so it doesn’t have to act out in your behavior.

Conclusion: Growth is a Kind of Death

I tell my patients that growth is trauma. To become the person you are meant to be, the person you are right now must die. You must let go of your old identity—the “Nice Guy,” the “Victim,” the “Perfect Mother”—to make room for the whole, messy, complex human being you actually are.

If you do not face your Shadow, it will find you. It will find you in a mid-life crisis, an affair, an addiction, or a sudden collapse. But if you turn to face it, you will find that it is holding the very gold you need to become whole.

Explore Jungian & Shadow Work

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Understanding Archetypes

The Warrior: Action & Boundaries

The Lover: Passion & Connection

The Magician: Knowledge & Transformation

Practical Shadow Work

Bibliography

- Jung, C.G. (1991). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Routledge.

- Hollis, J. (1998). The Eden Project: In Search of the Magical Other. Inner City Books.

- Edinger, E. F. (1992). Ego and Archetype: Individuation and the Religious Function of the Psyche. Shambhala.

- Zweig, C., & Abrams, J. (1991). Meeting the Shadow: The Hidden Power of the Dark Side of Human Nature. Tarcher.

- Johnson, R. A. (1993). Owning Your Own Shadow: Understanding the Dark Side of the Psyche. HarperOne.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!

Yeah hundred s of articles on the blog.