Maurice Merleau-Ponty: The Philosopher of the Body and the Flesh of the World

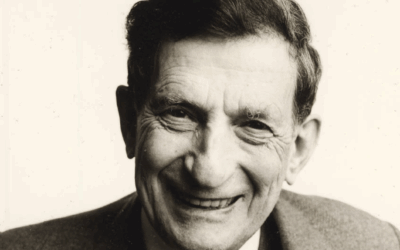

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) stands as a pivotal figure in 20th-century thought, a French phenomenologist who dared to challenge the ancient dualism separating the mind from the body. While his contemporary Jean-Paul Sartre focused on radical freedom and consciousness, Merleau-Ponty focused on the Body—not as a biological machine, but as the very ground of our existence.

His work bridges the gap between the abstract world of philosophy and the concrete realities of psychology and neuroscience. Merleau-Ponty argued that we do not have bodies; we are bodies. This insight has profound implications for psychotherapy, particularly in somatic and trauma treatments where the body “keeps the score.” In this comprehensive guide, we explore his revolutionary ideas on perception, the “lived body,” and the mysterious concept of “The Flesh.”

1. The Primacy of Perception

In his magnum opus, Phenomenology of Perception (1945), Merleau-Ponty dismantled the idea that perception is just a camera taking pictures for the brain to analyze. He argued that perception is an active, embodied engagement with the world.

1.1. Beyond Empiricism and Rationalism

Merleau-Ponty rejected two dominant views:

* Empiricism: The view that we just receive sensory data (like a camera sensor).

* Rationalism: The view that the mind organizes chaos into order (like a computer processor).

Instead, he proposed that the body is meaning. Before we think about a cup, our hand already knows how to hold it. This “pre-reflective” knowledge is the foundation of all thought.

1.2. The Phenomenal Field

He introduced the concept of the Phenomenal Field—the world as it appears to us in lived experience, before science dissects it. In this field, objects are not isolated; they are part of a web of meaning. A “chair” isn’t just wood and fabric; it is “something-to-sit-on.” It invites the body to act. This aligns closely with the concept of Intentionality found in Husserl, but grounds it in physical action.

2. The Lived Body (Le Corps Propre)

This is Merleau-Ponty’s most famous contribution. The “Lived Body” is not the body you see in the mirror or the anatomy textbook; it is the body as you live it.

2.1. I Am My Body

Descartes famously said, “I think, therefore I am.” Merleau-Ponty countered with, “I can, therefore I am.” Our existence is defined by our physical capacities. When a person learns to drive, the car becomes an extension of their body. They “feel” the road through the wheels. This plasticity of the body schema is now a core concept in neuroscience (neuroplasticity).

2.2. The Body in Trauma

In therapy, trauma often manifests as a disruption of the Lived Body. The body becomes an object of pain or fear, rather than a vehicle of agency. Treatments like Somatic Experiencing and Brainspotting are essentially applied phenomenology—helping the client reclaim their “Corps Propre” from the grip of the past.

3. The Flesh of the World (La Chair)

In his final, unfinished work, The Visible and the Invisible, Merleau-Ponty introduced a mystical and ontological concept: The Flesh.

He argued that the boundary between the “Self” and the “World” is not a wall, but a membrane. We are made of the same “stuff” as the world. When we touch a hand, we are both touching and being touched. This reversibility suggests that the universe is not a collection of dead objects, but a living, breathing web of connection. This concept resonates deeply with Jung’s Unus Mundus and the ecological philosophy of David Abram.

4. Merleau-Ponty’s Legacy in Science and Culture

4.1. Cognitive Science and Embodiment

Merleau-Ponty anticipated the “Embodied Cognition” revolution by 50 years. Modern researchers like Francisco Varela and Louise Barrett cite him as a founding father. We now know that higher reasoning depends on the sensory-motor system—we literally “grasp” ideas.

4.2. Art and Aesthetics

He wrote extensively on painting, particularly Cézanne. He believed artists do not copy the world; they make visible the invisible act of perception. This links his philosophy to the psychology of color and visual perception.

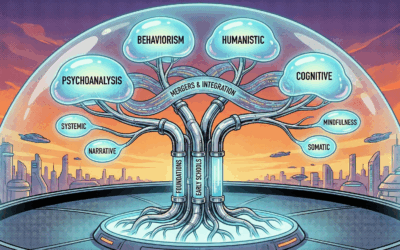

Explore the Philosophy of Embodiment

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

The Phenomenological Tradition

- Edmund Husserl: The father of phenomenology and Merleau-Ponty’s teacher.

- Martin Heidegger: Being-in-the-world and the existential turn.

- Jean-Paul Sartre: The philosophy of radical freedom.

- Gaston Bachelard: The poetics of space and elements.

- Paul Ricoeur: Hermeneutics and the narrative self.

Embodiment in Anthropology and Ecology

- David Abram: The Spell of the Sensuous and ecological phenomenology.

- Louise Barrett: Beyond the brain—cognition in the wild.

- Allan Schore: The development of the self through bodily attunement.

Related Philosophers of Mind and Space

- Henri Bergson: Vitalism and the intuition of time.

- Peter Sloterdijk: Spheres, spaces, and immunological bubbles.

- Gilbert Durand: The anthropological structures of the imaginary.

- Michel Foucault: The body as a site of power and discipline.

Bibliography

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945). Phénoménologie de la perception. Gallimard. [English translation: Phenomenology of Perception (2012). Routledge.]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1964). Le Visible et l’invisible. Gallimard. [English translation: The Visible and the Invisible (1968). Northwestern University Press.]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1964). L’Œil et l’esprit. Gallimard. [English translation: Eye and Mind (1993). Northwestern University Press.]

- Carman, T. (2008). Merleau-Ponty. Routledge.

- Gallagher, S. (2005). How the Body Shapes the Mind. Oxford University Press.

- Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. MIT Press.

0 Comments