What happened to the forgotten model of psychotherapy?

Abstract and Main Ideas:

1. Transactional Analysis, developed by Eric Berne, gained rapid popularity in the 1960s but declined quickly thereafter.

2. TA was influenced by game theory and reflected the zeitgeist of the mid-1960s.

3. The model was initially popular among both traditional psychoanalysts and experiential therapists.

4. TA’s decline was partly due to its association with controversial practices like re-birthing therapy.

5. Currently, few accredited TA practitioners remain, but its concepts are still used in business, industrial psychology, and relationship theory.

6. TA’s theoretical framework is based on three ego states: Parent, Adult, and Child.

7. The model assumes that people engage in subconscious “games” or transactions with predictable outcomes.

8. TA aims to help clients inhabit the Adult ego state more often, as it’s considered the most adaptable and desirable state.

9. Berne identified over 100 “games” in his work, such as “If it Weren’t for You.”

10. While the specific games may not be widely used today, the concept of understanding underlying motivations in interactions remains valuable.

11. TA has influenced other therapeutic approaches like Redecision Therapy and Narrative Therapy.

12. The language and concepts of TA continue to be used by some eclectic therapists to help clients understand relationship patterns.

13. TA’s popularity in pop culture outlasted its prominence in clinical practice.

14. The model aimed to simplify and expand upon Freudian concepts, making them accessible to non-professionals.

15. Despite criticism as “pop psychology,” TA initially gained respect in academic circles before its decline.

Article:

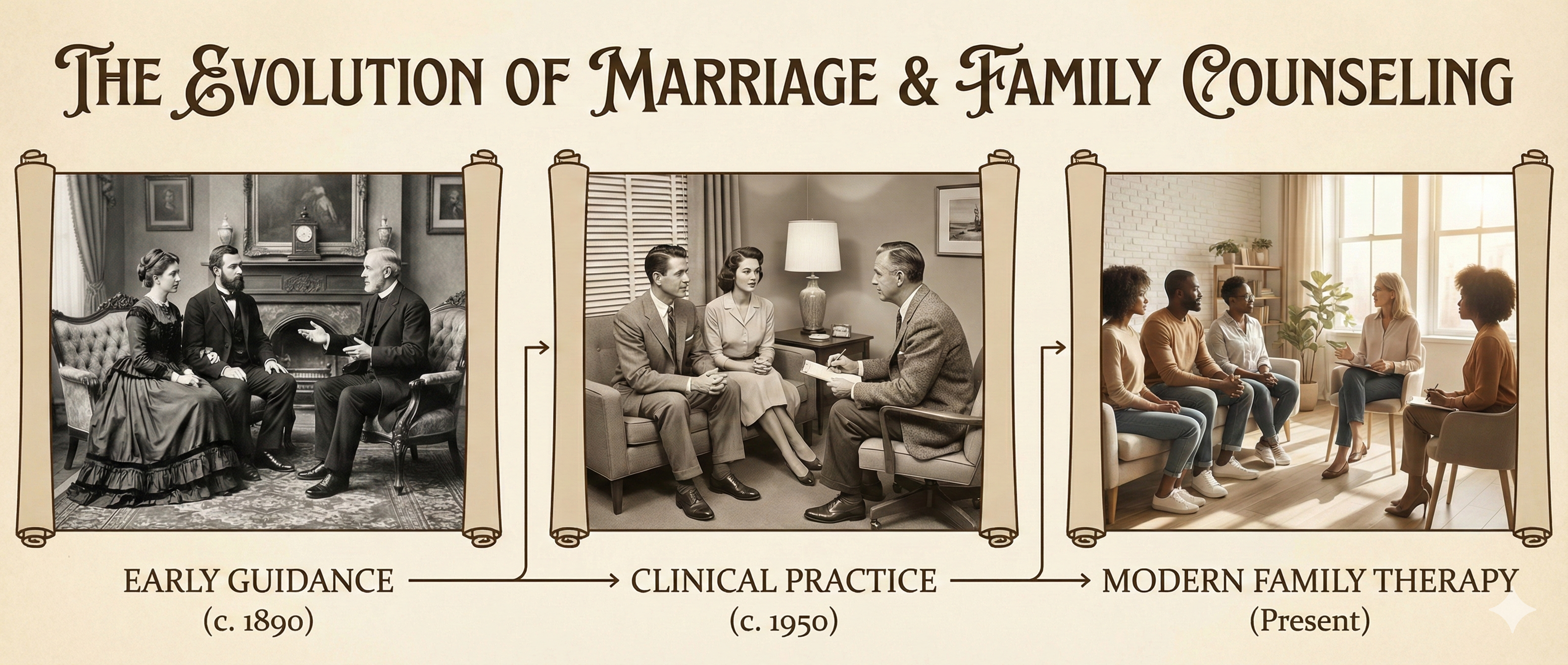

There are few models of psychotherapy that have flared in popularity and waned as quickly as Transactional Analysis. Eric Berne introduced the world to Transactional Analysis as a model of psychotherapy with the publication of The Games People Play in 1964. TA was a deliberately post Freudian, or extra Freudian as Berne would point out, in that it expanded on Freud’s concepts that were the most popular in the early sixties and simplified them to be comprehensible to non professionals at the same time. Game theory, the idea that math models could explain interactions in biology and consciousness, had been developed in the early 1950s during the cold war. The fact that this theory was entering public consciousness during Berne’s first papers theorizing TA cannot be discounted as a strong influence on the conception of TA and as a reason for its popularization.

TA’s assumptions about the psyche were closely highly reflective of the zeitgeist of the mid 60’s, and this partially explains its meteoric rise . The Games People Play was immediately a best seller upon its release. Despite criticism at the time that the book was “pop psych” that made the general public feel like they could play psychoanalyst, The Games People Play commanded respect in the academic community as well until the late seventies. TA was, at its zenith, an extremely popular model for both traditional psychoanalytic practitioners and even experiential and Gestalt therapists. The decline of the model can be attributed partially to Berne’s hesitancy to disavow any practitioner using the TA model. TA suffered many setbacks to its credibility, most notably when TA practitioners became notorious using the method as a part of pseudo-scientific re-birthing movement, injuring and killing several children.

Perhaps it is fitting that a model of Psychotherapy assembled from pieces of the popular culture, lives on in popular culture more than it lives on in clinical culture. Even though the International Transactional Analysis Association still accredits professionals who use the model, at the time of this writing there are only 22 credentialed TA practitioners left in the world, and all of those accredited practice in the US. Redecision Therapy, and Narrative Therapy, are the most widely used styles that borrow heavily from Berne’s model.

Much of the language of Berne’s model and his ideas occupy space in the worlds of business, industrial psychology, and family and relationship theory. All though there are few purists left it is not uncommon for eclectic therapists to use the language of TA to help clients parse the patterns in their relationships.

The theoretical framework of TA assumes both that there are subconscious “games” that explain common repeated human interactions and that persons will inhabit one of three egos states during these games. The ego states that Berne describes are

Parent – The parent ego state contains the beliefs and behaviors that we have been taught are correct. The parent ego state is not the same for all patients because it contains the attitudes and opinions of their own caregivers and not all caregivers behave the same. The parent ego state inflexible and legalistically enforces the standards of patients caregivers on themselves and other parties during times of stress and confusion.

Adult – The adult ego state contains what patients have learned from their own experience. The adult ego state is the most desired and adaptable state because it is capable of borrowing useful behaviors from the child and parent ego state while ignoring the self defeating behaviors and needs of theses states. Inhabiting the adult ego state during our interactions with others is the goal of the TA. Clients cannot act on the things that they have learned in therapy unless they have access to this state.

Child – The child ego state is comprised of what we feel. The child ego state is reactionary and wants to indulge base emotions. It wants to express anger, sadness and fear in the active state. The child ego state leads patients to take direction to others and seek to be understood, even when that behavior is not in their best interest.

Games

The games in TA are “transactions” in which all parties are following an unconscious script towards a desired predictable outcome where each party will receive an unconscious reward. Here the reward will be the fulfillment of needs from the parent or child ego states. The games of TA are all played without our adult awareness and the rewards received by the parties in the game are agreed upon unconsciously by all parties of the game when it begins.

One of the most common games that Berne identified was If it Weren’t for You. In this game, Person A has a subconscious fear of pursuing some goal. Person A selects Person B as a romantic partner, knowing that they the requirements of their relationship will prevent them from pursuing their goal. Person A not only receives the reward of avoiding their fear, but also gets to vent their frustration with themselves onto a willing target. Berne identifies over a hundred games in his TA books. Transactional analysis practitioners were trained to look for the games being played in when client’s came into sessions and bring them into the clients awareness.

I have never found it helpful to try and fit my clients interactions onto the requirements of any of Berne’s games. However, I do find it useful to make clients aware that what another person says they want is not always what they want. Patients who are experiencing problems with colleagues, family members, and spouses can often have better relationships when they become aware of what it is that people actually want, and want to avoid, in the transactions that they have with them.

Bibliography:

Berne, Eric. Games People Play: The Psychology of Human Relationships. Grove Press, 1964.

Berne, Eric. Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy: A Systematic Individual and Social Psychiatry. Grove Press, 1961.

Harris, Thomas A. I’m OK, You’re OK. Avon, 1969.

Steiner, Claude. Scripts People Live: Transactional Analysis of Life Scripts. Grove Press, 1974.

Karpman, Stephen B. “Fairy Tales and Script Drama Analysis.” Transactional Analysis Bulletin, vol. 7, no. 26, 1968, pp. 39-43.

Further Reading:

Goulding, Robert, and Mary Goulding. Changing Lives Through Redecision Therapy. Grove Press, 1979.

Stewart, Ian, and Vann Joines. TA Today: A New Introduction to Transactional Analysis. Lifespace Publishing, 1987.

Dusay, John M. “Egograms and the Constancy Hypothesis.” Transactional Analysis Journal, vol. 2, no. 3, 1972, pp. 37-41.

English, Fern. “Rackets and Real Feelings.” Transactional Analysis Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, 1971, pp. 15-18.

Kahler, Taibi, and Herbert A. Capers. “The Miniscript.” Transactional Analysis Journal, vol. 4, no. 1, 1974, pp. 26-42.

Mellor, Ken, and John Schiff. “Discounting.” Transactional Analysis Journal, vol. 5, no. 3, 1975, pp. 295-302.

Drego, Pat. “The Cultural Parent.” Transactional Analysis Journal, vol. 13, no. 4, 1983, pp. 224-227.

Clarkson, Petruska. “The Bystander (The Observer) Role in the Drama Triangle.” Transactional Analysis Journal, vol. 22, no. 4, 1992, pp. 189-196.

Novellino, Maurizio. “The Cultural and Intrapsychic Functions of Transactional Analysis.” Transactional Analysis Journal, vol. 28, no. 1, 1998, pp. 31-36.

0 Comments