In 1981, Judith Lewis Herman published a book that would be called “a landmark study” and “one of the most important works of the decade”: Father-Daughter Incest. Based on extensive research including interviews with forty incest survivors and their family members, the book shattered prevailing psychological theories portraying incestuous fathers as weak, passive men dominated by seductive wives and daughters. Instead, Herman documented a clear pattern: authoritarian fathers wielding power over subordinated families, using violence and threats to maintain control, and exploiting daughters in households where mothers were often physically or emotionally absent, ill, or themselves victims of abuse.

The book challenged Sigmund Freud’s abandonment of the seduction theory—his early insight that many patients’ psychological difficulties stemmed from actual childhood sexual abuse, which he later reframed as fantasy and wish-fulfillment rather than reality. Herman argued this theoretical reversal had profoundly damaged psychology’s ability to recognize and address real abuse. By dismissing survivors’ accounts as fantasy, psychoanalysis had abandoned precisely those patients most needing help.

Father-Daughter Incest established Herman as major voice in understanding trauma, abuse, and recovery. But her most influential contribution came eleven years later with Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror, published by Basic Books in 1992 and updated with new afterwords in 1997 and 2015. This landmark work would fundamentally reshape how mental health professionals understand and treat psychological trauma.

A Revolutionary Vision of Trauma

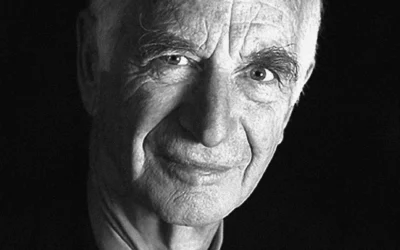

Judith Lewis Herman, M.D., Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard University Medical School and Director of Training at the Victims of Violence Program in Cambridge, Massachusetts, brought unique perspective to trauma study. Her background in both psychoanalysis and feminist theory enabled her to see patterns others missed: the psychological aftermath of domestic violence mirrored combat trauma, childhood abuse created symptoms indistinguishable from political torture, and rape survivors experienced the same dissociative responses as war veterans.

In Trauma and Recovery, Herman documented these connections with scholarly rigor and compassionate clarity. Drawing on research and clinical experience with combat veterans, abuse survivors, and political prisoners, she demonstrated that trauma transcends specific contexts while maintaining common psychological features. Whether trauma stems from battlefield combat, childhood sexual abuse, domestic violence, or political oppression, survivors face similar challenges: intrusive memories, hypervigilance, emotional numbing, difficulty trusting others, and profound disconnection from self and world.

The book’s power lay partly in Herman’s historical analysis. She traced how society’s willingness to acknowledge trauma ebbs and flows based on political forces. After World War I, “shell shock” gained medical recognition, then faded from view. Vietnam veterans’ struggles forced PTSD into the DSM-III in 1980. The feminist movement’s documentation of widespread sexual violence and domestic abuse created new understanding of previously dismissed suffering. Herman showed how trauma recognition requires social movements willing to bear witness to atrocity—and how easily that recognition vanishes when political will recedes.

The Three Stages of Recovery

Herman’s most enduring clinical contribution in Trauma and Recovery was articulating trauma recovery’s three fundamental stages, a framework that transformed clinical practice worldwide.

Stage One: Safety and Stabilization

Herman insisted recovery must begin with establishing safety. For trauma survivors whose world shattered into danger and unpredictability, creating stable foundation takes precedence over processing traumatic memories. This means ending ongoing victimization, establishing physical safety, developing emotional regulation skills, and building adequate support systems.

The emphasis on safety represented radical departure from therapies pushing rapid trauma processing. Herman warned against premature exposure to traumatic memories, which can retraumatize rather than heal. Survivors need time developing skills for managing overwhelming emotions before confronting their worst experiences.

During this stage, survivors learn recognizing triggers, developing grounding techniques, and building capacity for self-care. Therapists help clients establish predictable routines, identify supportive relationships, and create plans for managing crises. For survivors still in danger—whether from abusive partners, unsafe housing, or other threats—establishing external safety may require practical interventions like shelter, legal advocacy, or protective orders.

Stage Two: Remembrance and Mourning

Once adequate safety and stabilization are achieved, survivors can begin the painful work of remembering and processing traumatic experiences. This stage involves reconstructing trauma narrative, understanding its meaning, and mourning what was lost.

Herman emphasized this work must be done at survivor’s pace, with therapist providing supportive, non-judgmental presence. The goal is not forced remembering but gradually integrating fragmented, dissociated memories into coherent life story. Survivors move from being haunted by uncontrollable flashbacks to having narrative control over their experiences.

This stage involves what Herman called “testimony”—the detailed recounting of traumatic experiences in safe, supportive context. By bearing witness to survivors’ experiences without turning away, therapists help transform unspeakable horror into speakable reality. This testimonial process, Herman argued, serves both personal healing and larger social justice by breaking silence surrounding abuse and violence.

The mourning component addresses losses trauma created: lost innocence, lost trust, lost years of development, lost relationships, lost sense of safety in the world. Herman recognized survivors must grieve these losses before moving forward, and grief work requires time and support.

Stage Three: Reconnection

The final stage involves survivors reconnecting with themselves and world in new ways. Having processed traumatic experiences and mourned losses, survivors can now focus on building meaningful future. This includes developing new relationships, pursuing goals and interests, finding meaning beyond survival, and sometimes engaging in social action or advocacy.

Herman noted many trauma survivors find purpose in helping others who have endured similar experiences. This “survivor mission”—whether through peer support, advocacy, or professional work in trauma field—can provide powerful sense of meaning while contributing to broader social healing.

Reconnection also involves developing new relationship with oneself. Survivors who internalized shame and self-blame during victimization must develop self-compassion and self-acceptance. They reclaim agency over their lives, making choices based on their own values rather than trauma-driven reactivity.

Complex PTSD: Naming the Unnamable

While Trauma and Recovery outlined recovery stages, Herman’s proposal for new diagnostic category proved equally influential. She argued the existing PTSD diagnosis, based primarily on combat veterans’ experiences, inadequately captured psychological impact of prolonged, repeated trauma—particularly when victims cannot escape, as in childhood abuse, domestic violence, or captivity.

Herman proposed “Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” or “C-PTSD” to describe the distinct syndrome resulting from chronic traumatization. In addition to classic PTSD symptoms (intrusion, avoidance, hyperarousal), complex trauma survivors exhibited: fundamental alterations in affect regulation, consciousness, self-perception, perpetrator perception, relationships with others, and systems of meaning.

These individuals struggled with emotional regulation, swinging between emotional numbing and overwhelming affect. They experienced dissociative symptoms—depersonalization, derealization, amnesia—more severely than simple PTSD patients. Their self-concept fractured, characterized by pervasive shame, guilt, and sense of being permanently damaged. They often maintained distorted perceptions of perpetrators, whether idealization, gratitude, or complete preoccupation.

Relationships became profoundly difficult, marked by isolation, distrust, and difficulty maintaining intimate connections. Previously held beliefs and meaning systems—about God, justice, order in universe—collapsed, leaving existential despair. These symptoms reflected not mere symptom addition but qualitative transformation of personality structure itself.

Herman’s complex PTSD concept provided new language for what clinicians had observed but lacked adequate framework to describe. It explained why childhood abuse survivors often received multiple diagnoses—borderline personality disorder, dissociative identity disorder, depression, anxiety disorders—that obscured their shared traumatic origin. It illuminated how domestic violence created deep personality changes beyond discrete traumatic incidents.

The proposal sparked debate. Some argued it unnecessarily complicated PTSD diagnosis. Others worried it pathologized understandable responses to prolonged victimization. But many clinicians and researchers recognized Herman had identified real phenomenon requiring recognition.

In 2018, the World Health Organization included Complex PTSD in the ICD-11, their international classification of diseases. The diagnosis requires PTSD core symptoms plus “disturbances in self-organization” including affect dysregulation, negative self-concept, and relational disturbances. This represented major validation of Herman’s decades-earlier insight, though American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 has not yet followed suit.

The Social Context of Trauma

Throughout her work, Herman insisted trauma cannot be understood purely as individual psychological phenomenon. She argued trauma both reflects and perpetuates existing power structures—particularly patriarchy, which enables widespread violence against women and children.

Herman noted domestic violence and childhood sexual abuse remained largely invisible because they occurred in private, protected by family privacy norms. When victims came forward, they faced systematic disbelief and blame. Legal systems, medical institutions, and mental health professions often minimized or dismissed their experiences.

This social blindness, Herman argued, was not accidental but served existing power structures. Acknowledging widespread violence against women and children would require confronting how supposedly normal families harbor exploitation and abuse. It would demand seeing respected community members as perpetrators rather than victims’ fabrications.

Recovery, therefore, must include not just individual healing but social acknowledgment and justice. Survivors need their experiences validated, their suffering recognized, and perpetrators held accountable. Without this broader social response, individual therapy’s gains remain fragile.

Herman’s analysis connected personal trauma to political realities. She showed how trauma study historically advanced during periods of social upheaval—after wars, during social movements—when society briefly faced violence it usually denies. Understanding trauma requires political consciousness about power, oppression, and resistance.

Influence on Trauma Treatment

Herman’s three-stage model reshaped trauma therapy across therapeutic orientations. Trauma-focused treatments including Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), Prolonged Exposure, and Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy incorporated her emphasis on safety and stabilization before memory processing.

Newer modalities including Internal Family Systems and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy built on her recognition that trauma fragments personality and requires gentle, paced integration. Somatic therapies like Somatic Experiencing reflected her understanding that trauma lodges in body and requires body-based interventions.

Herman’s work influenced how therapists conceptualize therapeutic relationship in trauma work. She emphasized therapists must bear witness without overwhelming or abandoning clients, maintaining steady presence through difficult material. She warned against assuming expert stance that disempowers survivors, instead advocating collaborative relationships respecting clients’ autonomy and wisdom about their own healing.

Her recognition of vicarious traumatization—how trauma work affects therapists’ own psychological well-being—prompted attention to therapist self-care and supervision. She normalized therapists’ emotional responses to trauma material while emphasizing necessity of professional support.

Contributions to Domestic Violence Understanding

Herman’s trauma framework revolutionized domestic violence understanding. Previously viewed primarily through criminal justice or family systems lenses, domestic violence came to be understood as trauma-inducing pattern of coercive control producing complex PTSD symptoms.

She helped clinicians recognize domestic violence creates traumatic bonding between victims and abusers, explaining why victims often struggle leaving dangerous relationships. The combination of intermittent reinforcement, isolation, and terror creates powerful psychological bonds that rational arguments about safety cannot easily overcome.

Herman’s work influenced domestic violence advocacy by emphasizing safety planning, trauma-informed legal advocacy, and long-term support beyond immediate crisis intervention. Domestic violence shelters and programs increasingly incorporated trauma treatment principles, recognizing leaving abuser represents only first step in longer recovery journey.

Childhood Trauma and Development

Herman’s work contributed to growing understanding of childhood trauma’s developmental impact. She showed childhood abuse disrupts normal development across domains: attachment, emotional regulation, identity formation, and capacity for healthy relationships. The younger the victim and longer the abuse, the more profound the developmental distortions.

This insight prompted new attention to complex trauma in children and adolescents. Programs like The National Child Traumatic Stress Network developed screening tools, evidence-based treatments, and training programs addressing childhood complex trauma. Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up, Child-Parent Psychotherapy, and other interventions targeted early relational trauma.

Herman’s work supported growing recognition that many adult mental health problems—including substance abuse, eating disorders, self-harm, and personality disorders—often represent unrecognized complex trauma sequelae. This shifted treatment focus from symptom management toward addressing underlying traumatic origins.

Feminist Scholarship and Activism

Herman’s work represented intersection of rigorous scholarship and feminist activism. She demonstrated how scientific research could serve social justice without compromising intellectual integrity. Her documentation of violence against women provided empirical foundation for feminist arguments about patriarchal violence while remaining accessible to mainstream mental health professionals.

She helped bridge divide between feminist grassroots activism and academic psychiatry, each traditionally suspicious of the other. Feminist activists sometimes viewed psychiatry as pathologizing women’s reasonable responses to oppression. Academic psychiatrists often dismissed feminist perspectives as political rather than scientific. Herman showed these perspectives could be integrated—that understanding trauma required both political consciousness and clinical expertise.

Her work influenced violence against women advocacy globally. International human rights organizations, UN agencies, and domestic violence programs worldwide incorporated her framework. Her recognition that political torture and domestic abuse produced similar psychological effects strengthened arguments that domestic violence constitutes human rights violation requiring state intervention and prevention.

Limitations and Criticisms

Herman’s work, while influential, faced legitimate criticisms. Some argued her three-stage model oversimplified recovery’s nonlinear reality. Survivors don’t move neatly from stage to stage but cycle back repeatedly, work on multiple stages simultaneously, or never fully reach reconnection stage.

Others questioned whether therapy should emphasize extensive memory work, particularly given research on memory’s malleability and false memories. Some survivors heal without detailed memory processing, raising questions about stage two’s necessity.

Critics noted Herman’s framework, developed primarily with women survivors of interpersonal violence, might not fully capture experiences of male combat veterans, torture survivors, or those traumatized by accidents, natural disasters, or medical events. Cultural variations in trauma response and healing also require attention beyond Herman’s primarily Western, individualistic framework.

The complex PTSD concept itself remained contentious. Some researchers argued existing diagnoses adequately captured chronic trauma’s effects without requiring new category. Others worried diagnosing complex PTSD might pathologize poverty, oppression, or systemic racism’s effects rather than addressing root causes.

Legacy and Continuing Influence

Despite limitations, Herman’s influence on trauma field remains profound and enduring. Trauma and Recovery continues appearing on required reading lists for mental health professionals decades after publication. Her three-stage model provides foundational framework taught in trauma training programs worldwide.

The complex PTSD concept’s inclusion in ICD-11 represented major professional acknowledgment of her contribution. Research on complex trauma continues expanding, with neuroimaging studies documenting distinct brain changes, genetic research examining epigenetic effects, and treatment studies developing interventions specifically targeting complex trauma symptoms.

Herman’s work contributed to broader cultural trauma awareness. Terms like “triggers,” “retraumatization,” and “trauma-informed care” entered mainstream vocabulary partly through frameworks she articulated. Organizations across sectors—education, criminal justice, child welfare, healthcare—increasingly adopt trauma-informed approaches recognizing trauma’s ubiquity and impact.

Her emphasis on social justice dimensions of trauma influenced trauma-informed care’s expansion beyond clinical settings. Schools, courts, foster care systems, and other institutions now recognize how structural factors create and perpetuate trauma. This spawned movements toward restorative justice, trauma-sensitive schools, and culturally responsive healing practices.

Contemporary Relevance

Herman’s work remains strikingly relevant to contemporary issues. The #MeToo movement, which brought unprecedented attention to sexual harassment and assault, vindicated Herman’s arguments about widespread sexual violence and systemic barriers to disclosure. Her analysis of why victims delay reporting, struggle with memory, and face disbelief helped public understanding of survivors’ experiences.

Recognition of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and their health impacts built directly on Herman’s documentation of childhood trauma’s long-term effects. The ACEs studies showing childhood trauma’s correlation with adult disease, mental illness, and premature death provided empirical support for claims Herman made decades earlier.

Current attention to police brutality, mass incarceration, and systemic racism connects to Herman’s recognition that social structures can be traumatizing. Scholars extending trauma frameworks to understand collective, historical, and intergenerational trauma build on foundation she helped establish. Concepts like “racial trauma” and “historical trauma” apply Herman’s insights to understanding oppression’s psychological impact on entire communities.

The COVID-19 pandemic created new appreciation for Herman’s insights about collective trauma. Mass death, social isolation, economic devastation, and healthcare system collapse produced trauma symptoms at population level. Her framework for understanding how disasters shatter assumptions about safety and predictability helped make sense of widespread psychological distress.

Integration with Neuroscience

Recent neuroscience research provided biological validation for many observations Herman made clinically. Brain imaging studies revealed trauma’s impact on brain structures and functioning: overactive amygdala (fear center), underactive prefrontal cortex (emotional regulation), and disconnection between brain regions responsible for memory, language, and bodily sensation.

Bessel van der Kolk, Herman’s colleague and collaborator, bridged her psychological frameworks with neuroscientific findings in his bestselling The Body Keeps the Score. This integration helped translate Herman’s insights for broader audiences while providing neurobiological explanations for trauma’s effects she had documented.

Research on neuroplasticity—brain’s capacity for change—supported Herman’s optimism about recovery potential. While trauma changes brain structure and function, appropriate interventions can promote healing and restoration of healthier neural patterns. This validated her emphasis on long-term, comprehensive treatment rather than symptom suppression.

Polyvagal theory, developed by Stephen Porges, provided physiological framework for understanding trauma’s impact on nervous system regulation. This complemented Herman’s observations about hypervigilance, emotional numbing, and relationship difficulties, showing how these reflect dysregulated autonomic nervous system.

Therapeutic Modalities Building on Herman’s Work

Herman’s framework enabled emergence of numerous specialized trauma therapies. Brainspotting, developed by David Grand, processes trauma through identifying eye positions connecting to traumatic material. Lifespan Integration, created by Peggy Pace, uses visualization of life timeline to integrate fragmented memories.

These newer approaches incorporated Herman’s insights about pacing trauma work, establishing safety before processing, and recognizing trauma’s impact on sense of self and relationships. They built specialized techniques targeting specific aspects of complex trauma she identified: fragmented identity, dysregulated affect, disrupted relationships.

Trauma therapy’s diversification represented both Herman’s influence and recognition that no single approach works for everyone. Her framework provided foundation allowing multiple therapeutic innovations addressing trauma from different angles while maintaining core principles of safety, witnessing, and reconnection.

Impact on Professional Training

Herman’s work transformed how mental health professionals are trained. Trauma training, once peripheral to graduate education, became central component of counseling, social work, and psychology programs. Courses on trauma assessment, treatment, and prevention now appear in most mental health training curricula.

Professional organizations including International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies and APA Division 56 (Trauma Psychology) developed practice guidelines, certification programs, and continuing education based partly on frameworks Herman established. These organizations promote evidence-based trauma treatment while advocating for trauma survivors.

Herman’s emphasis on therapist self-care and vicarious traumatization influenced professional training to include wellness, boundaries, and burnout prevention. Recognition that trauma work affects clinicians’ wellbeing prompted organizational changes supporting trauma therapists through supervision, peer consultation, and workplace policies prioritizing sustainability.

As trauma field continues evolving, Herman’s fundamental insights remain relevant. Her recognition that trauma fractures basic assumptions about safety, trust, and human connection—and that healing requires re-establishing these foundations—transcends specific treatment modalities. Her insistence on social context, her documentation of power’s role in both creating and obscuring trauma, and her emphasis on bearing witness rather than turning away continue guiding contemporary practice.

New challenges require extending Herman’s frameworks. Technology’s role in facilitating harassment, surveillance, and exploitation creates new trauma forms. Climate change, pandemic, and other global crises produce collective trauma requiring adaptation of individually-focused treatment models. Ongoing struggles for racial justice, LGBTQ+ rights, and other social movements reveal how oppression itself traumatizes, demanding integration of liberation psychology with clinical frameworks.

Yet Herman’s core message—that trauma’s effects, however devastating, need not be permanent; that with appropriate support, safety, and witnessing, recovery is possible; and that individual healing connects to social justice—remains powerfully true. Her life’s work demonstrated that rigorous scholarship, compassionate clinical practice, and social activism can be integrated in service of healing both individuals and communities.

Legacy

Judith Lewis Herman’s contributions to trauma psychology cannot be overstated. Father-Daughter Incest forced acknowledgment of childhood sexual abuse’s prevalence and impact. Trauma and Recovery provided comprehensive framework for understanding trauma across contexts while outlining recovery pathway. Her complex PTSD concept gave language to experiences previously pathologized or dismissed.

Beyond specific contributions, Herman modeled how scholarship can serve justice without sacrificing intellectual rigor. She bridged feminist activism and academic psychiatry, grassroots advocacy and professional expertise. She demonstrated that understanding trauma requires attending to both individual psychology and social context, both clinical symptoms and political realities.

For trauma survivors, Herman’s work offered validation and hope. By documenting their experiences, naming their suffering, and mapping recovery’s path, she provided framework for making sense of seemingly incomprehensible experiences. Her insistence that trauma need not define survivors’ futures, that healing is possible, and that recovery involves not just symptom reduction but transformation and growth has inspired countless individuals on their healing journeys.

For clinicians, Herman’s frameworks continue guiding trauma-informed practice. Her three-stage model, her emphasis on safety and pacing, her recognition of trauma work’s emotional toll, and her respect for survivors’ resilience and wisdom shaped generations of trauma therapists. She taught that effective trauma treatment requires both technical skill and moral commitment—commitment to bearing witness, seeking justice, and standing with those who have survived atrocity.

For society, Herman’s work demands ongoing reckoning with violence, oppression, and trauma’s ubiquity. Her documentation that trauma stems not from individual pathology but from human cruelty and social injustice challenges comforting fictions about safety and order. She showed that addressing trauma requires not just better therapy but better world—one with less violence, more justice, and greater willingness to face difficult truths.

Judith Herman’s legacy lives in every trauma treatment center applying her recovery stages, every training program teaching complex PTSD, every survivor finding language for their experience, and every social movement demanding justice for trauma’s victims. Her work reminds us that trauma study is ultimately about human dignity, social justice, and collective responsibility for creating world where fewer people are traumatized and all survivors have access to healing they deserve.

Additional Recommended Reading

For readers interested in exploring trauma psychology further, these resources complement Herman’s work:

• Bessel van der Kolk: The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma

• Stephen Porges: The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation

• Pat Ogden: Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment

• Peter Levine: Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma and In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness

• Janina Fisher: Healing the Fragmented Selves of Trauma Survivors

• Richard Schwartz: No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model

**More Information on Trauma Treatment**

For Birmingham-area residents and Alabama teletherapy clients seeking trauma treatment, Taproot Therapy Collective offers specialized trauma-focused therapy incorporating these evidence-based approaches:

• EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing)

• Brainspotting

• Somatic Experiencing

• Parts-Based Therapy and Internal Family Systems

• Jungian Therapy and Depth Psychology

• Comprehensive Trauma Treatment

Learn more about alternative approaches to trauma and CPTSD beyond traditional talk therapy, new frontiers in brain-based therapies for trauma, and understanding somatic experiencing as a mind-body approach to healing.

For information on therapists specializing in trauma treatment, visit Taproot Therapy Collective’s therapist directory or learn about Birmingham trauma specialists.

Additional resources exploring the historical and philosophical dimensions of trauma therapy can be found in articles like The Architecture of the Soul and the Machine: A Critical History and Future of Psychotherapy, The Great Shift: Why the Market is Moving from CBT to Somatic and Neuro-Experiential Therapies for Trauma, and The Somatic and Neurological Experience of Brainspotting Therapy.

0 Comments