THE ARCHITECTURE OF AMERICAN MADNESS

Leadership Dynamics, Economic Imperatives, and the Epistemological Crisis of Psychiatric Diagnosis

By Joel Blackstock, LICSW-S

Clinical Director, Taproot Therapy Collective

“The DSM is not a description of nature. It is a description of what American healthcare requires nature to be.”

Contents

- Introduction: The Controversial Bible

- Part I: The Archaeology of a Label — What Is Diagnosis?

- Part II: Military Origins — The DSM Emerges from World War II

- Part III: The Gentlemen’s Club — DSM-I and DSM-II

- Part IV: The Storm Breaks — Anti-Psychiatry and the Crisis of the 1970s

- Part V: The Dopamine Miracle — How Schizophrenia Saved Psychiatry

- Part VI: Spitzer’s Revolution — DSM-III and the Checklist

- Part VII: The Backwards Method and Why It Matters

- Part VIII: The Neoliberal Turn — Reagan, Thatcher, and the Demand for Metrics

- Part IX: The Golden Cage — The RUC and the Death of Talk Therapy

- Part X: The Divorce — When Psychiatry and Therapy Parted Ways

- Part XI: The Conservative Correction — DSM-IV and the False Epidemics

- Part XII: The Collapse — DSM-5 and the NIMH Divorce

- Part XIII: The Reproducibility Crisis — CBT, STAR*D, and Broken Promises

- Part XIV: The Shadow Tradition — Joseph Campbell and the Return of Depth

- Part XV: The “Dopamine Disorder” and the Flattening Problem

- Part XVI: The Roads Not Taken — HiTOP, RDoC, and the Layered Model

- Part XVII: Borderline — A Fossil of a Broken System

- Part XVIII: What Mental Health Actually Is (The Mattering Problem)

- Part XIX: The Paralysis — Where We Are Now

- Conclusion: The Synthesis We’re Waiting For

- Bibliography

The Controversial Bible

Love it or hate it, therapists have to use the DSM. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published by the American Psychiatric Association, functions as the definitive classification system for mental health conditions in the United States. Every diagnosis we give, every insurance claim we file, every treatment plan we justify—all of it flows through the DSM’s categorical architecture. It is, for all practical purposes, the bible of American psychiatry.

And yet, the fact that we have to diagnose under its criteria is one of the most controversial issues I have encountered in the field. Off the record, approximately half of the therapists I’ve spoken with over my career have enormous problems with the document—not with the idea of diagnosis or diagnostic criteria itself, but with the value structure, the operating assumptions, and the contradictions built into the Evidence Based Practice model as it currently exists.

To understand these cross-purpose assumptions, the shifting scope of conceptualizations, and the seeming contradictions of what the DSM has become, we must look at the history of the thing itself and the forces that it has responded to across its development. What emerges from this investigation is not a story of scientific progress, but a chronicle of defensive reactions—a document shaped more by professional insecurity, insurance mandates, and pharmaceutical economics than by the pure pursuit of understanding human suffering.

This is not an argument against diagnosis. It is not an argument against science. It is an argument that we should look for problems with the way we conduct science in order to make it more scientific—and that we should make diagnostic criteria capable of confronting the mental health crisis we are now presented with, rather than serving the profit motives of healthcare corporations and the nonsensical hierarchies of academia.

The history of the DSM from its military origins to the present day is a cautionary tale of how a profession saved itself with a “necessary lie” (operationalism) and then forgot it was lying. What follows is an attempt to trace that history comprehensively, to understand how we arrived at our current impasse, and to sketch what a path forward might look like.

Part I: The Archaeology of a Label — What Is Diagnosis?

The Ancient Problem: When the Gods Made You Mad

Before there were psychiatrists, there were priests. And before there were diagnostic manuals, there were myths.

The ancient Greeks had a word for what we now call mental illness: mania. But mania didn’t mean what we mean by it. When Dionysus drove the women of Thebes to tear King Pentheus limb from limb, that was mania. When Ajax slaughtered a flock of sheep believing them to be his enemies, that was mania. When the Oracle at Delphi spoke in tongues, possessed by Apollo, that too was a kind of divine madness.

The crucial point is this: for the ancients, madness was not a malfunction. It was a communication. The gods were speaking through the afflicted person. The “symptoms” were messages that required interpretation, not suppression. The healer’s job was not to eliminate the madness but to understand what it meant. What did the gods want? What did the person’s soul require?

This is alien to our modern sensibility, but sit with it for a moment. If you believed that hearing voices meant a god was trying to tell you something, your entire approach to treatment would be different. You wouldn’t try to make the voices stop. You’d try to figure out what they were saying. You might fast, or pray, or go on a pilgrimage. The “disorder” would be understood as a crisis of meaning, not a broken neurotransmitter.

I’m not saying the Greeks were right. I’m saying they had a coherent framework that gave suffering a place in the cosmic order. The DSM has no such framework. It just lists symptoms.

The Hippocratic Turn: From Gods to Humors

Around the fifth century BCE, something shifted. The Hippocratic physicians, the founders of Western medicine, started arguing that madness wasn’t divine. It was natural. Specifically, it was a disorder of the four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile.

The famous Hippocratic text On the Sacred Disease (about epilepsy) makes this argument explicitly. The author is furious at people who attribute seizures to the gods. “It is not, in my opinion, any more divine or sacred than other diseases,” he writes, “but has a natural cause.” The cause, he argues, is an excess of phlegm in the brain.

This was revolutionary. By relocating madness from the heavens to the body, the Hippocratics created the conceptual space for medicine. But notice what they kept: the idea that the patient’s condition means something. The humors weren’t just chemicals. They were connected to the seasons, the elements, the temperaments. A melancholic person (too much black bile) wasn’t just sick. They had a particular kind of soul, a particular relationship to the world. The diagnosis told you something about who they were.

The humoral system dominated Western medicine for nearly two thousand years. Galen systematized it in the second century. Medieval physicians refined it. Even into the Renaissance, doctors were still prescribing bloodletting to reduce excess blood, or purgatives to eliminate black bile. The treatments were often useless or harmful, but the framework was coherent. Illness was an imbalance. Health was harmony. The doctor’s job was to restore the patient’s proper relationship to their own nature and to the cosmos.

The Enlightenment Rupture: Mind as Machine

Then came Descartes, and everything fell apart.

Descartes’ famous division of reality into res cogitans (thinking stuff) and res extensa (extended stuff) created a philosophical puzzle that we still haven’t solved. The body was a machine, operating according to mechanical laws. The mind was something else. A ghost in the machine. Immaterial, indivisible, free.

This dualism made modern science possible. By declaring the body to be pure mechanism, Descartes gave permission to dissect it, measure it, experiment on it without worrying about the soul. But it created a massive problem for psychiatry. If the mind is immaterial, how can it be sick? If mental illness is real, where exactly is it located?

The nineteenth century tried various answers. Phrenologists thought mental faculties were located in specific brain regions that you could feel through the skull. Asylum doctors looked for brain lesions in their deceased patients. But the results were disappointing. You could find brain damage in some cases of madness, but not in others. Many conditions that looked like diseases—melancholia, hysteria, neurasthenia—seemed to have no physical basis at all.

This is the dirty secret that haunts psychiatry to this day: we still don’t have biomarkers for most mental disorders. After 150 years of looking, we cannot point to a blood test or a brain scan that definitively diagnoses depression, or anxiety, or PTSD. The DSM knows this. The committees know this. But the whole edifice of “medical model” psychiatry is built on the assumption that such markers exist and will eventually be found. The biomarkers have been “coming soon” since 1980.

Kraepelin and the Birth of the Checklist

The modern psychiatric diagnosis was essentially invented by one man: Emil Kraepelin, a German psychiatrist working in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Kraepelin’s innovation was simple but profound. He stopped trying to find the cause of mental illness and focused instead on the course. He spent decades meticulously observing patients in asylums, tracking their symptoms over time. He noticed that certain clusters of symptoms tended to hang together and follow predictable trajectories. Some patients got sick young, deteriorated steadily, and never recovered. Others had episodes of illness followed by periods of relative health.

From these observations, Kraepelin carved out the two great categories that still structure psychiatry today: dementia praecox (later renamed schizophrenia) and manic-depressive illness (later split into bipolar disorder and major depression). His method was purely descriptive. He didn’t claim to know what caused these conditions or what was happening in the brain. He just described what he saw.

This Kraepelinian approach—describing symptoms without explaining them—is exactly what Robert Spitzer would resurrect in DSM-III. But there’s a crucial difference. Kraepelin spent decades watching patients before he drew any conclusions. He knew his patients intimately. Spitzer’s checklists were designed to make that kind of intimate knowledge unnecessary. You don’t need to know the patient; you just need to count their symptoms.

Freud and the Rebellion Against Labels

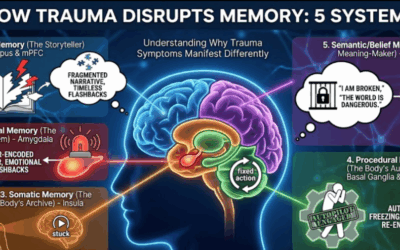

Before Spitzer, before the checklists, there was Freud. And whatever else you want to say about Freud, he understood something that the DSM has forgotten: symptoms are not just problems to be eliminated. They’re solutions to deeper problems. They mean something.

Freud’s great insight—one that has been validated over and over by trauma research, even as his specific theories have been abandoned—is that psychological symptoms often represent the return of experiences that couldn’t be processed when they occurred. The hysterical paralysis isn’t random; it’s connected to a memory, a conflict, a wish that couldn’t be acknowledged. The obsessive ritual isn’t meaningless; it’s an attempt to bind anxiety that would otherwise be overwhelming.

In this framework, diagnosis is less important than understanding. What matters is not which box the patient fits into, but what their particular symptoms mean in the context of their particular life. Two patients with identical symptoms might have completely different dynamics. One might be depressed because of unresolved grief; another might be depressed because of suppressed rage; a third might be depressed because their entire way of understanding themselves has collapsed. The checklist sees three cases of “Major Depressive Disorder.” Freud would see three entirely different problems requiring three entirely different approaches.

This is what the DSM threw away. In the name of reliability—getting doctors to agree—it sacrificed meaning. And in doing so, it made itself scientifically useless for finding cures.

Part II: Military Origins — The DSM Emerges from World War II

Technical Bulletin Medical 203

Here’s something that should be a scandal but somehow isn’t: the DSM didn’t emerge from hospitals or research universities. It emerged from the U.S. Army’s need to process soldiers during World War II.

The military had a problem. Millions of young men were being drafted, and a significant percentage of them were cracking under the stress of combat. The Army needed to figure out who was fit for duty, who should be discharged, and who was entitled to a pension. They couldn’t have 500 different psychiatrists writing long essays about each soldier’s childhood. They needed codes. They needed to turn complex human beings into standardized units of data that could be processed by a clerk in Washington.

The solution was Technical Bulletin Medical 203, issued by the War Department in 1943. This document created a standardized nomenclature for psychiatric conditions—the first time American psychiatry had anything like a common language. After the war, the Veterans Administration adopted it. And when the American Psychiatric Association decided to create a unified diagnostic manual in 1952, they essentially copied Medical 203 with minor modifications.

This is the origin story of the DSM. Not a hospital. Not a laboratory. A military bureaucracy trying to manage a logistics problem.

The Logistics of Madness

Understanding this origin is crucial because it explains so much about what the DSM is and what it isn’t. The military didn’t need to understand why soldiers were suffering. They didn’t need to cure anyone. They needed to sort people into categories for administrative purposes: fit for duty, unfit for duty, entitled to disability payments, not entitled.

This administrative function has never left the DSM. The manual exists not primarily to advance scientific understanding or improve clinical care, but to provide standardized codes for bureaucratic purposes: insurance billing, disability determinations, research funding, legal proceedings. The science was always secondary to the administration.

Part III: The Gentlemen’s Club — DSM-I and DSM-II

The Dynamic Era (1952-1980)

The first edition of the DSM, published in 1952, and its successor, DSM-II (1968), were fundamentally different documents from the manuals used today. They were products of their time, heavily influenced by the psychodynamic and psychoanalytic theories that dominated American psychiatry in the post-World War II era.

In this “dynamic” paradigm, mental disorders were not viewed as discrete, static disease entities. Instead, they were conceptualized as “reactions”—fluid, dynamic processes resulting from the interplay between an individual’s internal personality structure and environmental stressors. The nomenclature of DSM-I explicitly used the term “reaction” for many conditions (e.g., “Schizophrenic reaction,” “Depressive reaction”), reflecting the belief that symptoms were a manifestation of the patient’s struggle to adapt to psychological conflict.

This model was inherently dimensional in its philosophy. It viewed pathology as a matter of degree rather than kind. A “neurosis” was not a separate species of existence but an exaggeration of normal defense mechanisms. The diagnosis required a deep, interpretive understanding of the patient’s life history, unconscious conflicts, and personality dynamics.

Inside the DSM-I Committee: The Wartime General

The biggest controversy inside the DSM-I (1952) committee was that the people writing the book didn’t actually believe in diagnosis. The dominant figure was the spirit of Adolf Meyer, the “Dean of American Psychiatry.” Meyer hated labels. He believed every patient was a unique biopsychosocial story.

On one side, you had the Census Bureau types who wanted distinct boxes (“Schizophrenia,” “Manic Depression”) to count people. On the other side, you had the Meyerians who argued that putting a label on a patient was an insult to their complexity. The committee solved this by adding the word “Reaction” to almost everything. You didn’t have “Schizophrenia” (a static disease). You had “Schizophrenic Reaction” (a temporary response to life). This was a philosophical coup.

But there was also a power play. The Chair of the DSM-I committee wasn’t just a doctor; he was Brigadier General William Menninger. He had run psychiatry for the US Army during WWII and developed Medical 203. He essentially marched into the civilian committee and said, “This is what the Army uses. Adopt it.” The civilian academics—East Coast elites—resented the military encroaching on their turf. But Menninger won because he had the prestige of the war victory. The DSM-I is largely a copy-paste of the Army’s “Medical 203.” The controversy was effectively Military Pragmatism conquering Civilian Theory.

The Imperial Unconscious of DSM-I

If you read the DSM-I with fresh eyes, you’ll notice something uncomfortable: it’s saturated with the assumptions of mid-century American empire.

Start with homosexuality. In DSM-I, it was listed under “Sociopathic Personality Disturbance,” grouped with antisocial behavior and sexual deviations. This wasn’t just ignorance; it was ideology. Gay people were defined as having no moral compass, as fundamentally disordered in their relationship to society. The diagnosis served a function: it justified denying gay people security clearances, government jobs, and basic civil rights.

Or consider the treatment of women. “Hysteria,” a diagnosis applied almost exclusively to women, was still very much alive. The term comes from the Greek word for uterus; the ancient assumption was that women’s mental disturbances came from their wandering wombs. By 1952, nobody believed that literally anymore, but the diagnosis persisted, and it was still gendered. Women who didn’t fit the expected mold—who were too emotional, too sexual, too independent—could be pathologized.

Or consider the implicit racial assumptions. The early DSM had nothing to say about how racism might affect mental health. It couldn’t even conceive of the question. The patient was always an isolated individual with an internal disorder. The social environment was backdrop, not cause. If a Black man in Jim Crow Alabama was depressed, that was his neurochemistry, not his circumstances.

DSM-II and the International Brawl

By the time of the DSM-II (1968), the committee was fighting a new war: Globalism. The World Health Organization had just published the ICD-8. They told the Americans: “Stop using your weird Freudian terms. Align with the rest of the world.”

Inside the committee, there was a split. The Internationalists wanted to adopt the European/ICD terms, which were more biological and Kraepelinian. The American Freudians refused to give up terms like “Neurosis” and “Hysteria.” They argued that European psychiatry was “superficial” because it ignored the unconscious mind.

The committee spent months arguing over the word “Hysteria.” The Europeans had banned it, calling it antiquated. The Americans insisted on keeping it. They kept “Hysterical Neurosis” in the DSM-II to appease the American analysts, making the US look scientifically backward compared to Europe.

| Feature | DSM-I (1952) | DSM-II (1968) |

|---|---|---|

| Paradigm | Psychodynamic “Reaction” Model | Fractured Psychoanalytic |

| Origin | Military (Medical 203) | WHO Pressure / ICD-8 Alignment |

| Diagnostic Logic | Interpretive / Narrative | Narrative with Slight Standardization |

| Reliability | Low (Subjective Interpretation) | Low (US-UK Project Exposed Problems) |

Part IV: The Storm Breaks — Anti-Psychiatry and the Crisis of the 1970s

R.D. Laing and the Intelligibility of Madness

By the 1960s, the insularity of psychiatry was shattered. The cultural revolution of the decade brought all forms of authority into question, and the psychiatrist—as the arbiter of normality—became a prime target.

R.D. Laing, a Scottish psychiatrist, struck at the heart of the medical model’s assumption that mental illness was a “breakdown” of function. In seminal works like The Divided Self (1960), Laing argued that what looked like “madness” was often a sane, intelligible strategy for surviving an unlivable situation.

Laing posited that the “schizophrenic” was not a broken machine but an existential voyager. He suggested that the bizarre speech and behavior of the psychotic were coded communications about the “double binds” and mystifications imposed by their families and society. “The divided self,” Laing wrote, was a protective reaction to a world that demanded a false self.

Thomas Szasz and the Myth of Mental Illness

While Laing attacked from the left, Thomas Szasz attacked from the right. In The Myth of Mental Illness (1961), Szasz dismantled the logical coherence of the psychiatric enterprise. He argued that the concept of “mental illness” was a category error, a semantic trap.

Szasz contended that psychiatry was a pseudoscience used by the state to police social deviance. By labeling behaviors as “illnesses,” society avoided the difficult ethical work of dealing with conflict. The “mental illness” label allowed the state to incarcerate innocent people (involuntary commitment) without the due process of the criminal justice system.

Rosenhan and the ‘Thud’ Experiment

If Laing and Szasz provided the theoretical indictment of psychiatry, David Rosenhan provided the empirical conviction. His 1973 study, “On Being Sane in Insane Places,” was a masterstroke of experimental sociology that targeted the “subjective intuition” of the clinician.

Rosenhan recruited eight “pseudopatients”—sane individuals with no history of mental illness—to present to hospitals complaining of hearing voices saying only three words: “empty,” “hollow,” and “thud.” Beyond this single fabrication, they were instructed to behave completely normally. All were admitted. All were diagnosed with serious mental illness. Once inside, they acted normally, yet the staff—blinded by the diagnostic label—reinterpreted their normal behavior as pathological.

Rosenhan’s conclusion was devastating: “It is clear that we cannot distinguish the sane from the insane in psychiatric hospitals.” He had proven that the “clinical gaze”—the intuitive ability of the expert to see the illness in the patient—was a myth. The context (the “insane place”) overpowered the reality of the person.

Part V: The Dopamine Miracle — How Schizophrenia Saved Psychiatry

The Legitimizing Power of Antipsychotics

Here’s the irony that nobody talks about: what actually saved psychiatry wasn’t the checklists. It was schizophrenia.

By the early 1970s, psychiatry was in crisis. The anti-psychiatry movement had devastated public trust. Rosenhan had humiliated the profession. Insurance companies were questioning why they should pay for treatments that seemed indistinguishable from philosophy. The field was on the verge of losing its medical legitimacy entirely.

And then the antipsychotics started working. Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) had been introduced in the 1950s, but it took time for its implications to sink in. By the 1970s, psychiatrists could do something dramatic with severe psychotic disorders. You could take a person who was homeless, hallucinating, completely unable to function, give them a pill, and watch them stabilize. This was visible. This was measurable. This was undeniable.

The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia emerged from this clinical success. It gave psychiatry something that looked like real medicine: a biological theory, a drug that targeted that biology, and clinical results that seemed to validate the whole enterprise.

The Legitimization Cascade

The success with schizophrenia and severe bipolar disorder became psychiatry’s trump card. It legitimized everything else. The logic went something like this: we can treat schizophrenia with medication that affects brain chemistry. Therefore, mental illnesses are brain diseases. Therefore, all our diagnostic categories must correspond to real biological entities. Therefore, the DSM is scientific.

But notice the leap. The fact that antipsychotics help with schizophrenia doesn’t prove that “major depressive disorder” or “generalized anxiety disorder” are also biological entities in the same way. The success with the dopamine disorders was used to justify the entire medical model, even for conditions where the evidence was much weaker. This is what saved psychiatry in the 1970s. Not the checklists. Not scientific rigor. The fact that you could show a skeptic a psychotic patient, give them a pill, and demonstrate improvement.

Part VI: Spitzer’s Revolution — DSM-III and the Checklist

Robert Spitzer: The Outsider

Robert Spitzer was the singularity at the center of the DSM-III universe. A professor at Columbia University, he was described by colleagues as a brilliant but socially awkward “outsider.” He had undergone psychoanalytic training, but he never fit the mold of the empathetic, interpretative analyst. Spitzer was uncomfortable with ambiguity. In the hazy world of 1970s psychiatry, he was a man obsessed with categorization and data.

The APA gave him the job because he had proven he could navigate political minefields. He had brokered the homosexuality compromise in 1973, removing it as a disorder. He had shown he could rewrite the bible without destroying the organization. Now they needed someone who could save the profession itself.

The ‘Atheoretical’ Compromise

Spitzer’s strategic genius was the decision to make the DSM-III “atheoretical.” The problem was that the field was fractured. Psychoanalysts believed depression was caused by anger turned inward; biological psychiatrists believed it was a chemical imbalance. They could not agree on cause (etiology).

Spitzer’s reaction: propose a manual that ignored cause entirely. It would focus solely on description. It didn’t matter why the patient was depressed; it only mattered that they had “depressed mood, insomnia, weight loss, and fatigue for 2 weeks.” This was a diplomatic masterstroke. It allowed Freudians and biological psychiatrists to use the same codes. But it was also a philosophical retreat. By abandoning the “why,” the DSM stripped diagnosis of its meaning. It became a taxonomy of surfaces.

The Typewriter Parties

This is where it gets weird. Spitzer would gather experts in a room—sometimes at Columbia, sometimes at his house—and essentially hold symptom-shouting contests. Imagine the scene. A dozen psychiatrists who have been arguing about “depression” for thirty years. Spitzer at his typewriter. He throws out a symptom: “Feeling worthless.”

“Okay, if the patient feels worthless on Tuesday but not Wednesday, does that count?” Someone says yes. Someone says no. They argue. “How many weeks of sadness before it’s Major Depression? Two? Four? Six?” Shouting. Horse-trading. Finally someone yells, “Two weeks!” and Spitzer types it before anyone can object.

This was not science. This was politics. It was a feat of consensus-building, a way of getting stubborn experts to agree on something, anything, so that the paperwork could be standardized. Spitzer was chasing a statistic called Kappa (a measure of how often two raters agree on a diagnosis), and he realized the only way to get high Kappa was to remove judgment from the equation.

Part VII: The Backwards Method and Why It Matters

How Science Should Work

Here’s the thing nobody talks about: Spitzer’s method was completely backwards from how science is supposed to work. The scientific ideal would be to gather data first. You would observe thousands of patients, record all their symptoms, and use statistical methods (factor analysis) to see which symptoms cluster together. Maybe you’d discover that what everyone calls “depression” is actually three different conditions that need different names. Maybe you’d find that “anxiety” and “depression” overlap so much they shouldn’t be separate categories.

This approach has a name: factor analysis. It’s what the HiTOP model does today. And if Spitzer had done it this way, the DSM would look completely different.

Why Spitzer Worked Backwards

But Spitzer couldn’t do it this way. Why? Because the establishment already existed. Psychiatrists had been using terms like “schizophrenia” and “depression” and “anxiety” for decades. They had built their careers around these categories. Their textbooks were organized around them. If Spitzer had announced that factor analysis revealed “schizophrenia” wasn’t real, the profession would have rejected his book entirely.

So Spitzer worked backwards. He started with the names—the categories that psychiatrists already believed in—and then tried to get them to agree on what symptoms defined each name. He didn’t find the symptoms and build the house; he had the house (the label) and looked for bricks (symptoms) to build the walls.

Part VIII: The Neoliberal Turn — Reagan, Thatcher, and the Demand for Metrics

The Accountability Revolution

By the 1980s, the Reagan and Thatcher revolutions were in full force. The neoliberal idea that government needed to justify all of its expenditures with rigorous accountability and assessment became the dominant paradigm. This meant objective metrics to see how hospitals, healthcare, and psychotherapists were performing.

This was the beginning of a profound shift in mental health toward Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), which was perfectly suited to the new accountability environment. It was manualized, time-limited, and measurable. CBT produced results that looked good on paper, fitting the new administrative metrics. The psychodynamic and humanistic therapies that had dominated the field couldn’t compete in this environment. How do you put a number on “working through childhood trauma”?

Part IX: The Golden Cage — The RUC and the Death of Talk Therapy

The Cartel in the Basement

While Spitzer was having his typewriter parties, a much quieter, deadlier revolution was happening in the basement of American medicine. This revolution wasn’t about philosophy or diagnosis. It was about money. And unlike the DSM, which was public and controversial, this revolution happened in a room almost nobody knew existed.

It’s called the RUC: The AMA/Specialty Society Relative Value Scale Update Committee. If you’ve never heard of it, that’s by design. It is a private committee run by the American Medical Association that essentially tells the federal government how much Medicare should pay for every medical procedure. Because private insurance companies almost universally follow Medicare’s lead, this committee effectively sets the price for all healthcare in America.

The RUC operates under a unique regulatory shelter that allows it to function as a legal cartel. If independent doctors did this, they would go to jail for price-fixing. But because the RUC technically only “advises” the government (advice which is accepted 90% of the time), it is protected.

The Chilling Effect: Procedures Over People

The RUC is dominated by specialists who perform procedures—surgeons, radiologists, anesthesiologists. Their bias is structural and overwhelming: they value “doing things to people” (cutting, scanning, injecting) far more highly than “talking to people” (diagnosing, counseling, managing complex chronic conditions).

In the late 1980s and early 90s, psychiatry pivoted. The psychiatric representatives on the RUC realized they couldn’t compete with the proceduralists if they emphasized talk therapy. Talk therapy looks “easy” to a surgeon. It’s “just talking.” So, psychiatry emphasized the one thing they could do that psychologists and social workers couldn’t: prescribe medication. They argued that “medication management” was a complex, high-risk medical procedure.

The Economic Straitjacket

The result was catastrophic for the soul of the profession. The RUC assigned high relative value units (RVUs) to brief medication checks (CPT code 99213 or 99214) and comparatively low values to the psychotherapy codes. The math became brutal. A psychiatrist could see three or four patients in an hour for medication checks, billing significantly more in total than they could for seeing one patient for an hour of therapy.

This created a chilling effect that froze the entire profession. Even psychiatrists who wanted to do therapy—who believed in it, who were trained in it—couldn’t afford to. The “invisible hand” of the RUC pushed them inexorably toward the 15-minute med check.

This is why the “checklist” model of the DSM became not just an intellectual preference but an economic survival strategy. If you only have 15 minutes with a patient, you cannot do a dynamic formulation. You can only run down a list of symptoms, check the boxes, and write a prescription. The DSM provided the perfect administrative tool for the assembly-line medicine the RUC demanded.

Part X: The Divorce — When Psychiatry and Therapy Parted Ways

They Used to Share the Same Room

Here’s something that gets overlooked in every analysis of the DSM: psychiatrists don’t do therapy anymore. Read Irvin Yalom—who was the gateway drug that brought a lot of people into the profession—and you’ll find a psychiatrist who spent hours with patients exploring their fears, their histories, their dreams. He was the prescriber and the therapist in the same relationship. He knew his patients deeply before he ever wrote a prescription.

Try to find a psychiatrist like that today. If you find one, they’re either independently wealthy or pushing 80. The economics of the profession make it impossible. So psychiatry split. The prescribing authority stayed with psychiatrists. The therapeutic relationship went to psychologists, social workers, counselors. The person who knows you deeply is not the person who controls your medication.

This disconnect matters. When you separate diagnosis from relationship, you get checklist diagnosis. Of course you do. The psychiatrist doesn’t have time to understand your life. They have 15 minutes to count your symptoms and adjust your meds. The DSM is perfectly designed for this assembly-line model of care. It’s a tool for people who don’t know their patients.

Part XI: The Conservative Correction — DSM-IV and the False Epidemics

Allen Frances and the DSM-IV

Allen Frances, who chaired the DSM-IV task force, explicitly did not want to be Robert Spitzer. Spitzer’s revolution had been explosive. Frances wanted stabilization. His mantra was “no new diagnoses without hard data.” He ran a conservative, committee-heavy process designed to prevent the reckless expansion of the manual.

And yet, despite his caution, DSM-IV triggered three massive epidemics that Frances has spent the rest of his career apologizing for: ADHD, Bipolar II, and Autism.

How did this happen? The committees loosened criteria slightly—not dramatically, just slightly—and the results cascaded beyond anything they anticipated.

| Epidemic | Mechanism of Inflation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| ADHD | Diagnosis allowed based on teacher reports about classroom behavior | 10% of US children diagnosed; massive stimulant prescriptions |

| Bipolar II | Loosening of criteria for “hypomania” captured ordinary mood swings | Patients shifted from antidepressants to more profitable mood stabilizers |

| Autism/Asperger’s | Introduction of Asperger’s expanded spectrum to high-functioning eccentricity | Rates went from 1 in 2,500 to 1 in 36 |

Frances learned a bitter lesson: bureaucratic methodologies are inherently inflationary. Once a checklist exists, the pressure from patients (seeking validation), parents (seeking school services), and pharmaceutical companies (seeking customers) forces the gate open.

Part XII: The Collapse — DSM-5 and the NIMH Divorce

The Bombshell: April 29, 2013

Two weeks before the DSM-5 was scheduled to launch, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) dropped a bomb that should have been front-page news. Thomas Insel, the Director of the NIMH, published a blog post titled “Transforming Diagnosis.” In it, he declared that the NIMH—the largest funder of mental health research in the world—would be “re-orienting its research away from DSM categories.”

This was a stunning vote of no confidence. It was a preemptive strike. Insel didn’t wait for the book to come out and fail; he killed its scientific credibility before it hit the shelves. He wrote: “While DSM has been described as a ‘Bible’ for the field, it is, at best, a dictionary… The weakness is its lack of validity.”

This was an acknowledgement of a massive failure. The DSM-5 task force had spent 14 years and $25 million promising that they would find the “biomarkers”—the genetic or neurological proof—that these disorders were real diseases. They failed. They found nothing. No blood test for depression. No brain scan for autism. The new manual was just another re-shuffling of the same old symptom checklists.

Moving the Goalposts on Reliability

The failure was so complete that the task force had to change the rules of their own game. In the field trials for DSM-5 (where they tested if doctors could agree on a diagnosis), the results were abysmal. For Major Depressive Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder, the Kappa scores (a statistical measure of agreement) were barely better than chance. In any other science, this would mean the experiment failed. Instead, the DSM leadership simply lowered the standard for what counted as “good” reliability. They redefined failure as success so they could publish the book on time.

Part XIII: The Reproducibility Crisis — CBT, STAR*D, and Broken Promises

The Gold Standard Tarnishes

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) was supposed to be the answer. It was manualized, measurable, time-limited—everything the accountability revolution demanded. For decades, it was considered the gold standard of evidence-based psychotherapy.

But the evidence is crumbling. The reproducibility crisis that has swept through psychology has not spared CBT. Studies that seemed to show clear effects are failing to replicate. Meta-analyses show that effect sizes have been declining over time—as methodology has improved and industry funding has decreased, the apparent benefits of CBT have shrunk.

The STAR*D Scandal

The STAR*D study—the most comprehensive taxpayer-funded study of depression treatment—claimed that 67% of patients would achieve remission through the recommended protocol of CBT and medication cycling. A forensic reanalysis revealed the true sustained recovery rate was 2.7%.

This should have been a scandal. It should have prompted a complete reassessment of how we treat depression. Instead, it was largely ignored. The old treatment guidelines stayed in place. The market is now shifting toward somatic and parts-based interventions, approaches that were discarded in the 1970s but are now returning because clinicians discovered—independently and repeatedly—that they actually help people.

Part XIV: The Shadow Tradition — Joseph Campbell and the Return of Depth

The Hero’s Journey in a Checklist World

Something remarkable happened in American culture at almost exactly the moment psychiatry was abandoning narrative. A scholar named Joseph Campbell became famous. His work on mythology and the Hero’s Journey (based on Jung) exploded into popular culture through Star Wars and Bill Moyers’ interviews.

Why did Campbell resonate so powerfully at exactly this moment? Because psychiatry had stopped providing meaning. The DSM-III stripped the “why” out of diagnosis. Campbell offered something different. He offered a framework for understanding life as a journey, suffering as initiation, crisis as the call to adventure. In Campbell’s telling, the dark night of the soul wasn’t a disorder to be medicated away. It was a necessary phase of transformation.

The Shadow Tradition: Experiential Therapy Takes Root

This cultural wave of narrative and meaning didn’t just stay in Hollywood. It seeped into the practice of therapy, creating a “Shadow Tradition” of somatic and experiential models that flourished outside the academic mainstream. While the DSM was flattening patients into checklists, therapists were discovering that healing often required somatic experiencing and parts work. The concepts of Jung and Campbell became the unacknowledged DNA of models like:

- Internal Family Systems (IFS): Richard Schwartz’s model of “parts” (Managers, Firefighters, Exiles) is essentially a systematic way of doing inner child work and shadow integration. It treats the psyche as a multiplicity of characters, much like a mythic story, rather than a singular broken machine.

- Gestalt Therapy: Fritz Perls focused on the “here and now” experience and the integration of fragmented parts of the self. The “empty chair” technique is a way of dialoguing with internal archetypes.

- AEDP (Accelerated Experiential Dynamic Psychotherapy): Diana Fosha’s model explicitly uses the concept of “transformance”—a drive toward healing and growth that mirrors Campbell’s heroic drive—to undo aloneness and process emotion.

These models are now exploding in popularity because they work. They speak to the human need for narrative and integration that the DSM ignores. They treat the patient as a protagonist in a meaningful struggle, not a carrier of a diagnostic code.

Part XV: The “Dopamine Disorder” and the Flattening Problem

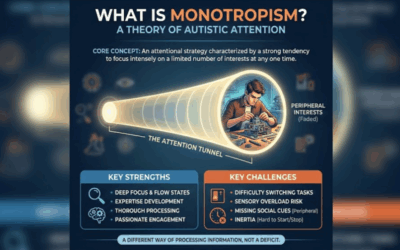

One of the most profound failures of the checklist model is its “flattening” effect. The DSM treats all diagnoses as fundamentally the same kind of thing—a collection of symptoms that, if present, equal a disorder.

But clinicians know that some things are not like the others. Specifically, the “dopamine disorders”—Schizophrenia, Bipolar I, and Schizoaffective Disorder—share a biological reality that is fundamentally different from a personality disorder or a situational depression.

We know these disorders share similar neurological routes. We know they respond consistently to the same classes of medication (antipsychotics and mood stabilizers). And perhaps most importantly, we know that therapists have a hard time telling them apart.

When a patient is in the throes of a manic episode with psychotic features, they look remarkably like a patient with schizoaffective disorder. A patient with schizophrenia who has prominent mood symptoms blurs into bipolar territory. The DSM forces us to draw sharp lines between these conditions—you are either Bipolar OR Schizophrenic—but clinical reality is fuzzy.

This fuzziness is a signal. The fact that patients have a hard time understanding the difference, and therapists have a hard time telling them apart, should tell us something: these are likely expressions of the same underlying biological vulnerability. They are variations on a theme, not separate species. By “flattening” these biologically robust conditions into the same checklist format as “Adjustment Disorder,” the DSM obscures the reality of both.

Part XVI: The Roads Not Taken — HiTOP, RDoC, and the Layered Model

The Scientific Ideal: Factor Analysis

The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) is the model Spitzer should have built. It uses factor analysis to see how symptoms actually cluster. HiTOP reveals that mental illness isn’t a bunch of separate boxes; it’s a hierarchy. It solves the comorbidity problem naturally. A patient with “depression” and “anxiety” doesn’t have two diseases; they have a high score on the “Internalizing” spectrum.

The NIMH Bias: Brains Over Minds

So why doesn’t the NIMH fund HiTOP? Why are they still pouring money into the failed RDoC project? Because the NIMH has a bias. It is a bias toward biological reductionism. The NIMH wants to be a “brain institute,” not a “mind institute.” They believe that the only “real” science is wet science—neurotransmitters, genes, circuits. HiTOP, even though it is rigorous math, is still based on symptoms—on what people feel and say and do. To the hard-liners at the NIMH, that is still “psychology,” not “biology.”

A Proposed Layered Architecture

What would a better architecture look like? Maybe something like this:

| Layer | Nature | Examples | Treatment Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Layer 1: Neurodevelopmental | Structural brain differences present early. | Intellectual Disability, Severe Autism | Habilitation, accommodation, support. |

| Layer 2: Genetic/Endogenous | Strong biological basis (“Dopamine Disorders”). | Schizophrenia, Bipolar I | Pharmacology primary; therapy as support. |

| Layer 3: Dysregulation | System imbalance due to trauma/environment. | Depression, Anxiety, PTSD | Therapy often primary; medication as scaffold. |

| Layer 4: Characterological | Rigid patterns of living and learned responses. | Personality Disorders | Long-term insight/relational therapy. |

| Layer 5: Systemic | Problems in environment/relationships. | Poverty, Abuse, Systemic Racism | Social work, policy change, family therapy. |

Part XVII: Rebecca Goldstein and the Mattering Problem

What Mental Health Actually Is

Maybe we need to stop and ask a basic question: what is mental health? The DSM defines disorders but never defines health.

Philosopher Rebecca Goldstein offers a crucial insight here with her concept of the “Mattering Map.” She argues that humans are driven by a need to matter—to feel significant to ourselves and others. We map our lives according to what gives us this sense of significance.

In The Mind-Body Problem, she writes: “The map in fact is a projection of its inhabitants’ perceptions. A person’s location on it is determined by what matters to him, matters overwhelmingly… who are the nobodies and who the somebodies.”

When this map breaks—when a person can no longer find a way to matter, or when the map they have been following leads them into a dead end—we call it “mental illness.” Clinical depression, in Goldstein’s view, is the conviction that “you don’t and will never matter.” It is the collapse of the map.

The Patient-Centered Question

The simplest test of mental health is not “do you meet criteria for a disorder,” but rather: Is what you’re doing working for you? Are your beliefs and behaviors helping you live the life you want?

Part XVIII: The Coming Crisis

The Ticking Clock

The system is unstable. It can’t hold. We have a diagnostic manual that the government’s own research agency says is scientifically invalid. We have a profession split between clinicians using one paradigm and researchers using another. We have insurance companies demanding categorical diagnoses for a reality that’s dimensional. We have an epidemic of mental health problems and a workforce that can’t meet the demand.

Something will break. The question is when and how. Theodore Porter would say that the transition will probably come during a recession, when the economic pressure on healthcare systems becomes unbearable, when someone decides we can’t afford to keep doing things the inefficient old way. That’s often when bureaucratic revolutions happen. Crisis creates the opening for change.

The Synthesis We’re Waiting For

The DSM was never a description of nature. It was a set of administrative protocols created by the military, adapted by bureaucracy, defended by a profession fighting for legitimacy, and captured by industries seeking profit. It achieved reliability by sacrificing validity.

The NIMH’s RDoC is an honest acknowledgment that the labels don’t work for science. But it’s also a retreat into pure materialism: a decision to study the machine while ignoring the ghost. It has no place for meaning, for narrative, for the human experience of suffering.

We’re left with a split. The DSM is a map of human stories that has no biological grounding. RDoC is a biological map that has no human stories. Neither one, alone, can guide treatment.

We need a synthesis. We need a system that admits its assumptions. We need to stop pretending the categories are carved in nature and start asking: “Is this map useful?” Science isn’t a story we tell once and then repeat forever. It’s a process of revising our maps when they stop matching the territory. The DSM has become a story that can’t be revised. The story will change. The only question is whether we’ll change it carefully, or wait until the whole thing collapses.

Bibliography

- American Psychiatric Association. (1952, 1968, 1980, 1994, 2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

- Andreasen, N. C. (2007). DSM and the death of phenomenology in America. Schizophrenia Bulletin.

- Bentall, R. P. (2004). Madness Explained: Psychosis and Human Nature. London: Penguin Books.

- Campbell, J. (1949). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Cosgrove, L., & Krimsky, S. (2012). A comparison of DSM-IV and DSM-5 panel members’ financial associations with industry. PLOS Medicine.

- Cuthbert, B. N., & Insel, T. R. (2013). Toward the future of psychiatric diagnosis: The seven pillars of RDoC. BMC Medicine.

- Davies, J. (2013). Cracked: Why Psychiatry is Doing More Harm than Good. London: Icon Books.

- Foucault, M. (1961). Madness and Civilization. New York: Pantheon.

- Frances, A. (2013). Saving Normal. New York: William Morrow.

- Goldstein, R. N. (1983). The Mind-Body Problem. New York: Random House.

- Goldstein, R. N. (2016). The Mattering Instinct. Edge.org.

- Greenberg, G. (2013). The Book of Woe: The DSM and the Unmaking of Psychiatry. New York: Blue Rider Press.

- Harrington, A. (2019). Mind Fixers. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Hyman, S. E. (2010). The diagnosis of mental disorders: the problem of reification. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology.

- Insel, T. (2013). Director’s Blog: Transforming Diagnosis. National Institute of Mental Health.

- Kotov, R., et al. (2017). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP). Journal of Abnormal Psychology.

- Moncrieff, J., et al. (2022). The serotonin theory of depression: A systematic umbrella review. Molecular Psychiatry.

- Porter, T. M. (1995). Trust in Numbers. Princeton University Press.

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science.

- Szasz, T. S. (1961). The Myth of Mental Illness. New York: Harper & Row.

- Timimi, S. (2017). Non-diagnostic based approaches to helping children who could be labelled ADHD. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being.

- van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. New York: Viking.

- Whitaker, R. (2010). Anatomy of an Epidemic. New York: Crown.

- Whooley, O. (2019). On the Heels of Ignorance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Joel Blackstock, LICSW-S, is the Clinical Director of Taproot Therapy Collective in Hoover, Alabama. He specializes in complex trauma treatment and writes at GetTherapyBirmingham.com.

0 Comments