Before we begin our discussion of synesthesia consider this passage from The Peregrine. One of my favorite books. It is a bird watching journal of a naturalist but it is beautifully in its scope and transcendental description:

Before we begin our discussion of synesthesia consider this passage from The Peregrine. One of my favorite books. It is a bird watching journal of a naturalist but it is beautifully in its scope and transcendental description:

“The first bird I searched for was the nightjar, which used to nest in the valley. Its song is like the sound of a stream of wine spilling from a height into a deep and booming cask. It is an odorous sound, with a bouquet that rises to the quiet sky. In the glare of day it would seem thinner and drier, but dusk mellow it and gives it vintage. If a song could smell, this song would smell of crushed grapes and almonds and dark wood. The sound spills out, and none of it is lost. The whole wood brims with it. Then it stops. Suddenly, unexpectedly. But the ear hears it still, a prolonged and fading echo, draining and winding out among the surrounding trees. Into the deep stillness, between the early stars and the long afterglow, the nightjar leaps up joyfully. It glides and flutters, dances and bounces, lightly, silently away. Sparrowhawks were always near me in the dusk, like something I meant but could never quite remember.”

Let’s look at the things going on in these passages.

In the glare of day it would seem thinner and drier, but dusk mellow it and gives it vintage

He describes the sound as having a smell and the smell changing based on the color and texture of the light and air.

Sound is being compared to the visual of pouring wine into a cask.

stream of wine spilling from a height into a deep and booming cask

The perception of sound in the inner world endures after the sensation of sound in the outer world has ended

the ear hears it still, a prolonged and fading echo, draining and winding out among the surrounding trees

We know that we can’t see sound, we can’t taste it, we can’t see or smell it. Yet this description of birdsong tickles our other senses involving them in the sensation of sound. You might hear style writers describe colors or patterns as “loud” or food writers describe taste as “shining” or “dull”. This is obviously a synesthetic association since the writers are not talking about the food’s ability to reflect light or make noise.

Synesthesia is a fascinating phenomenon where the stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway triggers an involuntary experience in another. This intermingling of the senses can result in extraordinary perceptions, where individuals might associate colors with numbers, taste shapes, or even hear sounds when seeing certain images. This can happen in psychosis, trauma to the brain when we take a psychedelic but it also happens partially to almost everyone under normal circumstances.

Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin, coined the term “synesthesia” and began documenting various cases but it is a very old phenomenon in our psyche. Synesthetic experiences have left traces throughout human history, manifesting in ancient mythology, art, and religious practices.

The concept of “rasa” in Indian aesthetics associates emotions with specific colors, tastes, and musical tones. For example, the emotion of love (shringara) is often associated with the color red, the taste of sweetness, and melodious musical tones. In the works of Greek poet Sappho, there are references to synesthetic experiences, such as the blending of fragrances with sounds and emotions. For example, in one fragment, Sappho writes, “As I listen, the faint scent of lemon trees rises in the sound of your voice.”

The concept of “rasa” in Indian aesthetics associates emotions with specific colors, tastes, and musical tones. For example, the emotion of love (shringara) is often associated with the color red, the taste of sweetness, and melodious musical tones. In the works of Greek poet Sappho, there are references to synesthetic experiences, such as the blending of fragrances with sounds and emotions. For example, in one fragment, Sappho writes, “As I listen, the faint scent of lemon trees rises in the sound of your voice.”

The poems of Persian poet Rumi often employ synesthetic language to describe spiritual experiences. For example, he writes, “The flute of the infinite is played without ceasing, and its sound is love… Whoever hears this sound merges in it.” In Psalm 34:8 in the bible, there is a synesthetic description: “Taste and see that the Lord is good.” Here, the act of tasting is metaphorically linked with experiencing the goodness of God. These ancient poets use synesthesia like associations to enhance the transcendental effect of their writing.

The Hindu philosophy of chakras posits that there are associations and cross activation between somatic experiences in different parts of the body, colors, emotion and sometimes sound frequencies. Chakras could have provided our ancestors with a framework to understand and regulate their physical and emotional well-being. By linking specific emotions and bodily sensations to different energy centers represented by chakras, individuals may have been able to identify and address imbalances in their physical and emotional states.

The color associations with chakras may have served as a visual aid to enhance the focus and awareness of these energy centers during meditation and spiritual practices. Colors can have psychological and physiological effects on individuals, and using specific colors in association with chakras might have facilitated a deeper connection with and activation of these energy centers. Synesthesia may have helped shaman and philosophers perceive these cross sensory associations to teach others these connections.

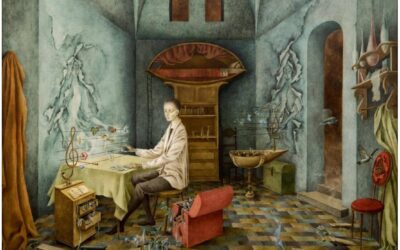

Synesthesia also found expression in the works of artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, one of my favorite artists who sought to capture the fusion of senses on canvas.

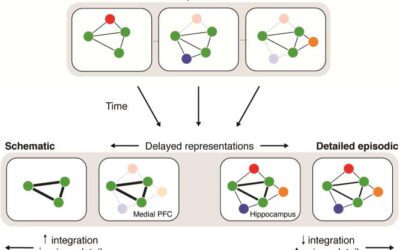

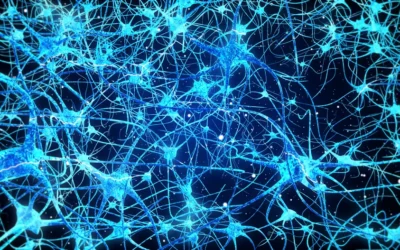

Synesthesia has also been linked to increased neural plasticity, which is the brain’s ability to reorganize and establish new connections. It is thought that in individuals with synesthesia, there may be heightened neural plasticity in certain brain regions or circuits. Highly intuitive people like poets or artists might be more naturally able to form synesthetic connections. Genetic factors may influence brain development and the formation of neural connections during early stages of life, predisposing individuals to synesthetic experiences.

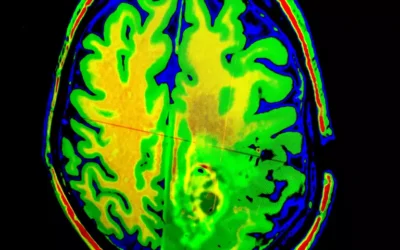

Recent advances in neuroscience have shed light on the underlying mechanisms behind synesthesia. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have revealed distinct patterns of brain activity in synesthetes compared to non-synesthetes. These studies indicate that synesthesia involves hyperconnectivity and increased communication between brain regions associated with different sensory modalities, allowing for the cross-activation of sensory pathways.

While extreme synesthesia can cause deficits and impairment, mild forms are present in artistic people and some variants are common in everyone. Personification, for example, is a literary device where human attributes are ascribed to non-human entities, such as describing the wind as “whispering” or the flowers as “smiling.” Personification is not always a literary device though. We all personify different things. A stone might look like a person or a car grill like a smile.

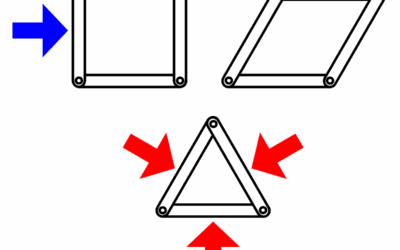

Take a look at the shapes below:

The majority of people will associate the rounded shape with the name Bubu and the pointed shape with the name Kiki. What would you name the shapes if you had to pick between those names?

Even though there is no logical basis for shapes to have names, these names “make sense” to us. The connection between higher pitched and lower pitched vowel sounds our brains associate with a sharp or round shape even though sound and shape have no logical connection. Sound symbolism is a neurotypical association between certain speech sounds and particular perceptual or sensory qualities. It suggests that certain sounds have inherent meanings or convey specific qualities, independent of the linguistic context.

In sound symbolism, there is a tendency for people to perceive a correspondence between the sounds of words and the meaning or qualities associated with those words. The sound properties of a word seem to imitate or reflect the qualities of the object, action, or concept it represents. This phenomenon has been observed across different languages and cultures.

For example, many languages show a tendency to associate certain speech sounds with size or shape. Words that convey smallness or lightness often contain high-pitched vowels or consonants produced towards the front of the mouth, while words denoting largeness or heaviness may have lower-pitched sounds or consonants produced towards the back of the mouth. This pattern can be observed in words like “tiny” versus “big” or “light” versus “heavy.”

Sound symbolism is the synesthetic phenomenon behind the association with the names Kiki and Bubu with angular or rounded shapes. Sound symbolism can also extend to other sensory qualities beyond size or shape. Certain speech sounds may be associated with qualities such as smoothness, roughness, brightness, darkness, or hardness. These sonic associations can influence people’s perceptions and expectations of objects, events, or concepts.

In my articles about architecture I argue that there are evolutionary basis for different forms of art and design. Additionally, recent studies have indicated that associations between taste and shape are different among cultural groups. Westerns had different shape associations with taste than rural African tribes. This means that the associations between taste and sound and other sensory associations are more cultural. Our brain has the ability to rewrite these associations based on our environment and relatively recent events. This makes sense as things like climate, environment, food sources and culture change relatively quickly over tens to hundreds of years.

In my articles about architecture I argue that there are evolutionary basis for different forms of art and design. Additionally, recent studies have indicated that associations between taste and shape are different among cultural groups. Westerns had different shape associations with taste than rural African tribes. This means that the associations between taste and sound and other sensory associations are more cultural. Our brain has the ability to rewrite these associations based on our environment and relatively recent events. This makes sense as things like climate, environment, food sources and culture change relatively quickly over tens to hundreds of years.

Colors and emotions are often linked in various languages, such as the phrase “seeing red” to describe anger. A research study conducted across 30 countries discovered that people from diverse cultures share common associations between colors and emotions, suggesting a universal aspect to these connections. Interestingly, languages that are more similar to each other tend to exhibit similar color-emotion associations. For instance, English, French, and German speakers employ color metaphors to convey emotions like anger, sadness, or envy, albeit with slight variations in the specific colors used.

The networks in the brain need the ability to rewire and form new associations between our senses and emotions. This kept our instincts relevant and kept us alive as we evolved. For example, we might associate colors like red, blue and orange with food if we eat a lot of blueberries, oranges or raspberries. In an environment without those foods our associations would need to change. Other colors or shapes would activate dopamine and taste receptors as our diet changed.

Some of these associations between emotions, color and sensation run deeper into the brain based on how relevant the need for the association is. For example, the “shape” of taste might be a relatively recent association due to culture and might vary based on genetic groups. Associations with fire or sharp angles might have a deeper neural pathway in the brain and more ancient association. Poisonous snakes often have triangular head. Predators have sharp pointed teeth. Prehistoric art usually portrays predators like wolves and bears with a triangular shape, whereas most human depictions are rounded or circular. It is possible that this is the reason that we perceive rounded shapes with safety and angular shapes with danger.

Edward Edinger points out in his book, Ego and Archetype that most children draw the self as a circle in early life. His book follows Rhoda Kellog’s 1970’s studies on children’s art. He believed that the reason that primitive man associated themselves with the circle was because of our dependance on the sun and moon. Primitive humans associated themselves with the main sources of light because light was our most essential need for our survival. The first carvings of humans from the stone age are called Venus figurines. Venus figurines had accentuated round maternal forms of hips and breasts. Even today we make road signs that indicate danger into triangles where more benign road indicators are squared or rounded. .

Edward Edinger points out in his book, Ego and Archetype that most children draw the self as a circle in early life. His book follows Rhoda Kellog’s 1970’s studies on children’s art. He believed that the reason that primitive man associated themselves with the circle was because of our dependance on the sun and moon. Primitive humans associated themselves with the main sources of light because light was our most essential need for our survival. The first carvings of humans from the stone age are called Venus figurines. Venus figurines had accentuated round maternal forms of hips and breasts. Even today we make road signs that indicate danger into triangles where more benign road indicators are squared or rounded. .

Synesthesia helped us listen to the pattern and shapes of nature and is related to evo psyche and carl jung’s theory of archetypes. Pointed head snakes pointy nuts colors indicate taste. This would need to vary plasticity as we migrated and went different places. Studies have shown different cultural and genetic groups have different associations between taste and shape.

There is an enormous difference between information being processed by the brain and information being perceived by our conscious ego. In everyday life, our senses constantly receive an enormous amount of information from the environment. To prevent us from being overwhelmed, our brain filters out certain sensory inputs that it deems less important or redundant. This filtering process is known as sensory gating.

Sensory gating involves two main stages: the first stage is called “sensory registration,” where the brain initially detects and registers the sensory information. The second stage is the “sensory filtering” process, which filters out unnecessary information to avoid overload. For example our eyes perceive two separate images with interference and gaps where blood vessels and shadows distort the visual receptors. Our brain does not show us this. It applies what is essentially an AI filter that edits the two images together and makes “guesses” about what to put in the gaps of the visual field. This filtering helps us focus on relevant stimuli and prevents us from becoming overwhelmed by every little sensory input.

In individuals with schizophrenia, there may be abnormalities in the brain’s sensory gating mechanism. This can result in an impaired ability to filter out irrelevant or contradictory sensory information effectively. Sometimes it results in stimuli being filtered into multiple or the wrong sensory channels. As a result, individuals with schizophrenia may experience difficulties in distinguishing between relevant and unimportant sensory inputs. This can lead to sensory overload, where various sensory stimuli compete for attention, causing confusion and making it challenging to concentrate on relevant information.

Creativity and intuition in humans may be caused by gaps in sensory gates that allow for unorthodox ways of information being processed. This is the reason that creative and intuitive individuals are more aware of unconscious processes and more able to see through arbitrary rules and norms in culture. They may have a small genetic predisposition to have an imperfect sensory gate while morte traditional individuals have information filtered neatly into each sense.

It has long been speculated that schizophrenia might be an over abundance and over expression of the same genes that lead to the creation of new perspectives and new ideas. Creativity and intuition can help us see how to color outside the lines, but when there are too many of these tendencies we cannot see the lines at all. Joseph Campbell used to say that the artist swims in the ocean that the schizophrenic drowns in. He meant that the deep layers of the unconscious can enrich us but that if we go too deep they cause us to lose ourselves. The archetypes are roots of consciousness but we should not dig them all up.

Our senses are not as distinct of entities as we would like to make them. We think about senses in an ordered way. The ear hears sound, and the brain then perceives sound; but this is not how the brain works. All of our senses are blended together and send messages to our body and emotional system before the brainstem filters them for us and lets us know how to perceive them consciously. The ego consciousness in our self perception is one of the SMALLEST parts of our cognition. What we think we are is one of the smallest parts of what we actually are. Our brain does an enormous amount of work before the sensations we perceive are presented to our ego on a silver platter.

The keys to unlocking our psychology lies in understanding synesthesia and this spaghetti bowl mess of perception taking place in our brain at any moment. Treatments like somatic therapy, Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT) and Brainspotting (BSP) use glitches in the way that the brain perceives stimuli, emotion and our sense of self to treat trauma. Older traditions like chakras and transcendental meditation are based on utilizing the same glitches in perception. While brainspotting uses eye position, EMDR uses eye movement and ETT therapy uses color as a trigger to release trauma from the deep brain.

Color has long been recognized as a powerful stimulus that can elicit emotional and psychological responses in humans. It is suggested that color can influence emotional states and evoke specific responses, potentially affecting the processing and regulation of trauma-related emotions. Much of these happens during base unconscious levels of cognition before we can perceive what is happening cognitively. From an evolutionary perspective, the impact of color on trauma and psychology can be explained by the principle of biophilia, which suggests that humans have an innate tendency to connect with nature. We evolved as a part of the natural world and still respond unconsciously to elements from the natural world.

Color has long been recognized as a powerful stimulus that can elicit emotional and psychological responses in humans. It is suggested that color can influence emotional states and evoke specific responses, potentially affecting the processing and regulation of trauma-related emotions. Much of these happens during base unconscious levels of cognition before we can perceive what is happening cognitively. From an evolutionary perspective, the impact of color on trauma and psychology can be explained by the principle of biophilia, which suggests that humans have an innate tendency to connect with nature. We evolved as a part of the natural world and still respond unconsciously to elements from the natural world.

Color plays a crucial role in our relationship to nature, as it is the most perceivable sensation in the natural environment. Throughout evolution, humans have developed an association between specific colors and their surroundings, allowing them to recognize important cues for survival, as we discussed earlier. Eg ripe fruits, poisonous plants, fire and animals.

Evolutionary psychology and archetypal theories propose that certain colors have deep-rooted symbolic meanings and can evoke archetypal responses within us. These archetypes are thought to be universal and inherited, representing fundamental human experiences and emotions. For example, red can evoke a sense of passion, energy, or danger, while blue may elicit feelings of calmness, tranquility, or sadness. These archetypal associations with colors may have developed over time as adaptive responses to the environment.

Regarding the ETT (Emotional Transformation Therapy) and its use of specific colors, hypothetical mechanisms can be derived from both evolutionary and Jungian standpoints. ETT utilizes a set of color filters that influence emotional states and facilitate therapeutic transformation. From an evolutionary perspective, the colors and light directions used in ETT might tap into our primal associations with certain environments or situations. For instance, using calming shades of green or blue might activate our innate connection to natural landscapes, triggering relaxation responses and potentially reducing stress or trauma-related symptoms.

Regarding the ETT (Emotional Transformation Therapy) and its use of specific colors, hypothetical mechanisms can be derived from both evolutionary and Jungian standpoints. ETT utilizes a set of color filters that influence emotional states and facilitate therapeutic transformation. From an evolutionary perspective, the colors and light directions used in ETT might tap into our primal associations with certain environments or situations. For instance, using calming shades of green or blue might activate our innate connection to natural landscapes, triggering relaxation responses and potentially reducing stress or trauma-related symptoms.

From a Jungian standpoint, the colors employed in ETT might be chosen based on their archetypal symbolism. For example, warm colors like red or orange could be utilized to activate the archetype of vitality and energy, promoting a sense of empowerment and motivation in the therapeutic process. Similarly, cool colors like blue or purple might evoke archetypes of healing, tranquility, and introspection, supporting emotional processing and self-reflection.

Our brain filters this energy into five or some would say 6 senses but it is really electrical impulses and energy that could be filtered together and influence each other

Synesthesia continues to intrigue scientists, artists, and individuals alike, providing a unique window into the intricate workings of the human brain. Synesthesia is not the way we think. It is a byproduct of the way we think. Through understanding it we can better understand ourselves and how to heal. All of our senses come from a giant stew pot that the brain must filter into specific ingredients. They have marinated and influenced the taste of one another before they are picked out of the stew as individual items. A more holistic understanding of psychology can lead us to a more holistic understanding of who and what we are. Accepting all the depth and complexity beneath cognition can help us get a better sense for what makes us human.

Here’s a little joke before we go.

A guy points at a man on the train and says under his breath to his friend “Hey I heard that guy has synesthesia”.

The guy with synesthesia goes “Hey! I smelled that!”.

Did you enjoy this article? Checkout the podcast here: https://gettherapybirmingham.podbean.com/

References:

- Cytowic, R. E., & Eagleman, D. M. (2011). Wednesday is indigo blue: Discovering the brain of synesthesia. MIT Press.

- Ramachandran, V. S., & Hubbard, E. M. (2001). Synaesthesia–a window into perception, thought and language. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8(12), 3-34.

- Ward, J. (2013). Synesthesia. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 49-75.

- Simner, J., & Hubbard, E. M. (Eds.). (2013). The Oxford handbook of synesthesia. Oxford University Press.

- Smilek, D., Dixon, M. J., Cudahy, C., & Merikle, P. M. (2002). Synesthetic color experiences influence memory. Psychological Science, 13(6), 548-552.

- Rouw, R., & Scholte, H. S. (2007). Increased structural connectivity in grapheme-color synesthesia. Nature Neuroscience, 10(6), 792-797.

- Edinger, E. F. (1972). Ego and archetype: Individuation and the religious function of the psyche. Shambhala Publications.

- Jung, C. G. (1968). The archetypes and the collective unconscious. Princeton University Press.

- Kellog, R. (1970). Analyzing children’s art. National Press Books.

- Baker, J. R. (1967). The peregrine. HarperCollins.

Further Reading:

- Duffy, P. L. (2001). Blue cats and chartreuse kittens: How synesthetes color their worlds. Henry Holt and Company.

- Van Campen, C. (2007). The hidden sense: Synesthesia in art and science. MIT Press.

- Marks, L. E. (1978). The unity of the senses: Interrelations among the modalities. Academic Press.

- Sagiv, N., & Ward, J. (2006). Crossmodal interactions: Lessons from synesthesia. Progress in Brain Research, 155, 259-271.

- Spector, F., & Maurer, D. (2009). Synesthesia: A new approach to understanding the development of perception. Developmental Psychology, 45(1), 175-189.

- Grossenbacher, P. G., & Lovelace, C. T. (2001). Mechanisms of synesthesia: Cognitive and physiological constraints. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5(1), 36-41.

- Hubbard, E. M., & Ramachandran, V. S. (2005). Neurocognitive mechanisms of synesthesia. Neuron, 48(3), 509-520.

- Maurer, D., & Mondloch, C. J. (2005). Neonatal synesthesia: A re-evaluation. In L. C. Robertson & N. Sagiv (Eds.), Synesthesia: Perspectives from cognitive neuroscience (pp. 193-213). Oxford University Press.

- Sacks, O. (1995). An anthropologist on Mars: Seven paradoxical tales. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Ramachandran, V. S. (2011). The tell-tale brain: A neuroscientist’s quest for what makes us human. W. W. Norton & Company.Read More Depth Psychology Articles:Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

Jungian Topics

How Psychotherapy Lost its Way

Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality?

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing FictionHow the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jungian Thought to Combat Addiction

Jungian Exercises from Greek Myth

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Post Post-Moderninsm and Post Secular Sacred

Jungian Analysts

Anthropology

Mystics and Gurus

Philosophy

Spirituality

0 Comments