A strategic analysis of what 2024-2025 research reveals about molecular mechanisms, precision psychobiotics, fecal transplants, the forgotten fungal kingdom, and why 30-40% of treatment-resistant patients may finally have answers.

For a century, psychiatry searched for the source of mental illness inside the skull. Depression was a brain disorder. Anxiety was a brain disorder. The treatments—SSRIs, SNRIs, benzodiazepines—were all designed to manipulate brain chemistry directly. When they failed (and they fail 30-40% of the time), the assumption was that we hadn’t yet found the right brain target.

The research of 2024-2025 suggests we may have been looking in the wrong organ entirely.

The Microbiota-Gut-Brain (MGB) axis has matured from theoretical curiosity to mapped territory with defined molecular targets, proven interventions, and a pharmaceutical pipeline rivaling traditional CNS drug development. We now know that specific gut bacteria produce specific metabolites that regulate specific ion channels in the amygdala’s fear circuitry. We can predict which depressed patients will respond to fecal transplants based on whether they have comorbid IBS. We can diagnose depression through fungal biomarkers in stool samples with near-perfect accuracy in research settings.

This isn’t wellness advice about eating yogurt. This is precision medicine targeting a newly understood organ system—and it’s reshaping how we think about trauma, treatment resistance, and the biological foundations of psychological suffering.

The Indole Breakthrough: A Molecular Explanation for Anxiety

The most significant discovery of early 2025 may be the identification of a direct metabolic pathway linking gut bacteria to the brain’s fear circuitry. Stanford Medicine’s synthesis of the field confirms that the gut-brain connection has moved from hypothesis to established science—but the breakthrough came from understanding exactly how that connection operates at the molecular level.

For years, tryptophan metabolism was implicated in mental health because tryptophan is the precursor to serotonin. But research published in February 2025 shifted focus to a different class of tryptophan metabolites: indoles. Certain gut bacteria expressing the tnaA gene convert dietary tryptophan into indoles. These small molecules enter the bloodstream, cross the blood-brain barrier, and target the basolateral amygdala (BLA)—the brain region responsible for processing emotional salience, fear, and anxiety.

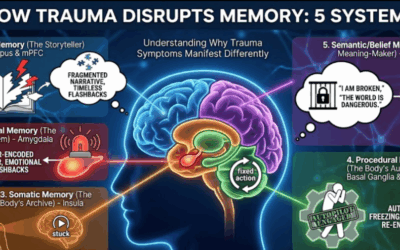

The mechanism is elegant. Indoles interact with calcium-dependent SK2 channels on BLA neurons. These channels function as a “brake” or “clutch” on neuronal firing. When sufficient indoles are present, SK2 channels activate, preventing neurons from becoming hyperexcitable. In germ-free animal models or dysbiotic states where indole-producing bacteria are depleted, this molecular brake fails. BLA neurons enter a state of hyperexcitability, manifesting as heightened anxiety and exaggerated fear responses.

Earlier research on indole signaling had established that these metabolites mediate host-microorganism chemical communication during dysbiosis. The 2025 work demonstrates precisely how that communication regulates emotional states. For clinicians, this opens concrete possibilities: “postbiotic” therapies delivering indoles directly, or probiotic strategies using high-indole-producing strains to restore the amygdala’s natural brake system.

This connects directly to what we understand about finding the roots of trauma in the deep brain. The amygdala has always been central to our understanding of fear and threat processing—now we know its excitability is partly regulated by what’s happening two feet south of the skull.

The Neural Highway: Vagus Nerve as Interoceptive Organ

The vagus nerve (Cranial Nerve X) remains the primary physical conduit of the gut-brain axis. But our understanding has deepened considerably. The vagus is no longer seen merely as a parasympathetic regulator of digestion—it is the primary organ of interoception, the brain’s sensing of the body’s internal state.

As the Journal of Neuropsychiatry has detailed, approximately 80-90% of vagal fibers are afferent, carrying information from gut to brain rather than the reverse. Specialized enteroendocrine cells in the gut lining detect microbial metabolites—short-chain fatty acids, neurotransmitters, inflammatory signals—and synapse directly with vagal afferent fibers. This forms what researchers call a “synaptic-like” connection transmitting information to the brainstem’s Nucleus Tractus Solitarii within milliseconds.

Dysbiosis alters this signaling code. Pathogenic bacteria or a lack of beneficial metabolites can trigger vagal signals that the brain interprets as “sickness,” driving the lethargy, anhedonia, and social withdrawal characteristic of depression. The brain isn’t fabricating symptoms—it’s receiving genuine signals of distress from below.

Crucially, the vagus nerve mediates the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Stimulation of the vagus nerve inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines from macrophages, protecting the brain from neuroinflammation. When vagal tone is low—as it often is in chronic stress and depression—this protective reflex weakens. Gut inflammation rises unchecked, inflammatory signals cross into the brain, and microglia activate to “prune” synaptic connections.

Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS)—a non-invasive technique using an ear-clip device—has shown promise not just for depression, but for metabolic-depression comorbidities. In animal models of diabetes-induced depression, taVNS simultaneously improved glucose metabolism, reduced systemic inflammation, and alleviated depressive behaviors.

Even more intriguingly, research shows that taVNS can prevent stress-induced dysbiosis—effectively treating the gut from the brain. The vagal pathway runs both directions, and stimulating it from above can protect the gut ecosystem below. This complements the neuromodulation approaches already available for treatment-resistant conditions.

The Immunological Highway: Leaky Gut and Systemic Inflammation

The “inflammatory theory of depression” has received substantial validation through gut-brain research. The integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier is paramount. In states of chronic stress or dysbiosis, the tight junction proteins that seal the gut lining are downregulated.

This “leaky gut” allows the translocation of bacterial endotoxins—specifically lipopolysaccharides (LPS)—into the bloodstream. The immune system recognizes LPS as a threat, mounting a systemic response characterized by elevated levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6. These cytokines cross the blood-brain barrier or stimulate vagal afferents to trigger microglial activation, leading to neuroinflammation.

Recent studies confirm that psychobiotics and FMT exert their antidepressant effects partially by reinforcing tight junctions—”closing the gate” on inflammation. The increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 following probiotic administration further dampens this systemic fire, creating a neurochemical environment conducive to recovery.

This is why the question “How is your digestion?” is now clinically relevant in psychiatric assessment. Chronic gut symptoms alongside mood symptoms may indicate a patient whose depression is fundamentally inflammatory—driven by a leaky gut that no amount of cognitive restructuring will address. Understanding the body-brain connection means recognizing that sometimes the body is the problem.

Psychobiotics Enter the Precision Era

The term “psychobiotic” was coined to describe live bacteria conferring mental health benefits. But 2024-2025 literature signals a critical shift: from broad-spectrum “probiotics” to Precision Psychobiotics—strains selected for specific mechanisms of action targeting defined neurochemical pathways.

A systematic review of 19 RCTs published in 2025 crystallized the evidence with nuanced, clinically important findings.

Psychobiotics work best as adjuncts, not replacements. In trials where probiotics were added to standard antidepressant regimens, 7 out of 10 studies showed significant improvements compared to placebo. As monotherapy for Major Depressive Disorder, results are more mixed—only a subset showed efficacy sufficient to induce remission. For severe depression, psychobiotics function best as “biological primers” optimizing the physiological environment for other treatments to work.

Anxiety responds more consistently than depression. Psychobiotics appear particularly effective for the anxiety component of mood disorders. In surgical oncology patients, psychobiotic treatment prevented the 39.7% increase in anxiety seen in the placebo group—effectively stabilizing mood against severe physiological stress.

Specific strains do specific things. The days of generic probiotic blends are ending.

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum PS128 increases dopamine and serotonin in the striatum and prefrontal cortex. A pivotal study in adolescents showed it significantly reduced depression scores (HAM-D dropped 4.2 points) and improved emotion recognition. However, results in adults have been more variable—a 2024 study in adult MDD patients found no significant change in core depressive symptoms, though gut permeability markers improved. This discrepancy suggests an age-dependent window of efficacy, potentially linked to adolescent brain plasticity.

Bifidobacterium breve shows sex-specific effects, enhancing reward responsiveness (a counter to anhedonia) specifically in female subjects (SMD = 0.61). This suggests the microbiome-brain interaction is modulated by sex hormones, pointing toward a future where psychobiotic prescriptions account for biological sex.

Lactobacillus gasseri CP2305 utilizes the vagus nerve to exert its effects, improving sleep quality and reducing salivary cortisol in adults under chronic stress. By acting on the HPA axis, it serves as a “stress buffer” preventing the cortisol cascade that often precipitates depressive episodes.

The L. helveticus R0052 + B. longum R0175 combination (often branded as Probio’Stick) remains the gold standard. New data from the ProDeCa study continues to validate its use, showing significant improvements in cognitive function (SMD = 0.48) and reductions in depression, cortisol, and self-blame scores.

Why does a strain work for Patient A but not Patient B? The emerging answer involves “colonization resistance”—if a patient’s resident microbiome is robust, it may prevent the introduced psychobiotic from establishing itself. The probiotic passes through without effect. Without appropriate prebiotic fiber to fuel them, even well-chosen psychobiotics may be metabolically inert. This is why the synergy of diet and supplementation matters so much.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: The “Reset” Button

If psychobiotics are a gentle nudge to the gut ecosystem, Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) is a terraforming event. By transferring the entire microbial community from a healthy donor, FMT aims to completely overwrite the dysbiotic state. In 2024-2025, FMT has matured from experimental procedure to evidence-based intervention for neuropsychiatry.

A comprehensive meta-analysis covering trials through late 2024 provides the most definitive efficacy data to date. Across 12 RCTs involving 681 participants, FMT demonstrated a significant reduction in depressive symptoms with a large effect size (SMD = -1.21).

But the devil is in the details. Subgroup analysis reveals that FMT is most effective in patients with comorbid Irritable Bowel Syndrome and depression (SMD = -1.06) compared to those with “pure” psychiatric diagnoses (SMD = -0.67). This strongly supports the existence of a “Gut-Origin Depression” phenotype. For patients whose depression is biologically linked to gut dysbiosis—manifesting as IBS symptoms—fixing the gut fixes the mood. For patients whose depression is driven by other factors (trauma, genetics, life circumstances), FMT is less impactful.

This has profound clinical implications. Not every depressed patient needs FMT. But for the subset with clear gut-mood connections—chronic digestive symptoms alongside mood symptoms—FMT may offer something SSRIs never could: addressing the actual biological driver rather than downstream neurotransmitter effects.

Delivery methods have evolved. While direct gastrointestinal delivery (colonoscopy/enema) remains statistically superior (SMD = -1.29 vs. -1.06 for capsules), oral fecal capsules are closing the gap and dramatically improving patient acceptance. The non-invasive nature of capsules allows for “maintenance therapy”—repeated doses over time that may be necessary to maintain remission.

Safety data from Parkinson’s trials is reassuring. The pooled rate of adverse events is low, mostly mild gastrointestinal discomfort. Serious adverse events were notably absent in reviewed trials. However, the regulatory landscape is tightening—the FDA has moved to close loopholes allowing unapproved stool banks, requiring microbiome therapeutics to meet strict Investigational New Drug standards.

The Forgotten Kingdom: Gut Fungi and Depression

While 99% of gut-brain research focuses on bacteria, the mycobiome—the fungal community—has emerged in 2024-2025 as a critical, overlooked player. Fungi comprise a small percentage of gut biomass but possess disproportionately large surface area and potent immunomodulatory capabilities.

Recent studies have mapped a distinct “MDD Mycobiome” characterized by expansion of pathogens—elevated Candida (specifically C. albicans) and Aspergillus—alongside depletion of beneficial yeasts like Saccharomyces. These pathogenic fungi degrade the mucin layer of the gut and trigger strong inflammatory responses via Dectin-1 receptors on immune cells, contributing to systemic inflammation increasingly implicated in depression.

A pivotal 2025 study demonstrated remarkable diagnostic power. By analyzing intestinal fungal communities, researchers identified a panel of 22 fungal biomarkers. Using machine learning, this panel distinguished depressed patients from healthy controls with an Area Under the Curve of 1.000 in the study cohort—near-perfect accuracy.

The implication is profound: objective biological testing for depression may be approaching. A stool test measuring these fungal biomarkers could help subtype patients who might benefit specifically from antifungal dietary interventions or treatments. This moves depression from a purely symptom-based diagnosis toward something more biologically grounded—and potentially more precisely treatable.

This finding connects to understanding how inflammation drives psychiatric symptoms. Fungal-triggered inflammatory cascades eventually reach the brain, activating microglia that reduce neurotransmitter availability and synaptic connectivity. Addressing gut fungi might interrupt this cascade at its source—a fundamentally different approach than modulating neurotransmitters downstream.

The Commercial Pipeline: From Supplement to Pharmaceutical

The translation of gut-brain science into commercial reality is accelerating, with the market dividing into consumer health (supplements) and biotech/pharma (FDA-approved drugs). Several companies are advancing sophisticated pipelines that treat the gut-brain axis as seriously as any traditional CNS drug target.

Kallyope, with over $236 million in Series D funding, represents a fundamentally different approach. Rather than selling live bacteria, they focus on gut-restricted small molecules—traditional chemical drugs that don’t enter the bloodstream but act on receptors in the gut lining to trigger signals to the brain. This minimizes systemic side effects while accessing the gut-brain axis. Their pipeline includes programs for metabolism, migraine, and CNS disorders.

Holobiome is mapping specific bacteria to neurotransmitter production, identifying “guilds” of bacteria that cooperate to produce GABA and serotonin. They’re advancing pipelines for depression and pain/gut axis disorders based on this functional mapping—essentially identifying which bacterial consortia work together to produce therapeutic effects.

Bloom Science reported positive Phase 1 data in 2025 for BL-001, a Live Biotherapeutic Product designed to mimic the ketogenic diet’s microbiome effects. The research reveals that the ketogenic diet works partly by fundamentally altering the microbiome—increasing Akkermansia and Parabacteroides—and these shifts mediate its seizure-protective and mood-stabilizing effects. BL-001 aims to deliver these benefits without dietary restriction.

Axial Therapeutics targets the gut-brain axis in autism and Parkinson’s, focusing on sequestering harmful microbial metabolites that cause leaky gut and cross the blood-brain barrier to cause neuroinflammation. Their approach is “subtractive”—removing bad signals rather than adding good bacteria.

32 Biosciences, formed from the merger of two University of Chicago startups, focuses on “Defined Consortia”—synthetic mixtures of strains offering the power of FMT with the precision of a drug. This represents the direction the field is moving: away from donor-dependent transplants toward standardized, reproducible bacterial therapeutics.

The FDA is actively shaping this landscape. Live Biotherapeutic Products are not supplements; they’re drugs requiring Phase 1-3 trials. This raises the barrier to entry, favoring well-funded biotechs over supplement companies—but also ensuring products reaching market have genuine evidence behind them.

The Psychobiotic Diet: Food as Medicine

Beyond pills and transplants, diet remains the most accessible lever for modulating the gut-brain axis. The concept of the “Psychobiotic Diet”—a diet specifically designed to feed mental-health-promoting bacteria—has gained robust clinical support.

The “Gut Feelings” randomized controlled trial demonstrated that a high-prebiotic diet could reduce mood disturbance. The diet emphasizes fiber-rich plants (leeks, onions, artichokes, grains) and fermented foods (kimchi, kefir, sauerkraut). These substrates are fermented by gut bacteria into Short-Chain Fatty Acids like butyrate and acetate. Butyrate is a histone deacetylase inhibitor—an epigenetic regulator—that crosses the blood-brain barrier to upregulate BDNF and reduce neuroinflammation.

This validates what we’ve explored in discussions of synergistic nutrition and mental health: food is not separate from treatment. For clients resistant to supplements or unable to access specialized interventions, dietary modification offers an evidence-based path to supporting the gut-brain axis.

The Challenge of Heterogeneity: Why One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Despite remarkable progress, the field grapples with heterogeneity. Why does a strain work for Patient A but not Patient B? Several factors emerge from the research.

Basal microbiome resistance. If a patient’s resident microbiome is robust and resilient, it may prevent colonization of introduced psychobiotics. The probiotic passes through transiently without establishing itself or exerting effects.

Dietary substrates. Probiotics are living organisms requiring food (prebiotics). Without appropriate dietary fiber to fuel them, expensive psychobiotic supplements may be metabolically inert—present but not functioning.

Genetic factors. Host genetics influence microbiome composition. A strain effective in a European cohort may not translate to an Asian or African cohort due to differing genetic and microbial baselines. Future trials must account for ancestry informative markers.

Sex hormones. The observation that B. breve enhances reward responsiveness specifically in females suggests estrogen and progesterone modulate microbiome-brain interactions. One-size-fits-all approaches may systematically miss sex-specific effects.

The solution lies in responder analysis—identifying biomarkers that predict who will respond to which treatment. We’re moving toward a future where psychiatric evaluation includes gut microbiome panels checking for indole production capacity, fungal dysbiosis markers, and barrier integrity. Not replacing psychological assessment, but adding biological context that shapes treatment selection.

What This Means for Clinical Practice

For psychotherapists, this research doesn’t suggest abandoning psychological intervention for gut-focused treatment. It suggests a more complete picture of what we’re treating.

When a client presents with treatment-resistant depression, the question “How is your digestion?” is now clinically relevant. Clients with significant digestive symptoms alongside mood symptoms—the IBS-depression comorbidity—represent a distinct phenotype that may respond dramatically to gut-focused interventions. The therapeutic strategies we use for experiential and somatic approaches can integrate this understanding: the body is not separate from the psyche.

For clients stuck in therapeutic impasse, the gut-brain axis offers a different angle. Not instead of psychological work, but as biological foundation that might need addressing before psychological work can take hold. A client whose amygdala is in a state of hyperexcitability due to insufficient indole production may experience anxiety that no amount of cognitive restructuring will resolve—because the problem is metabolic, not cognitive.

The path forward for trauma treatment increasingly involves recognizing that the body keeps the score in more ways than we initially understood. Some of what it’s scoring is happening in the gut.

The Bottom Line

The research of 2024-2025 confirms that the future of mental health is systemic. The gut-brain axis is no longer a hypothesis; it is mapped territory with defined molecular targets (indoles, SK2 channels), proven interventions (FMT, precision psychobiotics, taVNS), and a maturing pharmaceutical pipeline.

For clinicians, the implication is clear: evaluating the gut is now part of evaluating the mind. Not for every patient, but for the subset whose depression or anxiety may have biological roots in microbial dysbiosis, fungal overgrowth, or metabolic deficiency.

For patients—especially the 30-40% who haven’t responded to brain-targeted drugs—this research offers something important: a biological explanation for their treatment resistance, and a different target to pursue. The answer to their depression may not be in their head. It may be in their gut.

And for the field as a whole, this represents the dissolution of the cerebrocentric model—replaced by a systemic paradigm where the gastrointestinal tract acts as a primary regulator of emotional valence, cognitive function, and stress resilience. We’re no longer asking whether the gut affects the brain. We’re asking for whom, through what mechanisms, and with what interventions.

Those are the questions of precision medicine. And they’re finally being answered.

References and Further Reading

Mechanistic Research:

Stanford Medicine: The Gut-Brain Connection

PMC: Microbial Metabolites Tune Amygdala Neuronal Hyperexcitability

PubMed: Indole Produced During Dysbiosis Mediates Host-Microorganism Communication

Journal of Neuropsychiatry: The Vagus Nerve and Brain-Gut Axis

Psychobiotics and Clinical Trials:

MDPI: Precision Psychobiotics in Depression – 19 RCT Review

PMC: Precision Psychobiotics for Gut-Brain Axis Health

PubMed: L. plantarum PS128 in Adolescent Depression

PMC: ProDeCa Study – Probiotics’ Effects on Anxiety and Depression

MDPI: Psychobiotics in Surgical Oncology Patients

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation:

PMC: Clinical Efficacy of FMT in Alleviating Depressive Symptoms

PMC: Safety and Efficacy of FMT in Parkinson’s Disease

Mycobiome:

PMC: Gut Mycobiome and Neuropsychiatric Disorders

Frontiers: Metagenomics Reveals Unique Gut Mycobiome Biomarkers in MDD

Vagus Nerve and Bioelectronic Medicine:

PMC: taVNS Regulates Gut Microbiota in Depression

PMC: taVNS Protects Against Stress-Induced Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction

Commercial Landscape:

0 Comments