When Daniel Siegel began examining the neurobiology of attachment relationships in the 1990s, he noticed something that seemed obvious in retrospect but had rarely been articulated explicitly: the mind develops at the interface between relationships and the brain. Neither nature alone nor nurture alone creates who we become. Instead, interpersonal experience literally shapes neural structure, and neural structure constrains what kinds of interpersonal experience we can have. This seemingly simple observation, pursued across three decades of research and clinical practice, gave birth to interpersonal neurobiology, an integrative framework that synthesizes insights from over a dozen scientific disciplines to understand how minds develop, how they can be damaged, and how they can heal.

Siegel’s central contribution involves recognizing integration as the fundamental mechanism underlying mental health. When neural systems are both differentiated and linked, when they maintain their unique identities while also communicating flexibly with each other, the result is a mind characterized by harmony, flexibility, adaptability, coherence, energy, and stability. When integration is compromised, when systems become either rigidly isolated or chaotically blended, mental life moves toward the twin poles of rigidity and chaos that characterize virtually all forms of psychological suffering. This insight applies not only to individual minds but to relationships, families, communities, and societies. Integration, understood as the linkage of differentiated elements, becomes a master principle that organizes understanding across scales from synapses to civilizations.

Daniel Joseph Siegel was born July 17, 1957, and pursued his undergraduate education at the University of Southern California before attending Harvard Medical School, where he received his medical degree in 1983. His postgraduate medical training at the University of California, Los Angeles included pediatrics, child and adolescent psychiatry, and adult psychiatry, giving him an unusually broad clinical foundation. He also served as a postdoctoral fellow in the Bjork Learning and Forgetting Lab at UCLA and as a National Institute of Mental Health Research Fellow, studying family interactions with emphasis on how attachment experiences influence emotions, behavior, autobiographical memory, and narrative.

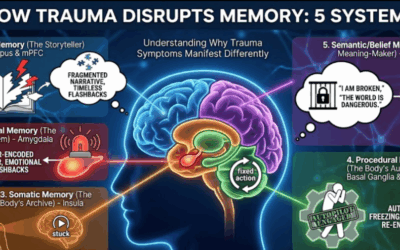

This research background positioned Siegel to recognize patterns that specialized researchers working within single disciplines might miss. When studying attachment, he noticed that secure attachment relationships showed specific neural signatures, particularly in the development of the orbitofrontal cortex, a region of the prefrontal cortex that integrates signals from widely distributed brain areas and regulates everything from bodily states to social perception. When examining memory systems, he observed that traumatic experiences often involve dissociation between implicit memory, bodily sensations, emotions, and behaviors, and explicit memory, the conscious recollection of what happened. When working with clients, he found that healing consistently involved integrating previously disconnected aspects of experience.

These observations coalesced into interpersonal neurobiology, formally introduced in his 1999 landmark book The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. The book synthesized research from attachment theory, cognitive neuroscience, developmental psychology, memory research, emotion regulation, complexity theory, and systems science into a coherent framework. Its central thesis held that the mind emerges from patterns of energy and information flow, both within the body and between people. This definition positions the mind as neither solely neural activity nor purely interpersonal process but rather the emergent property of both, a self-organizing system that regulates energy and information flow across neural, bodily, and relational domains.

The book’s impact on clinical practice proved substantial. Therapists gained a neurobiologically informed understanding of how secure attachment promotes mental health through integration, how trauma fragments mental processes through dissociation, and how therapeutic relationships facilitate healing by providing integrative experiences. The concept that mental disorders reflect either excessive rigidity or excessive chaos, both stemming from impaired integration, gave clinicians a unifying framework for understanding conditions as diverse as depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, dissociative disorders, and borderline personality organization.

The third edition, published in 2020, incorporated over 1,000 additional citations reflecting massive growth in relevant neuroscience research. Yet the core framework remained stable, suggesting that Siegel identified something fundamental about how minds work rather than proposing a theory destined for revision as new findings emerge. The stability of the integration framework across two decades of rapid neuroscience progress represents remarkable predictive validity.

Siegel coined the term mindsight to describe a learnable capacity that underlies emotional and social intelligence. Mindsight involves the ability to perceive one’s own mind, to sense the internal workings of mental processes including thoughts, feelings, sensations, and intentions. It also encompasses the capacity to perceive others’ minds, to construct accurate working models of what another person might be experiencing internally. And crucially, it includes the ability to modify the flow of energy and information in the brain, to actually change neural firing patterns through focused attention.

The concept addresses a paradox in psychological healing. How can someone change patterns they cannot observe? If mental processes operate below awareness, if emotions arise automatically, if attachment patterns formed in preverbal childhood shape adult relationships without conscious knowledge, then insight alone seems insufficient for transformation. Mindsight provides the answer. By developing the capacity to observe mental processes as they occur, to create what Siegel calls a platform of awareness, individuals gain access to processes previously invisible. This observing awareness itself changes the brain, strengthening integrative circuits in the prefrontal cortex that link subcortical processes to conscious reflection.

The distinction between “I am sad” and “I feel sad” illustrates mindsight’s power. The first statement identifies the self with the emotion, collapsing awareness into a single state. The second statement differentiates awareness from the emotion, creating psychological space that allows the person to observe sadness without becoming consumed by it. This differentiation represents the first step toward integration. The observer and the observed must be distinguished before they can be linked in ways that transform the emotional experience from overwhelming to manageable.

Siegel developed the Wheel of Awareness, a meditation practice that systematically cultivates integration across multiple domains. The practice uses the metaphor of a wheel with a central hub representing awareness itself and a rim divided into four segments representing different aspects of experience. The first rim segment encompasses the five external senses: sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. The second segment includes the sixth sense of interoception, bodily sensations arising from muscles, bones, and organs. The third segment contains mental activities including thoughts, emotions, images, and memories. The fourth segment involves relational awareness, the sense of connection to other people and to the larger world.

Practitioners direct focused attention systematically around the rim, spending time with each segment while maintaining connection to the hub of awareness. They notice hearing, seeing, smelling, tasting, touching, then move to bodily sensations, scanning from head to toe. They observe thoughts and emotions as events in consciousness rather than as the totality of consciousness. They attend to the sense of connection and separation in relationships. Finally, in an advanced practice, they bend the spoke of attention back toward the hub itself, cultivating awareness of awareness, the capacity to observe the observing process.

Research on the Wheel of Awareness practice, conducted with thousands of participants, demonstrates significant benefits. Regular practice reduces stress hormone cortisol, enhances immune function, improves cardiovascular health, and shows patterns of brain activity similar to those observed in experienced meditation practitioners. The practice integrates three pillars of mental training: focused attention, which strengthens the capacity to direct and sustain concentration; open awareness, which develops receptivity to whatever arises without grasping or aversion; and kind intention toward self and others, which cultivates compassion and connection.

The neuroplasticity principle underlying the Wheel and mindsight more broadly can be summarized in Siegel’s phrase, where attention goes, neural firing flows, and neural connection grows. This captures the mechanism by which psychotherapy, meditation, parenting, and all forms of learning shape the brain. Attention directed repeatedly toward specific experiences activates particular neural circuits. Activated circuits undergo chemical and then structural changes that strengthen synaptic connections. Strengthened connections create more integrated networks that process information more efficiently and flexibly.

This understanding transforms how we think about therapeutic change. Traditional models often assumed that insight precedes behavioral change, that understanding why you have a pattern allows you to modify it. Interpersonal neurobiology suggests a different sequence. Focused attention on internal experience, even without full understanding, begins changing the brain immediately. New neural connections form. Integration increases. The mind becomes more flexible and adaptive. Understanding may emerge from this integration rather than causing it, or may develop in parallel as integrative practices simultaneously strengthen cortical and subcortical pathways.

Siegel has authored fifteen books, five of them New York Times bestsellers, with translations into over forty languages. Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation (2010) introduced the general public to these ideas, making complex neuroscience accessible through case examples and practical exercises. The Mindful Brain: Reflection and Attunement in the Cultivation of Well-Being (2007) explored how mindfulness practices harness social circuitry to promote mental, physical, and relational health. The Mindful Therapist: A Clinician’s Guide to Mindsight and Neural Integration (2010) applied these principles specifically to therapeutic practice, arguing that therapists’ own mindsight development enhances their effectiveness with clients.

His parenting books have reached millions of readers. Parenting from the Inside Out: How a Deeper Self-Understanding Can Help You Raise Children Who Thrive (2003), co-authored with Mary Hartzell, explores how parents’ own attachment histories and unresolved traumas influence their relationships with their children, and how developing mindsight allows parents to break intergenerational cycles of dysfunction. The Whole-Brain Child: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture Your Child’s Developing Mind (2011) and No-Drama Discipline: The Whole-Brain Way to Calm the Chaos and Nurture Your Child’s Developing Mind (2014), both co-authored with Tina Payne Bryson, provide parents with practical strategies grounded in interpersonal neurobiology for supporting healthy development.

Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain (2013) reframes adolescence not as a period to endure but as a crucial developmental window with unique strengths. Siegel identifies four features of the adolescent mind: novelty seeking, social engagement, increased emotional intensity, and creative exploration. Rather than problems to fix, these represent evolutionarily adaptive characteristics that prepare young people for adult independence. The challenge involves supporting healthy expression of these drives while helping adolescents develop the prefrontal integration needed to make wise choices.

Mind: A Journey to the Heart of Being Human (2017) tackles the deepest question in interpersonal neurobiology: what is the mind? Siegel argues that the mind is not synonymous with brain activity but rather emerges from energy and information flow within the body and between people. This definition positions the mind as fundamentally relational, a hypothesis with profound implications for understanding consciousness, healing, and what it means to be human.

Aware: The Science and Practice of Presence (2018) provides comprehensive instruction on the Wheel of Awareness practice, combining scientific explanation with guided exercises. The book explores presence as a trainable capacity that enhances wellbeing, creativity, and connection. Siegel presents research showing how regular practice literally changes brain structure, increasing integration among cortical regions and between cortical and subcortical systems.

Perhaps Siegel’s most influential contribution beyond his individual writings involves founding the Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology, which has published over one hundred professional books applying the interpersonal neurobiology framework to diverse fields. The series includes works on attachment, trauma, mindfulness, addiction, neurodevelopmental disorders, couples therapy, organizational leadership, education, and contemplative practices. By creating this platform, Siegel enabled dozens of scholars and clinicians to contribute to the developing field, transforming interpersonal neurobiology from one person’s theory into a collaborative interdisciplinary endeavor.

The series includes contributions from luminaries including Allan Schore on affect regulation and right-brain development, Diane Poole Heller on attachment and trauma, Louis Cozolino on the neuroscience of psychotherapy, Bonnie Badenoch on presence and the neurobiology of therapeutic relationships, and Pat Ogden on sensorimotor approaches to trauma. This generative capacity, the ability to inspire and organize collaborative work, distinguishes truly transformative thinkers from merely brilliant ones.

Siegel’s institutional leadership includes serving as clinical professor of psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine since 1997, founding co-director of the Mindful Awareness Research Center at UCLA, co-principal investigator of the Center for Culture, Brain and Development at UCLA, and executive director of the Mindsight Institute, an educational organization offering online learning and in-person seminars on mindsight development. He is also co-founder of Mind Your Brain, a Santa Monica-based organization dedicated to bringing kindness, compassion, and resilience into the world through interpersonal neurobiology principles.

He has received numerous honors including Distinguished Fellow of the American Psychiatric Association, multiple honorary fellowships, and UCLA’s teaching award for his work directing the child psychiatry training program. His lectures have reached diverse audiences from neuroscientists to clergy, from corporate leaders to parents, from policy-makers to contemplatives. He has spoken to the King of Thailand, Pope John Paul II, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Google University, and London’s Royal Society of Arts, demonstrating the breadth of interpersonal neurobiology’s applicability.

The integration framework at the heart of Siegel’s work identifies nine domains where linkage of differentiated elements promotes wellbeing. Bilateral integration links left and right hemispheres, allowing logical-linear processing to work harmoniously with holistic-emotional processing. Vertical integration connects cortical regions with subcortical systems including brainstem and limbic areas, linking conscious deliberation with automatic bodily regulation and emotion. Memory integration weaves together implicit memory, the nonconscious influence of past experience on present functioning, with explicit memory, conscious recollection of facts and events.

Narrative integration creates coherent life stories that acknowledge both painful and positive experiences, that recognize continuity of self across time while also allowing growth and change. State integration enables smooth transitions between different modes of consciousness, sleep and wakefulness, focused work and relaxed presence, solitary reflection and social engagement. Temporal integration honors both past and future while remaining grounded in present experience. Interpersonal integration differentiates self from other while maintaining empathic connection, honoring autonomy while cultivating intimacy.

Consciousness integration, cultivated particularly through the Wheel of Awareness practice, links the contents of consciousness with awareness itself, enabling the capacity to observe mental processes without identifying with them. Transpirational integration, perhaps the most controversial domain, involves connection to something larger than the individual self, whether understood as connection to nature, to community, to the flow of generations, or to transcendent dimensions of experience.

Impairment in any integration domain produces characteristic patterns of chaos and rigidity. Lack of bilateral integration may manifest as excessive logic disconnected from emotion or overwhelming emotion disconnected from understanding. Vertical integration deficits create mind-body splits where cortical plans cannot access bodily wisdom or where bodily sensations overwhelm conscious regulation. Memory integration problems produce dissociative symptoms, flashbacks, or inability to learn from experience. Narrative disintegration appears as incoherent life stories, inability to make meaning from experience, or rigid narratives that deny complexity.

From a depth psychology perspective, Siegel’s interpersonal neurobiology provides neurobiological validation for insights Jung articulated phenomenologically. Jung’s emphasis on the transcendent function, the capacity to hold tension between opposites until a third thing emerges, maps directly onto integration as the linkage of differentiated elements. When conscious and unconscious, thinking and feeling, individual and collective can be both distinguished and connected, transformation becomes possible. This requires exactly the kind of observing awareness that mindsight describes, the capacity to hold multiple perspectives simultaneously without collapsing into identification with any single position.

Jung’s concept of individuation, the process of becoming who you truly are, involves integrating previously unconscious or disowned aspects of self. Siegel’s framework suggests this process requires bilateral integration of left-hemisphere understanding with right-hemisphere emotional and somatic knowing, vertical integration of cortical awareness with subcortical drives and affects, memory integration that allows painful past experiences to be processed rather than re-enacted, and narrative integration that creates coherent personal mythology. Individuation, from this view, represents comprehensive integration across all domains.

The shadow, Jung’s term for disowned aspects of personality, forms through lack of integration. When certain emotions, impulses, or characteristics become unacceptable to consciousness, they split off and operate autonomously. Shadow work, the process of recognizing and reclaiming these aspects, requires the mindsight capacity to observe previously invisible material without being overwhelmed by it. The Wheel of Awareness practice, by strengthening the hub of observing consciousness, builds exactly the capacity needed for shadow integration, the ability to see what has been hidden while maintaining enough stability to metabolize the discovery.

Jung emphasized that complexes, emotionally charged networks of associated ideas and memories, possess relative autonomy and can temporarily take over consciousness. Siegel’s understanding of state integration helps explain this phenomenon neurobiologically. Different states of mind involve different patterns of neural activation, different neurochemical milieus, different accessibility to memories and behavioral repertoires. When state shifts occur without integration, when someone moves between modes of functioning without continuity of awareness, the experience closely resembles possession by an autonomous complex. State integration allows different modes to be recognized as aspects of a unified self rather than as foreign intrusions.

Active imagination, Jung’s technique for engaging unconscious material through sustained attention to images and impulses, works through mechanisms Siegel describes. Focused attention on spontaneous mental contents activates neural circuits associated with those contents. Sustained attention strengthens those circuits and their connections to prefrontal integrative regions. The result is increased differentiation, the unconscious material becomes more clearly perceived, and increased linkage, conscious awareness can relate to previously autonomous processes. The neuroplasticity principle, where attention goes neural firing flows and neural connection grows, explains how active imagination produces integration.

For clinicians using interpersonal neurobiology, assessment involves identifying which integration domains are impaired. When a client presents with depression characterized by withdrawal, flattened affect, and inability to experience pleasure, the therapist might recognize deficits in vertical integration, disconnection between subcortical emotional systems and cortical awareness, and state integration, inability to shift between depressed and more vital states. Treatment focuses on building differentiation and linkage in these specific domains through mindsight practices, somatic awareness exercises, and relationship experiences that demonstrate possibility of state shifts.

When working with trauma, interpersonal neurobiology recognizes that traumatic experiences typically overwhelm integrative capacity. The experience fragments into disconnected elements, bodily sensations without narrative context, emotions without understanding, behaviors without conscious choice. Healing requires titrated re-integration, carefully paced exposure to traumatic material while maintaining enough safety and stability that new connections can form. The therapeutic relationship provides external regulation that supports the client’s developing capacity for self-regulation, exactly the function secure attachment serves in childhood.

Couples therapy from an interpersonal neurobiology perspective emphasizes differentiation and linkage in intimate relationships. Healthy partnerships require each person to maintain distinct identity, values, and autonomy while also creating genuine connection through empathic communication and shared experience. Problems arise from insufficient differentiation, where boundaries become blurred and individuality is lost, or insufficient linkage, where autonomy becomes isolation and partners live parallel lives without meaningful connection. The therapeutic work involves helping couples strengthen both differentiation and linkage, creating secure attachment characterized by the dance between closeness and separateness.

Parent-child work focuses on how the caregiver’s own integration or lack thereof shapes the child’s developing capacity for self-regulation. Siegel emphasizes that before worrying about specific parenting techniques, adults need to work on their own mindsight development. Unresolved trauma, rigid narratives, and dissociated emotional experience in parents invariably impact children, as the child’s developing brain picks up on the parent’s internal chaos and rigidity through attunement processes operating largely outside conscious awareness.

Siegel describes a window of tolerance, the zone of arousal within which someone can function effectively. Too much activation pushes the person above the window into hyperarousal, anxiety, panic, or rage. Too little activation drops them below the window into hypoarousal, shutdown, dissociation, or depression. The window’s width varies by person and changes over time. Secure attachment relationships, mindfulness practices, and therapeutic work all expand the window, increasing the range of experience someone can metabolize without dysregulation.

Integration, understood as the fundamental mechanism of expanding the window of tolerance, works by creating more flexible neural networks capable of responding adaptively to wider ranges of stimulation. Differentiated systems can each operate within their optimal zone. Linked systems can draw on each other for support and regulation. The prefrontal cortex, when well-integrated with subcortical regions, can modulate activation levels, applying the brakes when arousal climbs too high and providing gentle acceleration when energy sinks too low.

Critics of interpersonal neurobiology argue that the framework’s breadth makes it difficult to test empirically. Integration as a master principle organizing everything from synaptic function to social systems may be too general to generate specific, falsifiable hypotheses. The concept that mental health reflects integration while mental illness reflects chaos and rigidity provides a compelling narrative but may risk becoming tautological, defining integration as whatever produces wellbeing and wellbeing as whatever results from integration.

Questions remain about whether the specific nine domains of integration Siegel identifies represent truly distinct processes or convenient categories that might be divided differently. The claim that the mind emerges from energy and information flow rather than being synonymous with brain activity, while philosophically interesting, remains challenging to test empirically. How would we demonstrate that relational processes contribute to the mind in ways that go beyond their effects on individual brains?

Siegel’s emphasis on integration as a universal mechanism might underestimate the value of certain forms of differentiation without linkage. Some degree of separation between different aspects of self, some capacity for compartmentalization, may serve adaptive functions. Complete integration of all emotional experience into conscious awareness might overwhelm functional capacity. The unconscious serves purposes beyond storing unprocessed trauma; it allows vast amounts of information processing to occur outside awareness, freeing consciousness for tasks requiring deliberate attention.

The extraordinarily broad synthesis that interpersonal neurobiology attempts, drawing from neuroscience, attachment theory, complexity theory, contemplative traditions, and more, creates both strengths and vulnerabilities. The strength lies in recognizing patterns across levels of analysis, in finding organizing principles that apply from molecules to relationships. The vulnerability involves the risk of using neuroscience to provide false precision to ideas that may be more metaphorical than literal. When Siegel talks about integrating left and right hemispheres, for instance, he refers to functional patterns more than anatomical specifics, but readers may imagine actual neural pathways being built where none exist.

Despite these concerns, interpersonal neurobiology has proven generative clinically and theoretically. Thousands of therapists report that the integration framework helps them assess and intervene more effectively. The mindsight concept gives clients accessible language for understanding their therapeutic work. The Wheel of Awareness provides a structured practice that many find genuinely transformative. The Norton series has produced a substantial body of scholarship applying integration principles to diverse problems and populations.

Siegel’s ability to make complex neuroscience accessible to general audiences, to communicate scientific concepts without oversimplifying, represents a significant contribution in itself. Many brilliant researchers cannot translate their work for broader publics. Many popular psychology writers oversimplify science to the point of distortion. Siegel largely avoids both pitfalls, maintaining scientific rigor while communicating clearly. This has allowed interpersonal neurobiology to influence not only psychotherapy but parenting, education, organizational leadership, and contemplative practice.

The Blue School in New York City built its entire curriculum around Siegel’s mindsight approach, demonstrating how interpersonal neurobiology principles can transform educational practice. Schools using the framework emphasize integration in multiple senses: integrating cognitive, emotional, and social learning; integrating different disciplines; integrating individual development with community building; and teaching children explicit mindsight skills for self-awareness and empathy.

Corporate applications of interpersonal neurobiology focus on how integration principles enhance leadership, collaboration, and organizational health. Leaders who develop mindsight capacity communicate more effectively, make wiser decisions under pressure, and create cultures where diverse perspectives can be both differentiated and linked. Organizations characterized by integration show flexible adaptation to changing circumstances while maintaining coherent identity and values.

For individuals working on their own development outside therapy, Siegel’s work offers accessible practices and conceptual frameworks. The Wheel of Awareness requires no special equipment or training, just willingness to sit quietly and direct attention systematically. The integration concept helps make sense of personal struggles, why certain situations trigger rigidity or chaos, why some relationships drain energy while others generate vitality. Understanding that neural integration is always possible, that where attention goes neural firing flows and neural connection grows, provides hope that change remains possible regardless of past experience.

Siegel emphasizes that neuroplasticity, the brain’s capacity for change, continues throughout the lifespan. While early experience shapes neural development profoundly, particularly during sensitive periods in childhood and adolescence, the brain never stops growing and changing in response to experience. Adult brains can form new neurons, new synapses, new circuits. This means that integration work undertaken at any age can produce genuine transformation, that histories of trauma or impaired attachment do not determine futures, that healing remains possible.

The concept of earned secure attachment illustrates this possibility. Research demonstrates that individuals who experienced insecure attachment in childhood can develop secure attachment patterns in adulthood through therapeutic relationships, secure romantic partnerships, or sustained contemplative practice. These earned secure adults show attachment patterns indistinguishable from those who experienced secure attachment from birth. The key appears to be narrative coherence about attachment experiences, the ability to reflect on early relationships with balance and integration, acknowledging both pain and growth, understanding how past shapes present without being imprisoned by it.

Siegel’s definition of the mind as an emergent self-organizing embodied and relational process that regulates the flow of energy and information provides a foundation for understanding how therapeutic change occurs. If the mind emerges from energy and information flow patterns, then changing those patterns changes the mind. Focused attention, the core mindsight practice, directly modulates energy and information flow. Where we direct attention determines which circuits activate, which connections strengthen, which patterns become habitual.

This has implications for understanding consciousness and free will. If focused attention shapes neural structure, and neural structure shapes subsequent attention patterns, then a recursive loop exists where minds participate in their own creation. We are not entirely determined by genes and early experience, nor entirely free to be whatever we choose, but rather engaged in ongoing co-creation of who we become through how we direct awareness moment by moment. This view preserves agency while acknowledging constraint, honoring both determination and freedom.

For depth psychology practitioners, Siegel provides a contemporary neuroscience framework that validates and extends Jungian insights. The collective unconscious, understood as shared patterns of human experience rooted in our evolutionary heritage, finds expression through subcortical neural systems we all share, ancient circuits for fear, attachment, sexuality, aggression, and nurturance shaped by millions of years of natural selection. Archetypes represent organizing patterns in these shared systems, templates that structure experience in recognizable ways across cultures and eras.

The personal unconscious, unique to each individual based on specific life experiences, involves implicit memory systems that operate outside awareness but shape present functioning. Complexes arise where traumatic or emotionally overwhelming experiences remain unintegrated, operating autonomously because they never became linked to conscious narrative and prefrontal regulation. Dream work accesses this material by attending to the spontaneous imagery produced when prefrontal control relaxes during sleep, providing glimpses of unconscious processing that can then be integrated through reflection and active imagination.

Siegel’s emphasis on both differentiation and linkage captures something essential about psychological health that either extreme alone misses. Pure differentiation without linkage creates isolated fragments, the rigid separations characteristic of obsessive-compulsive patterns or schizoid withdrawal. Pure linkage without differentiation creates chaotic blending, the boundary dissolution seen in borderline patterns or psychotic episodes. Health requires the dynamic balance between honoring distinctions and creating connections, a balance that shifts flexibly across contexts and relationships.

His work suggests that this integration principle applies at every scale. Individual neurons must maintain distinct identities while linking through synapses. Neural networks must differentiate into specialized modules while linking through association fibers. Brain regions must develop unique functions while communicating through white matter tracts. Individuals must cultivate authentic selves while connecting empathically with others. Communities must honor diversity while creating coherent shared narratives and values. The fractal quality of this pattern, appearing at scales from cellular to civilizational, suggests something fundamental about how complex adaptive systems function.

Siegel continues actively teaching, writing, and developing interpersonal neurobiology. Recent work explores how the framework can address collective challenges including polarization, environmental crisis, and social justice. He argues that the same integration principles that promote individual mental health apply to healing societal divisions. Differentiation honors diverse perspectives, lived experiences, and cultural identities. Linkage creates empathic connection across difference. Integration allows communities to value pluralism while maintaining enough coherence for collective action.

The Garrison Institute, where Siegel serves on the board of trustees, applies contemplative practices and interpersonal neurobiology to supporting educators, clinicians, and activists working for social change. The work recognizes that sustainable activism requires practitioners who can maintain their own integration, who can hold intense awareness of suffering and injustice without burning out or shutting down, who can engage conflict without becoming rigid or chaotic.

What Siegel has accomplished most fundamentally involves creating a shared language and framework that allows diverse disciplines and therapeutic approaches to communicate with each other. Before interpersonal neurobiology, attachment researchers, neuroscientists, trauma specialists, mindfulness teachers, and psychodynamic therapists often worked in isolation, each with valuable insights but limited ability to learn from the others. By identifying integration as a common principle, by showing how different approaches address similar underlying processes, Siegel built bridges that enrich all these fields.

Whether interpersonal neurobiology will ultimately be remembered as a distinct theoretical school or as a synthesizing framework that helped existing approaches communicate more effectively remains to be seen. Siegel himself emphasizes that the field is transdisciplinary rather than interdisciplinary, not merely combining existing disciplines but finding organizing principles that transcend disciplinary boundaries. This ambitious vision suggests interpersonal neurobiology aspires to transform how we understand minds, relationships, and healing at the most fundamental level.

For clinicians, the integration framework provides practical guidance for assessment and intervention. For researchers, it generates hypotheses about mechanisms underlying diverse phenomena. For individuals seeking personal growth, it offers accessible practices and empowering insights. For culture more broadly, it articulates a vision of human flourishing grounded in scientific understanding yet open to mystery, honoring both empirical rigor and contemplative wisdom. This capacity to bridge seemingly incompatible domains may represent Siegel’s most enduring contribution to our understanding of what minds are and how they can heal.

Timeline of Daniel Siegel’s Career and Major Publications

1957: Born July 17 in Los Angeles, California

1983: Received medical degree from Harvard Medical School

1983-1987: Postgraduate medical education at UCLA in pediatrics and psychiatry

1987-1989: Served as NIMH Research Fellow studying attachment and family interactions

1997: Joined UCLA School of Medicine faculty as clinical professor of psychiatry

1999: Published The Developing Mind, formally introducing interpersonal neurobiology

1999: Established Center for Human Development (later became Mindsight Institute)

2000: Founded Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology as founding editor

2004: Founded Mindful Awareness Research Center at UCLA as co-director

2003: Published Parenting from the Inside Out with Mary Hartzell

2007: Published The Mindful Brain

2010: Published Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation

2010: Published The Mindful Therapist

2011: Published The Whole-Brain Child with Tina Payne Bryson (New York Times bestseller)

2012: Published second edition of The Developing Mind incorporating 1,000+ new citations

2012: Published Pocket Guide to Interpersonal Neurobiology

2013: Published Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain (New York Times bestseller)

2014: Published No-Drama Discipline with Tina Payne Bryson (New York Times bestseller)

2017: Published Mind: A Journey to the Heart of Being Human (New York Times bestseller)

2018: Published Aware: The Science and Practice of Presence (New York Times bestseller)

2018: Published The Yes Brain with Tina Payne Bryson

2020: Published third edition of The Developing Mind

2023: Published IntraConnected: MWe (Me + We) as the Integration of Self, Identity, and Belonging

Current: Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at UCLA; Executive Director of Mindsight Institute; Founding Co-Director of Mindful Awareness Research Center; Founding Editor of Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology

Complete Bibliography of Major Works by Daniel Siegel

Siegel, D.J. (1999). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. New York: Guilford Press.

Siegel, D.J., & Hartzell, M. (2003). Parenting from the Inside Out: How a Deeper Self-Understanding Can Help You Raise Children Who Thrive. New York: Tarcher/Penguin.

Siegel, D.J., & Solomon, M., eds. (2003). Healing Trauma: Attachment, Mind, Body and Brain. New York: W.W. Norton.

Siegel, D.J. (2007). The Mindful Brain: Reflection and Attunement in the Cultivation of Well-Being. New York: W.W. Norton.

Siegel, D.J., Fosha, D., & Solomon, M., eds. (2009). The Healing Power of Emotion: Affective Neuroscience, Development & Clinical Practice. New York: W.W. Norton.

Siegel, D.J. (2010). Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation. New York: Bantam.

Siegel, D.J. (2010). The Mindful Therapist: A Clinician’s Guide to Mindsight and Neural Integration. New York: W.W. Norton.

Siegel, D.J., & Bryson, T.P. (2011). The Whole-Brain Child: 12 Revolutionary Strategies to Nurture Your Child’s Developing Mind. New York: Bantam.

Siegel, D.J. (2012). Pocket Guide to Interpersonal Neurobiology: An Integrative Handbook of the Mind. New York: W.W. Norton.

Siegel, D.J. (2012). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are, Second Edition. New York: Guilford Press.

Siegel, D.J. (2013). Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain. New York: Tarcher/Penguin.

Siegel, D.J., & Bryson, T.P. (2014). No-Drama Discipline: The Whole-Brain Way to Calm the Chaos and Nurture Your Child’s Developing Mind. New York: Bantam.

Siegel, D.J. (2017). Mind: A Journey to the Heart of Being Human. New York: W.W. Norton.

Siegel, D.J. (2018). Aware: The Science and Practice of Presence. New York: Tarcher/Penguin.

Siegel, D.J., & Bryson, T.P. (2018). The Yes Brain: How to Cultivate Courage, Curiosity, and Resilience in Your Child. New York: Bantam.

Siegel, D.J. (2020). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are, Third Edition. New York: Guilford Press.

Siegel, D.J. (2023). IntraConnected: MWe (Me + We) as the Integration of Self, Identity, and Belonging. New York: W.W. Norton.

Key Academic Papers:

Siegel, D.J. (2001). Toward an interpersonal neurobiology of the developing mind: Attachment relationships, mindsight, and neural integration. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22(1-2), 67-94.

Influences and Legacy

Siegel’s work synthesizes contributions from attachment researchers John Bowlby and Mary Main, whose Adult Attachment Interview methodology provided tools for assessing narrative coherence. Neuroscientist Allan Schore’s research on right-brain affect regulation and orbitofrontal development informed Siegel’s understanding of how attachment shapes neural structure. Antonio Damasio’s work on emotion, consciousness, and somatic markers demonstrated the embodied nature of mind.

Memory researchers Endel Tulving and Robert Bjork contributed understanding of how different memory systems operate. Developmental psychologists including Daniel Stern explored how the self develops through interpersonal relationships. Complexity theorists provided frameworks for understanding emergence and self-organization. Contemplative traditions including Buddhism offered practices and insights about the nature of mind and consciousness.

Siegel has profoundly influenced contemporary psychotherapy through both his writings and the Norton series he edits. Trauma therapists integrate mindsight practices into Somatic Experiencing, EMDR, and Sensorimotor Psychotherapy. Attachment-focused clinicians use interpersonal neurobiology frameworks to understand how early relationships shape neural development. Couples therapists apply differentiation and linkage concepts to help partners create secure attachments.

Mindfulness teachers reference the Wheel of Awareness as a structured practice that systematically cultivates integration. Educators incorporate mindsight development into curricula, teaching children explicit skills for self-awareness, emotion regulation, and empathy. Organizational consultants apply integration principles to leadership development and team effectiveness. The breadth of influence demonstrates how a truly integrative framework can transform multiple fields simultaneously.

Siegel’s accessible communication style, ability to translate neuroscience for general audiences while maintaining scientific rigor, has made interpersonal neurobiology one of the most widely recognized frameworks in contemporary psychology. His five New York Times bestsellers reached millions of readers, while the professional series influenced thousands of clinicians and researchers. This dual impact, shaping both popular understanding and professional practice, positions Siegel among the most influential psychological thinkers of his generation.

For depth psychology, Siegel provides what Jung lacked: empirical grounding for phenomenological insights. Jung’s observations about how unconscious processes operate, how complexes possess relative autonomy, how individuation requires integration of opposites, all find validation and extension through interpersonal neurobiology. The framework demonstrates how ancient contemplative practices and modern neuroscience converge on similar truths about the nature of mind and the path to wholeness.

0 Comments