In 1961, Stanley Milgram conducted an experiment that would fundamentally challenge our understanding of human obedience and moral authority. Participants were instructed by a man in a white coat, an apparent authority figure, to administer what they believed were increasingly harmful electric shocks to another person. The instructions escalated from causing minor discomfort to what participants believed would end the person’s life. Most participants completed the entire sequence. The experiment was ostensibly designed to test whether something like Nazi Germany could happen anywhere, and that became the primary way it was publicized. However, the findings revealed far more complex and disturbing patterns about human nature and institutional authority.

The original study (Milgram, 1963) found that 65% of participants continued to the maximum 450-volt level, despite hearing screams of pain and pleas to stop. But later replications and variations revealed additional troubling findings. When participants were asked to administer shocks to animals rather than humans who were begging them to stop, most people refused to harm the animal while they would harm the human. When the experiment was replicated in Germany, which was supposedly the point of proving that Nazis could happen anywhere, more participants were willing to complete the lethal sequence than in other countries (Mantell, 1971).

Subsequent replications uncovered even more nuanced findings. Burger’s 2009 partial replication found that 70% of participants continued past the 150-volt point where the learner first protests, nearly identical to Milgram’s original findings despite decades of supposed ethical progress. The proximity of the victim mattered significantly: when the learner was in the same room, compliance dropped to 40%, and when participants had to physically place the learner’s hand on a shock plate, only 30% complied (Milgram, 1974). Perhaps most disturbingly, the Hofling hospital experiment (Hofling et al., 1966) extended these findings to real-world medical settings, where 21 of 22 nurses administered what they believed was a dangerous overdose of medication when ordered by an unknown doctor over the phone.

These experiments are a vital parable for the field of psychotherapy. We, too, have our “white coats”: the institutions of “Evidence-Based Practice” (EBP), the diagnostic authority of the DSM, and the seemingly impenetrable paywalls of academic journals. We are facing a fundamental tension between our models and the living reality of our patients, and many practitioners, trained to obey the “protocol,” are discovering that the models themselves are flawed.

The Crisis of “Evidence”

When I first started practicing as a psychotherapist, I was deeply insecure that I wouldn’t know enough, so I studied every model of psychotherapy that had ever been written, to my knowledge. This sounds like an exaggeration, but I had four years to do this while working as an outreach social worker, spending 90% of my time in my car, so I listened to audiobooks on literally everything. The soft science, the weird science, the French science. I thought I was a CBT social worker because that was what we were always told in graduate school was the gold standard that everyone had to start with. This was twenty years ago, but that was what was taught at the time.

One of the trends at the time was EMDR, and The Body Keeps the Score was just coming out and becoming a major best seller. I thought EMDR sounded hokey, but I wanted to try it and thought it might give me a market advantage if I got the training. To date, EMDR has done nothing for me as a patient. I did see it work for many dissociative and severely traumatized patients though. There were also many patients that EMDR did not work for, and I started trying to figure out which type of patients it worked for. Many of them had dissociative experiences relating to trauma or emotion. I saw it work miracles for some of these people and started wondering why. At the time, most researchers thought anyone doing EMDR was either stupid, part of a cult, or that clinical practitioners didn’t know how to read research like informed researchers did.

In my experience, the EMDR clinicians didn’t do themselves any favors. It was often EMDR that had healed these clinicians and it made them true believers, and to be fair, EMDR can work miracles for people who have been stuck in CBT, DBT, IOPs, and ACT therapy for years without progress. Then suddenly something hits them and they realize this emotional part they need to integrate is their job, not something to talk about, not something for somebody else to tell them how to do, but something they can do themselves. I’ve seen it work miraculously, but it doesn’t work for most people. The clinicians usually were somebody who got better through EMDR and became true believers, so they weren’t noticing that 70% of their patients were leaving feeling like it was hokey. The problem is that while EMDR works for about 30% of people in my experience, doing nothing for the 70% who still need help, those 70% still need help and we need to recognize that EMDR isn’t providing it.

Researchers continued to find EMDR slightly less effective or slightly more effective than placebo and thus clinically useless. Clinicians found it was this miraculous technique they were chasing, sometimes coming off as cultish. The researchers thought the clinicians were stupid because they didn’t know how to read research, and the clinicians thought the researchers were stupid because they weren’t paying attention to what happens when you deal with seriously sick people in the room, not calling yourself a clinician because you work three or four days a week at a student counseling center seeing students who broke up with their boyfriend and then providing them with CBT and psychoeducation.

To be clear, when I say that EMDR worked for some patients I don’t mean that I did EMDR while doing other kinds of therapy and symptoms resolved. I don’t mean that I did EMDR once or twice and the patient later got better so I assumed EMDR had something to do with it. I saw what the people that were doing EMDR were seeing. I saw the information that a qualitative research study or a RCT could not capture. I saw around 30% of PTSD patients have a strong and unexplainable, sometimes overwhelming, re-experience and resolution of trauma symptoms every time that they did EMDR. To a clinician, this is the data. This is the starting point of science. A replicable, profound phenomenon is an observation that demands a hypothesis. To a researcher doing a large study, however, this is insignificant because something that works for 30% of patients is within the placebo effect of 35%. They are not asking the right question—”Who is this 30% and why does this work so miraculously for them?”—they are simply discarding the data. We simply cannot research therapy the same way we can research cancer drugs or antibiotics.

The Discovery of Something New

When I was doing EMDR, I started noticing that patients pupil would stop in certain spots and then the pupil would sometimes wibble or go in and out. Sometimes the pupil itself would avoid one of the places on the EMDR tracking line when a patient was trying to follow my fingers. These responses weren’t conscious; they happened before a patient could be aware of it, and people don’t have micro control over their pupil dilation and the way the eye moves in the room when it’s trying to move really fast. They were replicable, and I started to stop in the spot where I saw a pupil either moving or jumping around. When I stopped in these spots, I saw people go into deep and profound states of processing, and then patients started often requesting that I do that instead of the normal EMDR protocol. When I did, they experienced rapid resolution and relief.

The EMDR trainers and consultants were no help because I requested more and more consultations and kept hearing the same thing. They would tell me I needed to do the 15 movements or 25 or whatever protocol because Francine Shapiro had said it and that was the protocol. But what if you see a DID patient who’s gone into an alter? What if you see a person who has completely decompensated? These protocols weren’t flexible, and the EMDR clinicians were tied to them. The trainers and advanced specialists couldn’t really think outside of the box.

Eventually I spoke to a colleague who told me this sounded a lot like brain spotting. I didn’t know what that was, so I bought the book and read it, but it didn’t contain anything I was seeing. So I paid $400 an hour to talk to David Grand, who is the founder of Brainspotting, because I had been a clinician for three months at this point and was seeing things I couldn’t explain that no one was able to help me with. Dr. David Grand told me he was a pupil of Francine Shapiro, founder of EMDR, and that he had invented brain spotting when he saw the same thing I did. He encouraged me to get the training so I would understand what it felt like. He told me I was doing it but didn’t know what it felt like, and that was a missing part. To date, ten years later, this has always been a foundation of my approach.

I integrate many different types of psychotherapy into my practice, but getting the training is the smallest part of your education. You need to read all the books of the founders and understand their thought process, and most importantly, you need to do the actual therapy yourself. It’s not the “ah” of learning, it’s the “ah ha” of experiencing. When I got my comparative religion degree, we used to talk about the “ah” being understanding a religion or ritual intellectually and the “ah ha” as being the felt experience of being effected by the metaphors and psychological process of the content. These rituals and experiences are something people do because they mean something and contain symbolic and metaphorical power. Understanding them is half of the technique; feeling it is the other half.

Brain spotting lets clinicians target traumatic experiences more surgically than EMDR because it allows them to stop on one spot and let a client go all the way through one part of memory instead of activating all the little bits of memory and trying to reconsolidate them in the room. In my opinion Brainspotiing works much faster than EMDR, more thoroughly and has less risk of decompensation for the patient. However, it took Francine Shapiro inventing EMDR for other people to build on her work, even though research was always going to find an approach like that mostly ineffective. Now, because of massive meta-analyses and the Veterans Administration, we know that EMDR is effective and it’s been broadly accepted as an effective psychotherapeutic practice. But this reveals the core crisis: by the time the ‘white coats’ finally approve a 1987 discovery, the most innovative practitioners are already three models ahead. We are validating the past while innovation is forced to operate, by necessity, without a map. Brainspotting and Emotional Transformation Therapy have replaced it for my in my practice in Hoover Alabama. By the time research got around to validating something invented in 1987 and it trickled through colleges so people shouldn’t recoil in horror when somebody was doing something new and weird, that thing was already not the most useful thing we could be doing with patients.

The “Evidence-Based” Fallacy and Flawed Research

When I started to talk to the EMDR experts about the innovations I was making, I discovered a fundamental tension. It seemed that many therapists felt that it violated evidence-based practice paradigms to change or innovate on these models. They felt that the old models had been researched and could not be changed. This was the case whether or not those models actually did have a basis in research, and many of them didn’t. It was also the case even when the clinicians would admit to adding and innovating on their model under names other than innovation or change.

Of course, clinicians should be prudent and trained, but following consistently reproducible phenomena in therapy is the basis of every model of therapy. Nothing comes into existence already backed by research. Clinicians create models in psychotherapeutic practice, not in laboratories on rats. Only then can research validate the model. I was discovering that many people who think they are beholden to research fundamentally do not understand what its role is or how it works. Many of these therapists just had an affinity for rules and hierarchies but could poorly explain or understand the incentives and realities of actual academic research. These clinicians were just predisposed emotionally to side with authority structures.

The scientific method starts with a hypothesis and then small empirical observations, and that is the beginning of all therapy models. Research does not create innovation. Research measures how effective innovation is. Therapists create innovation when others’ insecurities and neuroses, often disguised as caution or diligence, get out of their way.

Cognitive and behavioral therapy often misses these patterns because it maintains a surface-level focus on conscious thoughts and behaviors without exploring the unconscious emotional narratives that drive them. From a psychodynamic perspective, this is a key limitation, as CBT tends to treat distorted thoughts as direct causes of symptoms, whereas psychodynamic models often view them as manifestations of deeper, underlying conflicts. CBT also assumes conscious consent, meaning it presumes patients are aware of their emotional patterns and can rationally address them, when in reality these patterns operate outside conscious awareness. This aligns with critiques from many of the field’s most important thinkers, from Bessel van der Kolk’s work on the body to Drew Westen’s critique of “evidence” to Jonathan Shedler’s argument that the premise of many “evidence-based” therapies underestimates the complexity of the unconscious mind and that their benefits often do not last (Shedler, 2018).

In many research papers I read that validated CBT as evidence-based, I observed that participants had left the study because they felt the CBT therapy was not helpful. These participants were removed from the study as having failed to complete treatment. However, these studies still found that CBT was “highly effective” using the remaining compliant participants. No one was left in the study who had the self-awareness to say that the therapy was not helpful or had the intuition to follow their gut. This is my observation from reading these studies. Research that only measures progress toward the goal someone had before therapy is blind in one eye because effective therapy reveals new goals to patients all the time as they get better.

The debate about whether CBT’s effectiveness is declining illustrates these problems perfectly. A 2015 meta-analysis by Johnsen and Friborg found that CBT’s effectiveness appeared to be declining over time. A subsequent re-analysis by Cristea and colleagues in 2017 identified methodological concerns and concluded that the apparent decline may be a spurious finding. This debate highlights the complexity of interpreting psychotherapy research. But it also reveals a profound hypocrisy. For decades, the EBP movement has dismissed psychodynamic, humanistic, and somatic therapies for lacking quantitative RCT data. Yet when a large, quantitative meta-analysis turned against their “gold standard,” its defenders suddenly became experts in qualitative nuance, citing “methodological concerns” and “therapist allegiance”—the very “anecdotal” arguments they forbid other models from using as evidence. Importantly, these comparisons typically focus on CBT, DBT, and psychodynamic therapies. They don’t examine modern somatic approaches like brainspotting, ETT, or parts-based therapies like Internal Family Systems, which limits the scope of these analyses.

The controversy reveals a profound irony. The push to label formulaic and manualized approaches as “evidence-based” was driven by a researcher-centric view that favored the methodological purity of RCTs, a preference not always shared by clinicians or patients. As Shedler (2018) argues, the demand to exclude non-RCT data inadvertently proves the point made by critics of the EBP movement: by elevating RCTs as the only legitimate form of evidence, the field risks ignoring a wealth of clinical data and creating a definition of “evidence” that does not reflect the complex, comorbid reality of actual clinical practice (Westen et al., 2004).

In my mind, what is more likely than placebo effects or incompetence is that the early effectiveness of CBT relied on all of the other skills clinicians of the 1960s and 1970s were trained in. As these clinicians trained in psychodynamic, relational therapy, depth psychology, and Adlerian techniques left the profession, then pure CBT was left to stand on its own merits. This would explain a completely linear decline in effectiveness found in the 2015 Johnsen and Friborg meta-analysis. Older clinicians retire each year and take the skills that are no longer taught in colleges with them. Any decline in efficacy we are seeing could result from clinicians doing CBT who have been taught only cognitive and behavioral models in school. This is my hypothesis based on observing the field over time. The decline in broader psychotherapeutic training is well-documented; by the mid-2010s, over half of U.S. psychiatrists no longer practiced any psychotherapy at all (Tadmon & Olfson, 2022), a stark contrast to previous generations.

The Rot at the Core: The STARD Scandal

For decades, psychotherapy has walked a tightrope between the worlds of scientific research and clinical practice. Many well-meaning therapists, in an earnest attempt to be responsible practitioners, cleave to the research literature like scripture. But the very research we rely on can be flawed, biased, or outright fraudulent. Peer review is supposed to ensure quality control, but turning public colleges into for-profit entities has meant that publication incentives reward career and financial interests and cast doubt on the reliability of even the most prestigious publications. This critique is powerfully supported by figures like Irving Kirsch, whose work reveals that for many, antidepressants are only marginally more effective than a placebo.

The STARD study provides a stark reminder of these risks. This influential study, published in 2006 (Rush et al., 2006), appeared to show that nearly 70% of depressed patients would achieve remission if they simply cycled through different antidepressants in combination with cognitive-behavioral therapy. Guided by these findings, countless psychiatrists and therapists dutifully switched their non-responsive patients from one drug to the next, chasing an elusive promise of relief. But as a shocking re-analysis has revealed (Pigott et al., 2023), the STARD results were dramatically inflated through a combination of scientific misconduct and questionable research practices.

The forensic re-analysis systematically exposed the extent of these issues. The widely publicized 67% cumulative remission rate was not based on the study’s pre-specified, blinded primary outcome measure (the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression). Instead, investigators switched to a secondary, unblinded, self-report questionnaire (the QIDS-SR) which showed a more favorable result. When the correct primary outcome measure is used and all participants are properly included, the cumulative remission rate is only 35%. Notice that number? It’s the same 35% placebo rate that researchers used to dismiss EMDR’s 30% “miracle” subgroup. This statistical inflation was compounded by other protocol violations, including the exclusion of hundreds of patients who dropped out and the inclusion of over 900 patients who did not meet the study’s minimum depression severity for entry.

Perhaps most damning, the 67% figure refers only to achieving remission at some point during acute treatment and completely obscures the rate of sustained recovery. The re-analysis found that of the original 4,041 patients who entered the trial, only a small fraction achieved lasting positive outcome. When accounting for dropouts and relapses over the one-year follow-up period, a mere 108 patients, just 2.7% of the initial cohort, achieved remission and stayed well without relapsing. For seventeen years, the false promise of the STARD findings guided the treatment of millions, subjecting patients to numerous medication trials based on fundamentally unsound research.

How could such a house of cards have stood unchallenged for so long? Part of the answer lies in the cozy relationship between academic psychiatry and the pharmaceutical industry. The lead STAR*D investigators had extensive financial ties to the manufacturers of the very drugs they were testing. These conflicts of interest, subtly or not so subtly, shape what questions get asked, what outcomes are measured, and what results see the light of day. As Angell (2009) argues, these conflicts create powerful incentives to compromise the trustworthiness of the work.

The Anti-Scientific Foundation: The DSM

The profit motive and this lack of trust hurt clinical practice and stifle new ideas. This flawed thinking is embedded in our most basic tools, especially the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The DSM is built on the idea that clustering symptoms together creates a new, independent, self-evidencing entity called a “diagnosis.” This is a profoundly anti-scientific methodology that is, at its core, a flawed concept. The system defines “objectivity” as adherence to its own instruments, a tautology that mistakes the map for the territory.

Many times people email me because I like Jungian phenomenology and tell me that the ideas of archetypes in Jungian psychology cannot be evidence-based because they are not falsifiable. How is the idea that clustering symptoms together results in a new thing that we should treat like an independent entity called a diagnosis not a non-falsifiable idea also? You literally have to take on faith that these diagnoses are real to research them so how could one disprove them in the current system. Please don’t email me and tell me a council of psychiatrists updates the ideas in the DSM every few years based on the assumptions within the DSM so that makes it a falsifiable and scientific postulate. Just don’t even waste time typing that out.

I use the DSM in practice daily. I don’t think we should get rid of it. I think we should treat it as what it is and have forgotten. It is an idea. The diagnosis with in it are ideas. They are LENSES FOR INQUIRY, not objective realities. Modern research has mistaken the reflection for the object and the map for the territory. How did the entire industry get there? It seems like a much LESS evidence-based idea on its face than that the ideas in perennial philosophy that keep-occurring across culture and time with no cross-influence might be relevant to psychology. How is the DSM system of differential diagnosis itself scientific at all? Shouldn’t you look at processes in the brain and what they are doing instead of lists of behaviors?

The objectivity these people expect you to have for symptom-based diagnostic clusters means that you have to take the following ideas seriously. In medicine, you have a specific type of cancer if you have cells growing in a tumor that meet that criteria. You have a strep infection if the masses of bacteria inflaming your throat are of the streptococcus strain. These are objective, real, uni-causal things. To take the DSM as seriously as an “objective metric,” you have to believe that a child having temper tantrums is as uni-causal and similarly self-evidencing as strep or cancer. Ask yourself if you can really do that as a serious person.

Look at Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD). Proponents define it as a childhood mood disorder characterized by severe, chronic irritability and frequent, intense temper outbursts that are significantly more severe than typical tantrums. They emphasize that DMDD identifies a specific group of children whose symptoms are extreme and persistent, causing significant impairment and requiring symptoms to be present for at least a year. But this definition is the problem. This is a “diagnosis of convenience,” created because the system needs a billable, medical-sounding label for a population it is otherwise failing to treat. It is not a scientific idea. It is a tautology: the diagnosis is the list of symptoms. The system cannot be disproven because it doesn’t propose anything other than its own categories, and it makes the real processes we should be talking about—family systems, material environment, parenting, or underlying neurodivergence like autism—invisible, because those things are messy, hard to “fix,” and don’t fit the simple, uni-causal model.

This focus on symptom clusters is a failure. As Thomas Szasz (1960) argued, psychiatry’s biomedical model falsely equates problems in living with medical diseases. He wrote that calling a person “mentally ill” does not identify a biological cause but rather describes behavior that society finds troubling. This confusion turns descriptions into explanations, a logical error that obscures the real psychological or social roots of distress. As Deacon (2013) documents, the biomedical model has dominated psychiatric thinking, yet paradoxically this period has been characterized by a broad lack of clinical innovation and poor mental health outcomes.

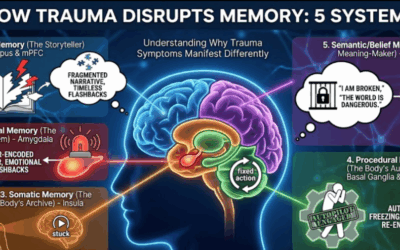

This means that people diagnosed with the same disorder are not receiving the help they need because we are not actually diagnosing what is wrong with them. We are cataloging their observable distress and assuming that similar presentations indicate similar dysfunctions. The profession cannot afford this assumption anymore. We need diagnostic frameworks that describe actual brain processes, like blocked hierarchical processing or “failed prediction error minimization” (ideas being explored by thinkers like Karl Friston). We need language that captures processes, not just presentations.

The Biomedical Bluff: The qEEG Test

This brings us to the system’s great, unacknowledged hypocrisy. If you really wanted to do the biomedical model well, you would demand biological proof. If these are brain-based “disorders,” then we should be required to find their biological markers. Every client file should open with a qEEG brain map or fMRI scan. We should be describing dysfunction in terms of actual, objective brain metrics and processes, not just subjective 19th-century checklists.

But the “white coats” don’t want to do that. They fear it, and they don’t want to pay for it. Checklists are cheap; brain maps are expensive. More importantly, they fear the data. The moment they run a qEEG, they might find that the “DMDD” brain’s biomarkers look identical to the “Autism” brain or the “C-PTSD” brain, and the entire DSM—their sacred text—would be revealed as the house of cards it is. They cling to their symptom checklists because they are not engaged in a scientific pursuit. They are protecting an institution. This is why clinical subjectivity—the ‘high trust’ observation of what is happening in the room—is not ‘anti-science.’ It is the only real science left in a field that is terrified of its own data.

The Profit Motive: Academic Publishing as Extortion

This chilling effect on science is institutionalized by the academic publishing industry. Look at the landscape. There is a trend of academic publishers getting bought up by for-profit industries. These companies are the most profitable on earth. They make more money than Google, and for what? For hosting something on a server and charging universities obscene amounts per student or faculty to be able to access it. Wouldn’t this be better accomplished by Google Drive?

Some of my favorite researchers in somatic and Jungian psychology still thought this old method was the way: get a PhD and publish research in academic journals. But sadly, few people except myself will ever read it. My blog has a larger readership than some of these publications. What do these companies provide or create at all? They are mandatory paywalls that hurt everyone and make the entire landscape worse and the entire field less scientific. Why are researchers and clinicians not given ownership of their work or the ability to profit from it? Why is there a mandatory middleman that researchers have to get extorted by? What would putting an academic journal on a server for free not accomplish that these “publishers” benefit from? They are sitting there asking universities to pay them so you can read research that much of the time your own government or DARPA paid for anyway. WHY?

The Human Cost: Sunk Cost Fallacies and Double Binds

But here is the thing: the smart people in the industry already know this. I hear from them. I talk to them: therapists, researchers, neurologists, MDs.

Sure, there are many people that have participated in this system long enough that the sunk cost fallacy means that they will never be able to criticize it because they can’t see the horror of the waste in their own life. These people are limited by their own imagination and will defend the system as the “way it has always been” (false) and the “way it has to be” (false) or “the only way we can be safe and ethical” (again, false). When you encounter people like this, they will write you long emails or Reddit PMs explaining HOW the system works, as if fetishizing a process is somehow an explanation or a defense. “Well you see there are H-Indexes and impact factors and you have to…”

But this is a response without an argument. A detailed explanation of how a corrupt system functions is not a justification for its existence. If your only argument is that you know how it works, then anyone else who knows how it works can also tell you that it shouldn’t exist. I do not critique this system because I don’t understand it; I critique it because I do, and I refuse to accept that its self-sealing logic is a substitute for results. What I am saying is that the research establishment has become an INCENTIVE STRUCTURE where science itself is disincentivized and bad process and lack of discovery are incentivized.

People who point out and critique the system are often accused of being idealists, but far from it. They are the only realists practicing psychology today. Realism means that you are willing to recognize inevitabilities in systems. You aren’t more wise or mature because you pretend that detrimental systems are actually good. There is a need to be upset. If you are not upset by this, you are willfully ignorant because these things are too scary for you. Have fun being calmer than me; it doesn’t make you more correct.

The OTHER half of the therapists, MDs, and researchers I hear from are still in the system because they love making good research, doing good therapy, or finding the best practice. They realize the system is broken, but they love what they do, and playing politics is the best way to do as much good as they can. Props to you. But here’s the thing: they all tell me they know that it doesn’t work, and they all tell me that their jobs and careers are contingent on not talking about that very much. They are in the same position that I am in.

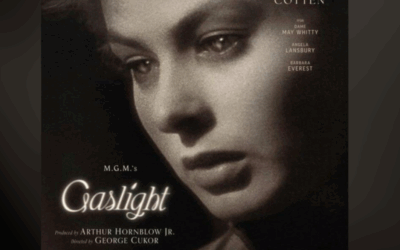

Ronald Fairbairn observed that it is being put in a double bind or a false choice that creates the conditions for trauma. The diagnostic process of the DSM, the way that evidence-based practice is conceived of, and the way that research is funded, evaluated, distributed, and carried out put all of us in that system in a double bind, no matter how much we see it or admit it. It is a system that cannot be indicated no matter how much of a failure that it has become, because its conditions for participation mean that it cannot indict itself. Clinicians know this. Anyone who does effective therapy for a while figures this stuff out.

The Patient’s Double Bind: Why the ‘White Coats’ Are Losing the Trust War

This double bind isn’t just an abstract problem for clinicians; it is being inflicted directly on our patients. The “official” system of mental healthcare is, for many, fundamentally unnavigable and traumatizing in its own right.

Patients are told to seek “evidence-based” help. What do they find? First, they are offered the very “white coat” solutions we’ve critiqued: rigid, manualized CBT that doesn’t touch their underlying pain, or a carousel of medication trials based on the false 2.7% promise of studies like STAR*D. When these “low trust” solutions fail to provide relief, they are told to simply try again.

But the system itself is a logistical trap. They get stuck in endless referral loops. They finally find someone, diligently check their insurance, and think they are covered, only to be traumatized by a surprise bill for $2,000 six months later. They are then told to “simply fill out the paperwork” for reimbursement—a stack of forms so complex and hostile it functions as its own barrier to care, especially for someone already struggling with depression, anxiety, or executive dysfunction.

This bureaucratic, financial, and emotional gauntlet is the patient’s lived experience of “Evidence-Based Practice.”

Then, we see the “white coats” and their defenders in mainstream publications writing articles lamenting that the public is turning to “pseudoscience” and “wellness influencers.” They lecture the public on the dangers of unvetted information and plead for them to “come back to real, evidence-based care.”

But why would they? What the establishment dismisses as “pseudoscience” is often the very same clinician-led, somatic, and process-oriented work (like EMDR or Brainspotting in their early days) that the “white coats” have spent decades dismissing as “anecdotal.”

When the “official” system offers them both clinically ineffective models (as the STAR*D re-analysis and CBT’s decline suggest) and a traumatizing bureaucratic experience, why wouldn’t they turn to something else?

This is the fundamental reality that the establishment refuses to see: People will always trust their own, self-evident “ah-ha” experience over what they are lectured about on the news.

This is not just a professional failure; it is a social imperative. We have to give people something that is self-evidently helpful. If our “Evidence-Based Practice” is not more accessible, more transparent, and more effective in its delivery than the “pseudoscience” we mock, the public will rightfully turn on this profession. We will have failed the Milgram test not by actively inflicting harm, but by standing by a system that does it for us. Our authority will be lost, and we will have deserved to lose it.

The “Low Trust” System vs. “High Trust” Healing

There is an odd phenomenon occurring in psychology right now where soft sciences somehow seem exempt from the scientific method as long as they hold up signifiers and symbols of how it is supposed to work. It has been critiqued as practitioners following capitalism-flavored science instead of natural science.

Theodore Porter’s work in Trust in Numbers reveals why this happens. Porter argues that quantification is fundamentally a “technology of distance.” The language of mathematics is highly structured, and reliance on numbers minimizes the need for intimate knowledge and personal trust. Objectivity derives its impetus from cultural contexts where elites are weak and trust is in short supply.

Porter demonstrates that what we consider “objective” methods in psychology emerged from specific historical conditions rather than representing superior ways of understanding human experience. The drive toward mechanical objectivity arose not as a natural progression but as a response to what he calls “low trust networks,” complex social systems where personal relationships and individual judgment could no longer coordinate social action. When you cannot know your officials personally, when institutions must coordinate the actions of thousands of strangers, mechanical rules and quantitative measures become tools for managing distrust.

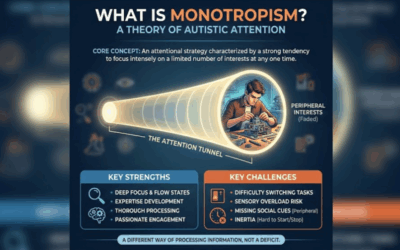

Porter’s critique is essential for understanding emotion because emotions are inherently products of high trust, relational knowing. When psychology attempts to study emotion through the objective, quantitative methods that emerged from low trust institutional networks, it fundamentally misrepresents what emotions actually are. Emotions emerge from the relationship between the experiencing subject and their world. They are not objects that can be studied independently of the subjective experience of having them.

Porter’s analysis helps explain why the increasing dominance of cognitive-behavioral approaches in psychology has actually degraded rather than enhanced our understanding of emotion. CBT represents the triumph of low trust network thinking in therapy: the belief that standardized protocols and measurable outcomes can replace the intimate, relational knowledge required for genuine emotional understanding. In CBT, emotion is recognized, but then managed, labeled and compartmentalized in terms of behavior. It is not seen as a source of authentic wisdom or an indicator that identity should change or intuition should be reclaimed.

When therapy becomes overly focused on objective measurement, standardized protocols, and symptom reductive metrics, it risks reinforcing the very alienation from one’s own subjective experience that often underlies psychological distress. The focus on evidence-based protocols and diagnostic standardization reflects exactly the kind of low trust thinking that Porter identifies: the assumption that mechanical rules can substitute for the nuanced, relational understanding that human emotional life actually requires.

The Path Forward: We Need Trust

We need to trust each other again to be able to collaborate, to share observations, to offend each other occasionally with challenging interpretations, to critically analyze what we see in therapy even when that analysis is weird or uncomfortable or doesn’t fit neatly into approved diagnostic categories. This is what a living profession looks like. A profession that is alive is messy, argumentative, creative, willing to be wrong, excited about new ideas, capable of self-correction. A profession that is risking stagnation is careful, defensive, protocol-driven, afraid of liability, more concerned with not making mistakes than with making discoveries.

Randomized controlled trials and objective research are completely fine if you want to see if a certain type of antibiotic kills one strain of bacteria. When it comes to understanding processes in the deep brain, it does very very little. We have to be able to listen to experiences, to speculate about mechanisms of action. If we can’t do that, we can’t do psychology. The people who I make this argument to often explain to me how the system works. I know how it works. What I’m saying is that it’s bad, and the reason you are defending it is because of the sunk cost fallacy. It shouldn’t work this way. The realists want to be like “well it does,” and if you want to do that, go ahead and do that, but please stop emailing me. Stop telling me that I’m too idealistic for saying that we should listen to self-evidencing things being self-evident and that part of the scientific method is that process, because you have a brain and you cannot bring a hypothesis into a test until you’re able to make one.

Reading research is not simple, but it’s the easiest part of psychology. If I want to get on PsycINFO right now and search for studies and see what the general consensus is, I can do that in under an hour. I can do that as a social worker, and it’s not hard. If you think that’s the hard part, then you’re wrong. The hard part is being able to figure out what those findings mean and apply them to actually change people’s lives, figuring out where they work and where they don’t, not based on research that by the time it gets to you is 15 years old, but based on the mechanisms of action that are part of the narrative of the story that research is telling. If you can’t see the narrative, what you’re doing is just moving beans around, moving beads on an abacus. It’s not ever going to connect to reality. You’ve mistaken the mirror for the object. You’ve mistaken the map for the territory. We have trained a generation of clinicians that can’t think, they can’t understand how somebody else’s experience might be different from their own or why the DSM-5 drawing checkboxes around a group of symptoms might not actually mean that a diagnosis is this thing that exists in reality, just a description of it.

We need processes in psychotherapy again. We need trust. We need to believe our peers when they discover and see something new. We need trust and communication, and an ability to talk about process, not just static checklists. Porter’s analysis shows us that the intimate, relational, meaning-saturated domain of psychotherapy has been colonized by institutional technologies designed for managing distrust. The biomedical model provides the ideological justification for this colonization by recasting psychological suffering as a technical problem amenable to standardized solutions. Yet as therapeutic alliance research demonstrates (Martin et al., 2000), the quality of the human relationship between therapist and patient consistently predicts outcomes across treatment modalities.

This is not a retreat from science; it is a demand for a better one. A true “evidence-based” field would treat systematic clinical case studies as high-level evidence for how change occurs, not just dismiss them as “anecdotes.” It would fund clinicians to run process studies, not just pharmaceutical companies to run RCTs. It would build free, open-source repositories for clinical observation, dismantling the for-profit publishing paywalls that stifle innovation. We do not need to replace the “white coat”; we need to remind the person wearing it that their job is to observe reality, not to command it.

This is not a retreat from science; it is a demand for a better one. A true “evidence-based” field would treat systematic clinical case studies as high-level evidence for how change occurs, not just dismiss them as “anecdotes.” It would fund clinicians to run process studies, not just pharmaceutical companies to run RCTs. It would build free, open-source repositories for clinical observation, dismantling the for-profit publishing paywalls that stifle innovation. We do not need to replace the “white coat”; we need to remind the person wearing it that their job is to observe reality, not to command it.

This critique explicitly includes the hypocrisy of what gets dismissed as “unscientific.” People sometimes email me arguing that Jungian concepts like archetypes cannot be evidence-based because they are not falsifiable. But this critique must be turned back on the DSM itself. How is the DSM’s core assumption—that clustering symptoms creates real, independent diagnostic entities—any more falsifiable than archetypal theory? You literally have to take on faith that these diagnoses are real independent things in order to research them within the current system, so how could one disprove them?

This is why I mention perennial philosophy directly: ideas and patterns that keep recurring across cultures and time with no cross-influence might actually be more relevant to psychology than the DSM’s arbitrary symptom lists. The whole argument is that we’ve mistaken bureaucratic convenience for science. In doing so, we’ve dismissed genuinely phenomenological observations—like Jung’s work on archetypes—as unscientific, while elevating a fundamentally circular and anti-scientific diagnostic system to the status of objective truth.

This creates the double bind for everyone involved. Clinicians are told to be scientific and evidence-based, but the system defining “evidence” excludes the very observations that lead to real therapeutic breakthroughs. For patients, they are told to trust scientific authority, but when the treatments don’t work and they say so, they’re dismissed. As Ronald Fairbairn recognized, being trapped in these impossible, no-win choices is itself traumatizing. That is exactly what the current mental health system does to everyone in it.

References

American Psychological Association. (2006). Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist, 61(4), 271-285. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271

Angell, M. (2009, January 15). Drug companies & doctors: A story of corruption. The New York Review of Books. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2009/01/15/drug-companies-doctorsa-story-of-corruption/

Burger, J. M. (2009). Replicating Milgram: Would people still obey today? American Psychologist, 64(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016234

Cristea, I. A., Stefan, S., Karyotaki, E., David, D., Hollon, S. D., & Cuijpers, P. (2017). The effects of cognitive behavioral therapy are not systematically falling: A revision of Johnsen and Friborg (2015). Psychological Bulletin, 143(3), 326-340. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000062

Deacon, B. J. (2013). The biomedical model of mental disorder: A critical analysis of its validity, utility, and effects on psychotherapy research. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(7), 846-861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.007

Fairbairn, W. R. D. (1952). Psychoanalytic studies of the personality. Tavistock Publications. (Link to summary: https://www.psychoanalysis.org.uk/our-authors-and-theorists/ronald-fairbairn/)

Hofling, C. K., Brotzman, E., Dalrymple, S., Graves, N., & Pierce, C. M. (1966). An experimental study in nurse-physician relationships. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 143(2), 171-180. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-196608000-00008

Johnsen, T. J., & Friborg, O. (2015). The effects of cognitive behavioral therapy as an anti-depressive treatment is falling: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 747-768. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000015

Larivière, V., Haustein, S., & Mongeon, P. (2015). The oligopoly of academic publishers in the digital era. PLOS ONE, 10(6), e0127502. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127502

Lilienfeld, S. O., Ritschel, L. A., Lynn, S. J., Cautin, R. L., & Latzman, R. D. (2014). Why ineffective psychotherapies appear to work: A taxonomy of causes of spurious therapeutic effectiveness. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(4), 355–387. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614535216

Longhofer, J., & Floersch, J. (2014). Values in a world of evidence: A critique of evidence-based practice. Qualitative Social Work, 13(1), 44-62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325012449624

Mantell, D. M. (1im. (1971). The potential for violence in Germany. Journal of Social Issues, 27(4), 101-112. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092849

Martin, D. J., Garske, J. P., & Davis, M. K. (2000). Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 438-450. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-02300-006

Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4), 371-378. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040525

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view. Harper & Row.

Pigott, H. E., Kim, T., Xu, C., Kirsch, I., & Amsterdam, J. D. (2R(203). What are the treatment remission, response and extent of improvement rates after up to four trials of antidepressant therapies in real-world depressed patients? A reanalysis of the STARD study’s patient-level data with fidelity to the original research protocol. BMJ Open, 13(7), e063095. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063095

Porter, T. M. (1995). Trust in numbers: The pursuit of objectivity in science and public life. Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691208411/trust-in-numbers

Rush, A. J., Trivedi, M. H., Wisniewski, S. R., Nierenberg, A. A., et al. (2006). Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: A STARD report. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(11), 1905-1917. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905

Shedler, J. (2018). Where is the evidence for “evidence-based” therapy? Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 41(2), 319-329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2018.02.001

Szasz, T. S. (1960). The myth of mental illness. American Psychologist, 15(2), 113–118. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1960-06322-001

Tadmon, D., & Olfson, M. (2022). Trends in outpatient psychotherapy provision by U.S. psychiatrists: 1996-2019. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 179(2), 110-121. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202100086

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Penguin Books.

Weissman, M. M., Verdeli, H., Gameroff, M. J., Bledsoe, S. E., et al. (2006). National survey of psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(8), 925–934. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.925

Westen, D., Novotny, C. M., & Thompson-Brenner, H. (2004). The empirical status of empirically supported psychotherapies: Assumptions, findings, and reporting in controlled clinical trials. Psychological Bulletin, 130(4), 631-663. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.631

World Conference on Research Integrity. (2010). Singapore statement on research integrity. https://www.wcrif.org/statements/singapore-statement

0 Comments