Why trauma survivors feel “stained” even when nothing physical happened—and how ritual can restore the symbolic order of the self.

The Sensation That Won’t Wash Away

She scrubs her hands until they’re raw. She’s been doing it for months now, ever since the assault. The soap, the hot water, the endless repetition—none of it helps. She knows, intellectually, that she’s not dirty. Nothing visible stains her skin. Yet the sensation persists: a feeling of contamination that no amount of washing can remove.

This is one of the most common and least understood experiences in trauma therapy. Survivors of abuse—sexual, emotional, spiritual—frequently report feeling “dirty,” “stained,” “ruined,” or “contaminated,” even when no physical violation occurred. The soldier with moral injury feels polluted by what he witnessed. The adult child of narcissists feels “tainted” by her upbringing. The survivor of emotional abuse feels like something fundamental has been soiled.

Psychology tends to treat this as a metaphor—the client feels dirty, but isn’t really. Or it’s pathologized as a symptom of PTSD or OCD, to be treated with exposure and response prevention. But what if we’re missing something? What if the sensation of contamination isn’t merely psychological but anthropological—a crisis of symbolic order that requires symbolic restoration?

Enter Mary Douglas, the British anthropologist whose seminal work Purity and Danger revolutionized our understanding of pollution, taboo, and the symbolic boundaries that structure human experience. Her insights offer therapists a powerful new lens for understanding shame, OCD, and the healing power of ritual.

Dirt as “Matter Out of Place”

The Revolution in Understanding Pollution

Before Mary Douglas, scholars assumed that concepts of “clean” and “dirty” were primarily biological—attempts to avoid germs, disease, and physical contamination. Douglas overturned this assumption with a single, elegant insight:

“Dirt is matter out of place.”

This definition transforms our understanding of pollution from a biological category to a symbolic one. Dirt isn’t about germs; it’s about the violation of classificatory systems. Something becomes dirty when it appears where it doesn’t belong.

Consider Douglas’s classic examples:

Shoes on the floor are not dirty. Shoes on the dining table are dirty.

Hair on the head is beautiful. Hair in the soup is revolting.

Soil in the garden is earth. Soil on the kitchen counter is dirt.

The substance itself hasn’t changed. What’s changed is its location relative to a classificatory system. The shoe carries no more germs on the table than on the floor—but on the table, it violates the boundary between “outdoor” and “indoor,” “ground” and “eating surface,” “public” and “intimate.”

“Dirt,” Douglas wrote, “is the by-product of a systematic ordering and classification of matter.” Where there is dirt, there is a system. Where there is pollution, there is an order that has been violated.

The Anomaly and the Threat

Douglas’s insight goes deeper. Dirt isn’t just matter out of place—it’s an anomaly that threatens the coherence of an entire classification system.

Every culture organizes the world into categories: clean/unclean, sacred/profane, inside/outside, self/other. These categories aren’t just intellectual conveniences—they’re the structure of meaning itself. They tell us what kind of world we live in and what kind of beings we are.

When an anomaly appears—when something doesn’t fit the categories—it threatens the entire system. Mircea Eliade’s work on sacred and profane space illuminates this same principle: boundaries create meaning, and their violation creates chaos.

This is why pollution provokes such visceral reactions. The disgust we feel at hair in soup isn’t proportionate to any actual threat—it’s the body’s response to a category violation, a breach in the symbolic order.

Douglas studied extensively how different cultures handle anomalies. She found several common responses:

Reducing the anomaly by force (forcing it to fit a category)

Physically controlling it (quarantine, removal)

Avoiding it (taboo)

Labeling it as dangerous

Using it in ritual (anomalies often become sacred precisely because they’re dangerous)

Each response is an attempt to restore order—to put matter back “in place” or to reinforce the boundaries that the anomaly threatened.

Trauma as Ontological Pollution

The Survivor as “Matter Out of Place”

Now we can understand why trauma survivors feel “dirty” even when no physical contamination occurred. Trauma makes the individual feel like matter out of place—an anomaly that doesn’t fit into the ordered world of family or society.

Consider the various forms this takes:

Sexual abuse: The child’s body is touched in ways that violate the boundary between “child” and “sexual being.” The victim becomes an anomaly—they don’t fit the category of “pure child” but aren’t supposed to fit the category of “sexual adult” either. They become matter out of place in the classificatory system of the family.

Emotional abuse: The child is told they are worthless, a burden, unwanted. They become an anomaly in the family system—matter that doesn’t belong. The inner child carries this sense of being fundamentally “out of place.”

Moral injury: The soldier witnesses or participates in events that violate their moral categories. They become someone who has crossed lines that shouldn’t be crossed. They no longer fit their previous self-concept—they’re an anomaly to themselves.

Betrayal trauma: When a trusted figure violates trust, the victim’s entire classificatory system is disrupted. The category “safe person” has been contaminated. The victim may feel that they are somehow responsible for this pollution—that something about them invited the violation.

In each case, the survivor experiences themselves as anomalous—as not fitting the categories that give life meaning. They feel polluted not because germs have entered their body but because they have become, symbolically, matter out of place.

The Contagion of Shame

Douglas’s analysis of pollution illuminates another crucial aspect of trauma shame: its sense of contagion.

Pollution, in Douglas’s framework, is contagious. Things that touch polluted things become polluted themselves. This is why purification rituals are necessary—pollution spreads unless contained.

Trauma survivors often experience shame this way. They feel that their “dirtiness” spreads to whatever they touch:

“I don’t want to contaminate my children with my issues.”

“I feel like I ruin every relationship I’m in.”

“I shouldn’t be around normal people—I’ll infect them with my brokenness.”

This isn’t irrational. From an anthropological perspective, it’s perfectly coherent. If the survivor has become an anomaly—matter out of place—then contact with them threatens the order of others. The survivor is protecting the community from pollution by withdrawing, just as traditional societies quarantine the unclean.

The tragedy is that this protective withdrawal perpetuates isolation, prevents healing connection, and reinforces the sense of being fundamentally different from “clean” people.

OCD as World-Building

The Missing Link in Our Understanding

Mary Douglas’s theory provides the missing link for understanding Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder—not just as “anxiety” but as world-building.

Consider the classic OCD presentations: washing, checking, ordering, counting. Cognitive-behavioral approaches typically frame these as anxiety reduction strategies—the ritual temporarily lowers anxiety, which reinforces the behavior. But this misses the deeper structure of what’s happening.

The person with contamination OCD isn’t primarily trying to reduce anxiety. They’re trying to restore a symbolic order that has been disrupted. The ritual is an attempt to put matter back “in place”—to re-establish the boundaries of the world, to separate the clean from the unclean, the safe from the dangerous.

This is why simple anxiety reduction doesn’t work. You can’t solve a classification crisis by relaxation techniques. The problem isn’t that the person is too anxious—it’s that their symbolic world has lost coherence. The ritual is a desperate attempt to rebuild it.

The Trauma-OCD Connection

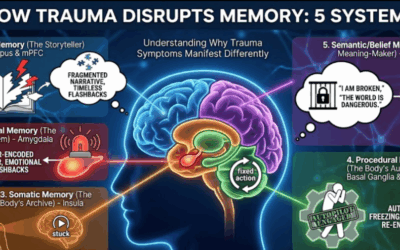

Research increasingly confirms what clinicians have long observed: OCD often emerges or intensifies following trauma. The standard explanation is that trauma elevates baseline anxiety, making obsessions and compulsions more likely. Douglas’s theory offers a deeper explanation.

Trauma disrupts classificatory systems. It creates anomalies—matter out of place—that threaten the coherence of the survivor’s world. OCD rituals are attempts to restore order to this disrupted world.

The person who washes compulsively after sexual assault isn’t primarily trying to remove germs. They’re trying to re-establish the boundary between their body and the violation. They’re trying to put their body back “in place” as clean, as their own, as distinct from what happened to it.

The person who checks locks repeatedly after a break-in isn’t primarily worried about future burglars. They’re trying to re-establish the boundary between inside and outside, safe and unsafe. They’re rebuilding a world where categories hold.

The person who orders objects meticulously after losing a parent isn’t primarily reducing anxiety. They’re creating order in a world where the fundamental category—”parent will always be there”—has been violated. If they can keep their environment in place, perhaps they can keep the world coherent.

Clinical Implications

This understanding transforms our approach to OCD treatment:

Honor the attempt: The client isn’t being “irrational.” They’re attempting to solve a real problem—the disruption of their symbolic world. The ritual has deep meaning, even if it doesn’t achieve its goal.

Address the underlying disorder: If OCD is about restoring classificatory order, then treatment must help the client find other ways to establish meaning and coherence. This might involve processing the trauma that disrupted their categories in the first place.

Work with ritual, not just against it: Rather than simply extinguishing rituals through exposure, help the client find more effective rituals—symbolic acts that actually restore their sense of order. (More on this below.)

Recognize the wisdom: The client’s intuition that something is wrong with the world isn’t mistaken. Trauma did violate their categories. The problem isn’t the perception of disorder—it’s the ineffective method of restoration.

De-Pathologizing “Feeling Ruined”

A Structural Problem, Not a Moral Failing

Perhaps the most important clinical application of Douglas’s theory is this: it de-pathologizes the sensation of feeling “ruined.”

When a trauma survivor says “I feel dirty,” “I feel damaged,” “I feel ruined,” the typical therapeutic response is some version of: “Those are just feelings. They’re not reality. You’re not really dirty/damaged/ruined.” This is meant to be reassuring, but it often falls flat. The client knows, intellectually, that they’re not covered in germs. The knowing doesn’t help.

Douglas’s framework offers a different response: “Of course you feel polluted. Your symbolic world was violated. You’ve become, in the logic of that world, matter out of place. The feeling is accurate to your structural situation—it’s not a delusion or a distortion.”

This validation often produces immediate relief. The client isn’t crazy. They’re not “too sensitive” or “stuck.” They’re responding coherently to a real violation of symbolic order.

But—and this is crucial—the feeling being “accurate” doesn’t mean the client is actually ruined. It means that their classificatory system has been disrupted. The solution isn’t to deny the feeling but to restore the order—to perform the symbolic work of purification and reintegration.

This is the difference between a moral failing and a structural problem. A moral failing implies that something is wrong with the person. A structural problem implies that something happened to the person’s world, and it can be repaired.

The Crisis of Classification

Shame, in this framework, is fundamentally a crisis of classification. The person doesn’t know where they fit. They’ve become an anomaly—and anomalies, as Douglas showed, are dangerous and threatening.

Traditional shame work often focuses on challenging the “shame voices” or developing self-compassion. These are valuable, but they may not reach the structural level. The client can develop self-compassion for being an anomaly while still experiencing themselves as an anomaly. The category crisis remains.

True resolution requires reclassification—finding a way for the person to once again fit coherently in the symbolic order. This might mean:

Expanding categories to include the anomaly (e.g., “survivors” becomes a recognized, valued category)

Creating new categories (e.g., “I’m someone who has been through something terrible and emerged changed”)

Recognizing that the original classification system was flawed (e.g., “The system that said abuse victims are ‘ruined’ was itself corrupt”)

Performing rituals of purification and reintegration

This last option—ritual—is where anthropology most directly enters the therapy room.

Ritual as Purification and Restoration

The Universal Human Response

Every known human culture has developed rituals of purification. Baptism, mikveh, sweat lodge, ablution, confession—across religions and traditions, humans have intuited that symbolic pollution requires symbolic cleansing.

This isn’t magical thinking. It’s psychological wisdom encoded in cultural practice. Mircea Eliade’s research on ritual demonstrated that these practices serve essential psychological functions: they restore the individual to their proper place in the cosmic and social order.

Modern secular therapy, in its understandable rejection of religious frameworks, often threw out this wisdom. We treat trauma with cognitive techniques and medication, but we don’t offer rituals of purification. This may be one reason why trauma therapy often “works” cognitively but fails to reach the deeper sense of contamination.

The survivor can believe, intellectually, that they’re not ruined—while still feeling polluted. What’s missing is the ritual that would restore them to their proper place in the symbolic order.

Therapeutic Rituals

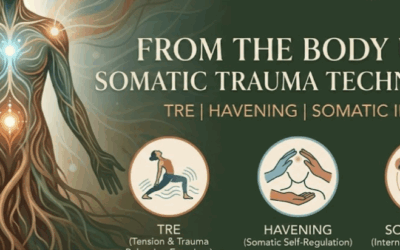

Many effective trauma therapies already incorporate ritual elements, even if they don’t use that language:

Burning letters: Writing to an abuser and then burning the letter is a classic therapeutic ritual. In Douglas’s framework, we can understand why it works. The letter externalizes the contaminating material—gets it “out of” the self and “onto” paper. The burning destroys it utterly, eliminating the anomaly from the world. Fire, cross-culturally, is a purifying element.

Somatic shaking: Peter Levine’s work on completing the trauma response involves allowing the body to shake, tremble, and discharge the freeze energy. In anthropological terms, this is a purification ritual—the body expelling the foreign element, literally shaking off the contamination. The body-brain knows how to restore itself to order if given the opportunity.

EMDR and Brainspotting: The bilateral stimulation in EMDR and the focused gazing in Brainspotting might be understood as rituals of integration—symbolic acts that help the brain process and “place” traumatic material that had been experienced as anomalous.

Testimony and witnessing: When the survivor tells their story to a therapist who fully receives it, this functions as a ritual of reintegration. The story, which had been an anomaly (unspeakable, outside the normal order of discourse), is now spoken and witnessed. The survivor moves from being isolated with their pollution to being received by the community. The witness, by not becoming contaminated, demonstrates that the survivor isn’t actually contagious.

Naming ceremonies: Some therapists work with clients to create new names or identities that reflect their post-trauma self. This is explicit reclassification—the creation of a new category that the person can coherently occupy.

Designing Effective Rituals

Based on Douglas’s theory and traditional purification practices, effective therapeutic rituals tend to share certain features:

Externalization: The contaminating material must be symbolically moved from “inside” to “outside.” This might involve writing, drawing, speaking aloud, or physical movement.

Destruction or transformation: The externalized material must be dealt with—burned, buried, washed away, transformed into something else. Simply externalizing isn’t enough; the anomaly must be resolved.

Boundary restoration: The ritual should clearly re-establish the boundaries that were violated. This might involve physical actions (washing, anointing, marking the body) or spatial actions (crossing a threshold, entering a new space).

Witness: Purification rituals typically require a witness—someone who represents the community and confirms the person’s restoration to clean status. In therapy, the therapist serves this function. The therapist’s presence transforms private suffering into witnessed transformation.

Marking: The transition should be marked in some way—a physical object, a word, a gesture that the person can return to. This marking confirms that something has changed, that they are now “on the other side” of the purification.

Clinical Applications

Assessment Through the Lens of Order

Douglas’s framework suggests new questions for clinical assessment:

“Where do you feel you don’t fit?” (Identifying the experience of anomaly)

“What categories have been violated?” (Understanding the classificatory crisis)

“What would it mean to be ‘clean’ again?” (Understanding the client’s implicit theory of purification)

“What rituals have you tried?” (Understanding existing attempts at restoration—including OCD rituals)

These questions help the therapist understand the structure of the client’s shame, not just its content.

Reframing for Clients

The Douglas framework can be shared with clients in accessible language:

“What you’re describing—feeling ‘dirty’ or ‘ruined’—makes complete sense from an anthropological perspective. Every human culture recognizes that certain experiences can make people feel polluted, even when nothing physical has happened. This isn’t because something is wrong with you—it’s because your sense of where you fit in the world has been disrupted. Your classification system has been violated.

The good news is that humans have also developed ways of restoring this order—rituals of purification that help people move from ‘contaminated’ back to ‘clean.’ These aren’t magical; they’re symbolic actions that help your mind and body re-establish the boundaries that were violated. Part of our work together might involve finding or creating rituals that help you feel restored to your proper place.”

This reframe accomplishes several things:

Normalizes the experience across human cultures

De-pathologizes the feeling of contamination

Offers a pathway forward (ritual restoration)

Positions the client as active agent in their healing

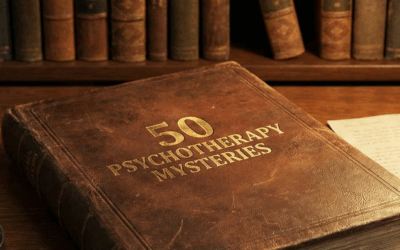

Case Example: Maria

Maria was 34 when she came to therapy reporting severe OCD symptoms that had emerged three years earlier, shortly after her mother’s death. She spent hours each day organizing her closet, arranging items in precise patterns, and feeling overwhelming anxiety when anything was out of place. Standard OCD treatment had provided limited relief.

Through exploration, it emerged that Maria’s mother had been highly critical and unpredictable throughout Maria’s childhood. Maria had coped by trying to be “perfect”—maintaining order in her room, her appearance, her behavior—as a way of avoiding her mother’s attacks. Her mother’s death had disrupted this system entirely. The person Maria had organized her life around was gone. She no longer knew where she fit.

The OCD symptoms, understood through Douglas’s lens, were attempts to restore symbolic order to a world that had lost its organizing principle. The closet organization was a microcosm—a domain where Maria could still establish and maintain categories, even as the larger categories of her life (daughter, target-of-criticism, performer-of-perfection) had collapsed.

Therapy involved several elements:

Grieving the loss of her mother and the loss of her classificatory system

Developing new categories for understanding herself (not just as “daughter of a critical mother” but as a person with her own identity)

Creating a ritual for “laying to rest” her old organizing system—including literally organizing and then deliberately disarranging her closet as an act of liberation

Finding new sources of order that weren’t based on anxiety and performance

The OCD symptoms decreased significantly, but more importantly, Maria reported feeling less “lost” in the world—more able to answer the question of where she belonged.

The Wisdom of Disgust

Listening to the Body’s Knowledge

One final implication of Douglas’s work: the body’s disgust response carries wisdom that shouldn’t be quickly overridden.

When a trauma survivor feels contaminated, their body is telling them something true: a violation has occurred. The boundaries of self have been breached. Something that should have stayed outside has gotten inside, or vice versa.

Therapy shouldn’t aim to simply eliminate this disgust response. Instead, it should help the client complete what the disgust is trying to accomplish: the restoration of proper boundaries, the expulsion of foreign elements, the return to an ordered world.

Somatic approaches to trauma often work precisely because they allow the body to complete its protective responses. The body knows things that the conscious mind doesn’t. The feeling of contamination is one such knowledge—and it requires a somatic, ritual response as much as a cognitive one.

Beyond Individual Therapy

Douglas’s framework also suggests that healing from shame may require more than individual therapy. If pollution is fundamentally about classification within a social order, then restoration may require community involvement.

This is why group therapy can be so powerful for shame work. In the group, the person who feels like an anomaly discovers that others share their experience—that there’s actually a category for people like them. The “matter out of place” finds a place.

It’s also why family therapy, when possible and safe, can be important. If the family system was where the original classification violation occurred (the child was treated as matter out of place), then restoration may require either transformation of that system or explicit separation from it—a ritual of departure that establishes new boundaries.

Restoring the Symbolic Order of the Self

Mary Douglas never intended her anthropological theories to be applied to clinical psychology. Yet her insights about pollution, taboo, and symbolic order speak directly to some of the most intractable problems in trauma therapy.

The survivor who feels “dirty” isn’t delusional—they’re accurately perceiving their symbolic displacement. The person with contamination OCD isn’t simply anxious—they’re desperately trying to rebuild a coherent world. The client who insists they’re “ruined” isn’t being dramatic—they’re reporting a crisis of classification that threatens their entire sense of meaning.

Understanding trauma as ontological pollution opens new therapeutic possibilities. We can honor the wisdom of disgust rather than dismissing it. We can design rituals that actually restore symbolic order rather than simply managing symptoms. We can help clients find or create categories where they can once again fit—where they’re no longer anomalies but recognized members of the human community.

Shame is not a moral failing. It’s a structural crisis. And structural crises require structural solutions—the symbolic work of purification, boundary restoration, and reintegration that humans have performed for as long as we’ve been human.

The therapy room can become a space of ritual purification—a liminal zone where the old classifications are dissolved and new ones are created, where the polluted are washed clean and restored to their proper place. This is ancient work, dressed in modern clothing. And it remains as necessary now as it was when Mary Douglas first revealed the hidden logic of purity and danger.

References and Further Reading

Primary Anthropological Sources:

Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. Routledge, 1966.

Douglas, Mary. Natural Symbols: Explorations in Cosmology. Pantheon, 1970.

Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane. Harcourt, 1957.

Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Aldine, 1969.

Clinical and Research Resources:

National Institute of Mental Health: OCD

American Psychological Association: PTSD Clinical Practice Guideline

PubMed: Moral Injury and Trauma

NCBI: Disgust and Contamination Fear in OCD

Somatic and Ritual Approaches:

Levine, Peter. Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. North Atlantic Books, 1997.

van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score. Viking, 2014.

0 Comments