The Mystical Depths of the Psyche: Exploring the Intersection of Mysticism, Psychology, and Psychotherapy

The Inward Journey

In the medieval period, pilgrims embarked on perilous journeys to the Holy Land, facing unknown dangers and cultural dissonance far from home. These pilgrimages were more than mere travel; they were opportunities for profound self-discovery and spiritual growth. As pilgrims prayed, fasted, and sought inner peace, they metaphorically retraced Jesus’s life journey, much like the stations of the cross.

For those unable to undertake such arduous voyages, an alternative emerged: the labyrinth. Often found adorning cathedral floors, these intricate stone patterns lit by flickering candles offered a symbolic pilgrimage. At first glance, the labyrinth appears as a confounding maze, its path twisting and turning unpredictably. Yet, upon closer inspection, it reveals itself as a single, unambiguous route inevitably leading to the center.

This labyrinth serves as a powerful metaphor for the mystical practices we explore in this article. As we traverse its path, we relinquish the need for rational decision-making, allowing our conscious mind to quiet. The repetitive action of walking, free from the demands of executive function, facilitates a winding down of the ego. In this state, we access a different level of consciousness, tuning into the deeper recesses of our mind, heart, and perhaps soul.

The labyrinth, like the mystical practices we will discuss, is not about physical movement through the world, but an inward journey of self-discovery. It is a tool for concentration, helping us focus on aspects of ourselves that lie beneath the ego-driven conscious mind. This inward journey forms the core of both mystical traditions and certain psychotherapeutic approaches, offering a path to profound self-understanding and healing.

Defining Mysticism: Beyond the Misunderstood

Mysticism, often misinterpreted as abstract or obscure thinking, is in fact a rich philosophical tradition with profound implications for self-understanding and spiritual growth. At its core, mysticism posits that the search for knowledge of divinity or ultimate truth requires a deep dive into self-knowledge.

This concept might initially seem threatening to some religious perspectives, as it appears to equate self-knowledge with knowledge of the divine. However, most mystics do not claim that the self is God. Rather, they propose that our capacity to understand ultimate reality is inherently limited by our understanding of ourselves. Through this lens, our traumas, fears, and undeveloped aspects of self become barriers to comprehending deeper truths. The mystical journey, then, is one of healing and self-acceptance, allowing us to perceive the world more clearly and identify our higher purpose.

In the mystical tradition, the ego – our rigid self-image and conscious, language-based thinking – is seen as an obstacle. The goal is not to identify with the ego but to access the larger unconscious mind beyond it. By dissolving the conscious mind and letting go of language-based cognition, mystics aim to contact a more authentic self, one unburdened by accumulated traumas, anxieties, and negative coping mechanisms.

This process of ego dissolution allows for a shift in temporal focus. Instead of being mired in regrets about the past or fears about the future, the individual can fully experience the present moment. Moreover, mystical techniques work to dissolve protective mechanisms like addiction, anger, avoidance, and stagnation that often shield the ego from change.

Mysticism Across Traditions: A Universal Quest

While organized religion often conjures images of hierarchies and rigid doctrines, mystical traditions exist within every major world religion. These traditions share a common goal: ego dissolution as a means of achieving oneness with the divine.

Christianity boasts a rich mystical tradition, with figures like Meister Eckhart, Simone Weil, and Julian of Norwich. In Islam, the poetry of Rumi and the broader Sufi tradition embody mystical thought. Judaism offers mystical insights through Martin Buber’s writings and the esoteric teachings of the Kabbalah. Eastern religions like Hinduism and Taoism have mysticism deeply embedded in their core teachings.

Beyond religious contexts, mysticism finds expression in the arts. Poets and artists like Rainer Maria Rilke and Hilma af Klint have explored mystical themes in their work, demonstrating the universal appeal of these ideas.

Importantly, mysticism is not confined to religious or spiritual frameworks. Non-deistic and atheistic mystical traditions also exist. Theravada Buddhism, for instance, posits that the ego-self is a delusion and seeks its complete dissolution. Yoga practices, while often associated with Hinduism, can be approached secularly, teaching practitioners to access a “body mind” state through physical movement and somatic awareness.

Despite their diverse origins, mystical traditions often converge on common themes. The discovery of an authentic self and the cultivation of deep compassion for others are recurrent motifs. Many mystics describe the experience of ego dissolution as accompanied by profound feelings of love and connection. Paradoxically, this state often involves simultaneous sensations of separateness and unity – feeling distinct from the world yet intimately connected to all things.

The ineffable nature of these experiences poses a challenge when trying to articulate them through language. The mystical state often defies easy categorization or description, existing beyond the realm of our conscious, language-oriented mind.

Mysticism in the Therapeutic Context

At first glance, the connection between mystical practices and modern psychotherapy might not be apparent. As a therapist, I don’t lead my patients in chants, yoga sessions, or hypnosis. I don’t employ psychedelic-assisted therapy. Yet, the influence of mystical concepts on my therapeutic approach is profound and pervasive.

In fact, I’ve come to believe that what we might call a “mystical experience” often marks the crucial turning point in therapy – the moment when real change occurs. This idea isn’t new. Lectures from the 1970s often referenced a transformative state “between waking and sleep” as the locus of genuine therapeutic progress. While this concept might have seemed esoteric or vague in the past, years of clinical experience have illuminated its meaning and significance.

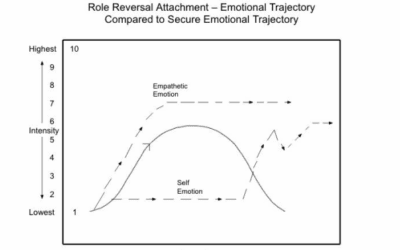

These pivotal moments in therapy often involve deep emotional releases that challenge a patient’s self-image and worldview. In essence, meaningful change occurs when the ego is temporarily suspended or “turned off.” This process involves reprogramming the subcortical brain – the part responsible for emotional reactions and body awareness – rather than merely altering conscious thoughts.

This understanding highlights a limitation of purely cognitive approaches to therapy. Cognitive techniques often attempt to strengthen the ego’s control over the psyche, essentially trying to subdue the unconscious through sheer willpower. However, the effects of this approach tend to be limited and temporary. Real, lasting change occurs not by altering our thoughts, but by transforming our deepest feelings and bodily responses.

The Mystical Dimension of Trauma Therapy

The parallels between mystical experiences and effective trauma therapy are striking and significant. Both depth psychology and somatic therapies, as well as brain-based approaches like brainspotting, prove remarkably effective in healing trauma and facilitating behavioral change. These methods share a common thread: they stimulate the subcortical brain, helping patients temporarily suspend ego functions and confront their authentic selves.

Unlike cognitive or ego-based therapies, these approaches delve into the deeper, non-verbal realms of the psyche. As a patient myself, I found brainspotting to be one of the most profoundly mystical experiences of my life, facilitating personal growth and healing beyond what I had achieved through previous therapeutic models.

Jungian Psychology: A Bridge Between Mysticism and Therapy

The intersection of mysticism and psychology finds its most explicit expression in Jungian or depth psychology. Carl Jung, the founder of this school of thought, dedicated much of his work to studying the psychological implications of mystic traditions. By looking to religion as a framework for a new psychology, Jung developed one of the most influential approaches to psychotherapy, despite facing criticism from more traditionally minded academics.

Jung’s influence extends to many modern trauma therapies. Somatic therapy, Internal Family Systems (IFS) therapy, Gestalt therapy, and even certain life coaching models all have roots in Jungian psychology. At its core, Jungian psychotherapy aims to help patients recognize and understand the various components of their unconscious mind. This process facilitates the acceptance and integration of parts of the self that have been feared, hated, or judged, bringing repressed elements into conscious awareness.

The Shadow: Jung’s Key to the Unconscious

Central to Jung’s conception of the unconscious is the idea of the shadow – those parts of ourselves that most threaten the ego and are consequently repressed. The shadow encompasses all that is “not allowed” or “not accepted” in our conscious minds. Paradoxically, it is often the shadow that gives rise to the very symptoms that bring patients to therapy.

Because the ego actively represses the shadow, it cannot control these elements when they inevitably emerge from beneath the surface of consciousness. Many aspects of ourselves resist easy acceptance and are actively repressed. Effective therapy utilizes the unconscious mind and the shadow to help us accept and integrate these uncomfortable parts of ourselves.

The shadow can contain traumatic life events and obscure their effects on us. A key aspect of Jungian psychology, and the therapeutic models it has influenced, is teaching patients to recognize their shadow and accept it as an integral part of themselves. This process is crucial for healing trauma and developing a more integrated sense of self.

Layers of Consciousness: A Therapeutic Perspective

As we delve deeper into the unconscious mind through therapy, we often encounter distinct “layers” of consciousness. While individual experiences may vary, certain common patterns emerge:

- The Avoidance Layer: This first layer contains aspects of ourselves we actively avoid acknowledging. It might include anger management issues, eating disorders, avoidance patterns, or addictions. Our ego often rationalizes these behaviors (“I deserve it” or “My job is stressful, so it’s okay”), but beneath these justifications lie emotions we’re not equipped to handle.

- The Trauma Layer: Here we find childhood or adult traumas that have dysregulated our subcortical brain. This layer contains deeply ingrained emotional assumptions that we might intellectually recognize as incorrect but default to on an emotional level. It’s where we store triggers for trauma and PTSD in our fight-or-flight system – reactions that often resist intellectual control.

- The Pre-Cognitive Layer: Many patients encounter a layer of consciousness that feels familiar yet somehow separate from their sense of self. It often manifests as strong emotions that we recognize but don’t identify with. Some patients with recorded birth trauma, for instance, describe feelings of profound abandonment and separation during therapeutic experiences like brainspotting.

- The Universal Connection Layer: At the deepest level of consciousness, many individuals report experiences that echo mystical descriptions. These often include a profound sense of empathy and connection to all things. Patients frequently describe seeing themselves “from the outside” or gaining a dramatically different perspective on their identity. Mystics have long described this state as a separation from the ego and a feeling of understanding and accepting the true self.

The Origins and Implications of Unconscious Experiences

The nature and origin of these deep unconscious experiences remain subjects of ongoing debate and inquiry. Jung referred to the deepest layer as the “collective unconscious,” suggesting that all beings share a common experiential foundation at the base of consciousness. Whether Jung attributed this to a deity or to evolutionary processes remains a point of contention among scholars.

Secular interpretations view the unconscious as a realm where we can discover our individual purpose, cultivate empathy, and achieve emotional clarity. Spiritual perspectives often frame these experiences as a union with divinity or a “godhead.”

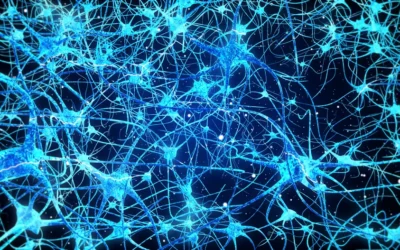

From a neurobiological standpoint, we can conceptualize consciousness as a root beginning in the ego and prefrontal cortex. As we move away from the prefrontal cortex, we lose access to language and thought-based cognition. The “root” of consciousness extends through the midbrain, engaging our movement and fight-or-flight systems, and continues into the basal ganglia, brainstem, and spinal nervous system.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Journey of Self-Discovery

The intersection of mysticism, psychology, and psychotherapy offers a rich terrain for exploration and healing. By embracing techniques that allow access to deeper levels of consciousness, individuals can confront fears, integrate repressed aspects of self, and potentially experience a profound sense of connection and understanding.

Whether interpreted through a spiritual or neuroscientific lens, these experiences provide powerful tools for personal transformation. As we continue to explore the depths of human consciousness, the ancient wisdom of mystical traditions converges with insights from modern psychology, offering new pathways for healing and self-discovery.

The journey inward, much like the winding path of the labyrinth, may seem daunting and confusing at first. Yet, by committing to the process and relinquishing our need for constant cognitive control, we open ourselves to profound insights and transformative experiences. In doing so, we not only heal our individual traumas and integrate disparate parts of ourselves but also potentially tap into a deeper, more universal understanding of our place in the world.

As therapists, embracing these concepts allows us to guide our patients through their own labyrinths of consciousness, helping them navigate the twists and turns of their psyche to reach a place of greater wholeness and authenticity. And as individuals on our own journeys of self-discovery, we can draw inspiration from both ancient mystical practices and modern psychological insights, recognizing that the path to self-understanding is as old as humanity itself, yet ever-evolving with new discoveries and approaches.

In the end, the goal remains the same as it was for those medieval pilgrims: to undertake a transformative journey, face our deepest fears and limitations, and emerge with a profound sense of connection – to ourselves, to others, and to the world around us. This journey, whether framed in mystical or psychological terms, offers the potential for healing, growth, and a more authentic way of being in the world.

0 Comments