How the Most Therapy-Literate Generation in History is Exposing the Failure of the Biomedical Model and Demanding a Return to Meaning

By Joel Blackstock, LICSW-S, Clinical Director, Taproot Therapy Collective

Something unprecedented is happening in the consulting room. A generation raised on TikTok diagnostics and Instagram infographics arrives at therapy already fluent in clinical terminology, armed with self-diagnoses derived from sixty-second videos, speaking a hybrid language of neuroscience and internet slang that their therapists often struggle to decode. They ask about “nervous system regulation” and “dorsal vagal shutdown.” They describe their experience as “functional freeze” or announce they are “in their Winter Arc.” They want to know if their sudden repulsion toward a romantic partner constitutes “the ick” of genuine incompatibility or the avoidant attachment pattern they learned about from a podcast.

This is Generation Z entering the therapeutic space, and they are not merely seeking treatment. They are, whether consciously or not, staging a quiet revolution against the very foundations of how Western psychology has conceptualized mental distress for the past century.

The data confirms the scale of this shift. According to the Harmony Healthcare IT State of Gen Z Mental Health report, 42% of Gen Z now attends therapy, representing a 22% increase since 2022. A staggering 61% have been medically diagnosed with anxiety, and 46% with depression, rates nearly double those observed in Americans over the age of 25. An additional 77% engage in self-help practices including podcasts, journaling, and digital wellness tools. This generation has normalized psychological care to a degree that would have been unimaginable even two decades ago; 87% report feeling comfortable discussing mental health, and over 60% feel comfortable sharing their struggles openly.

Yet here is the paradox that should trouble every clinician, researcher, and policy maker: despite being the most therapy-literate generation in history, Gen Z remains the most distressed. The Annie E. Casey Foundation reports that approximately 75% of mental illnesses emerge between ages 10 and 24, the very window this generation currently occupies. They know the vocabulary. They have access to unprecedented resources. They seek help at rates their grandparents would have considered shameful. And still, rates of anxiety, depression, self-harm, and suicidal ideation continue to climb.

This essay proposes that the paradox is not paradoxical at all. The problem is not that Gen Z seeks too much therapy or too little. The problem is that the dominant model of psychological treatment, the biomedical paradigm that has governed American mental healthcare for over three decades, is fundamentally inadequate to the kind of suffering this generation experiences. Gen Z knows this intuitively, which is why their pop psychology vocabulary, for all its imprecision and potential for misuse, represents something more significant than mere trend: it represents a groping toward a different way of understanding the mind, one that integrates body and narrative, neuroscience and mythology, mechanism and meaning.

What this generation seeks, and what the field must learn to provide, is not merely diagnosis and symptom reduction. It is a psychology that tells them a story about who they are and why they suffer and how transformation becomes possible. It is, in a phrase I have come to use in my own practice, a bio-mythology of the psyche.

The Epidemiological Context and the Treatment-Prevalence Paradox

To understand what Gen Z is rejecting, we must first confront the sheer scale of the crisis they inhabit and the strange paradox at its heart. By 2025, the narrative has shifted from “raising awareness” to managing a deluge of acuity that threatens to overwhelm existing infrastructure. For Gen Z, anxiety is not an intermittent state but a chronic baseline, fundamentally altering their relationship with the healthcare system.

The statistical baseline reveals a generation where pathology has effectively normalized. According to the Thriving Center of Psychology 2025 report, 93% of Gen Z and Millennials hope to improve their mental health, with 39% planning to start therapy within the next year. Among those currently in therapy, 89% say it is worth the cost, though one in three must make financial sacrifices, cutting back on travel, dining, and social experiences to afford their sessions. The intent to seek care is nearly ubiquitous, but the means remain restricted.

This diagnostic saturation suggests a fundamental shift in the threshold for clinical labeling. Whereas previous generations might have categorized periods of intense worry or low mood as “temperament” or “situational stress,” Gen Z, armed with diagnostic vocabulary acquired through digital osmosis, is far more likely to seek and receive a formal medical label. The UNICEF Perception of Youth Mental Health Report 2025 identifies what researchers term the “News Consumption Paradox”: Gen Z consumes news more voraciously than any other content type, driven by a desire to have agency in shaping the future, viewing being informed as a moral imperative. Yet this engagement is the primary engine of their distress. Approximately 60% report feeling overwhelmed by events in their community, country, and the world.

This creates a therapeutic bind that challenges traditional models. To disconnect is to feel guilty and uninformed, stripping them of agency, but to stay connected is to be chronically flooded with stress hormones. For a Gen Z client watching real-time coverage of geopolitical conflict or climate degradation, the “catastrophe” is not a cognitive distortion to be corrected; it is an objective reality to be endured. Therapists treating this generation report that validating “eco-anxiety” and “political stress” as rational responses is a prerequisite for therapeutic alliance. The clinical goal shifts from “fixing the thought” to “building capacity to endure the reality.”

Yet despite this massive engagement with mental health concepts and services, outcomes have not improved. This is the treatment-prevalence paradox: more therapy has not produced less suffering. And this paradox points toward a fundamental inadequacy in the model being offered.

The Machine Model vs. The Depth Model

| Feature | The Machine Model (CBT/ABA) | The Depth Model (Post-Secular/Process) |

| Metaphor | Computer / Robot | Dreambody / Ecosystem in Flux |

| Goal | Functionality / Compliance | Individuation / Meaning |

| Symptom View | Error / Dysfunction / Bug | Signal / Ally / Dream |

| Mechanism | Extinction / Conditioning | Reconsolidation / Unfolding |

| Concept of Self | “No Self” / Reflex Arc | Ego-Self Axis / Archetypal Soul |

| Cultural Driver | Neoliberal Efficiency | Post-Secular Sacred |

The Biomedical Model and Its Discontents

The biomedical model of mental illness, as articulated in a landmark Clinical Psychology Review analysis, posits that mental disorders are brain diseases caused by neurotransmitter dysregulation, genetic anomalies, and defects in brain structure and function. Treatment, in this framework, consists primarily of pharmacological interventions designed to correct presumed biological abnormalities. The brain is conceived as a machine that has malfunctioned; the psychiatrist or clinician serves as a technician who repairs the malfunction.

This model has dominated American psychiatry and, by extension, American psychology for more than three decades. During this period, psychiatric medication use has sharply increased, and mental disorders have become commonly regarded as brain diseases caused by chemical imbalances that are corrected with disease-specific drugs. Public education campaigns, patient advocacy groups, and pharmaceutical marketing have successfully convinced the American public that anxiety is a serotonin deficiency, that depression results from insufficient dopamine, that the proper response to psychological distress is chemical intervention.

The appeal of this model is obvious. It destigmatizes mental illness by framing it as no different from diabetes or hypertension, a medical condition rather than a moral failing. It provides a clear treatment pathway: identify the disorder, prescribe the medication, monitor the response. It offers the comfort of scientific authority in a domain historically plagued by theoretical fragmentation.

The Biomedical Model vs. The Common Factors Model

| Feature | Biomedical Model | Common Factors Model |

| Primary Mechanism | Specific Ingredients (Drugs, Protocols) | Therapeutic Alliance, Empathy, Goal Consensus |

| View of Patient | Carrier of biological dysfunction | Active agent with innate resources |

| Role of Therapist | Technician delivering intervention | Partner in meaning-making |

| Economic Fit | High (Quantifiable, Scalable) | Low (Hard to quantify/industrialize) |

| Philosophical Root | Logical Positivism / Modernism | Humanism / Phenomenology / Metamodernism |

| Response to “Placebo” | “Noise” to be eliminated | “Meaning Response” to be harnessed |

Yet as the ScienceDirect analysis documents, despite widespread faith in the potential of neuroscience to revolutionize mental health practice, the biomedical model era has been characterized by a broad lack of clinical innovation and poor mental health outcomes. Scientists have not identified a biological cause of, or even a reliable biomarker for, any mental disorder. The chemical imbalance theory, so persuasive in pharmaceutical advertising, lacks credible scientific support. As psychiatrist George Engel noted in his critique published in Science, a biomedical model based on the exclusive treatment of physical constituent parts cannot provide the correct concept of human suffering and healing, and consequently cannot guarantee effective healthcare.

The Springer analysis of complexity and reductionism in the biomedical model identifies a deeper problem: the model sees a person the way one might see a car engine, as a whole best understood by studying and treating its individual parts in separation. In some extreme cases, healthy human responses to inhumane life conditions, such as severe childhood trauma or chronic oppression, are defined as psychiatric disorders and approached primarily from a biological perspective. Once a problem is characterized as a biomedical problem, one naturally starts to search for a biomedical solution, even when the problem is fundamentally social, relational, or existential.

Gen Z has absorbed this critique, often without being able to articulate it formally. They have watched their peers medicated from childhood. They have experienced the revolving door of psychiatric care: the fifteen-minute medication check, the trial-and-error approach to finding the right pill, the side effects that sometimes seem worse than the original symptoms. According to the Harmony Healthcare IT data, 34% of Gen Z currently take prescription medication for mental health, while an additional 19% report turning to non-prescribed substances like cannabis to manage symptoms. They have learned, through bitter experience, that the promise of the biomedical model remains largely unfulfilled.

This is why they arrive at therapy speaking a different language, one the biomedical model never taught them. When a Gen Z client describes herself as being in “dorsal vagal shutdown,” she is not merely using trendy terminology. She is reaching for a framework that acknowledges the body as a participant in psychological experience rather than merely a vessel for brain chemistry. When a young man explains that he “crashed out” after suppressing his anger for months, he is groping toward an understanding of the psyche as a dynamic system that can be overwhelmed, not merely a collection of neurotransmitters that need rebalancing.

The New Lexicon of Dysregulation

To work effectively with this generation, clinicians must learn to decode their language. What follows is not merely a glossary but an attempt to bridge the gap between pop psychology terminology and clinical understanding, to extract the valid intuitions embedded in internet slang and connect them to the deeper frameworks they are reaching toward. For each term, I will provide the clinical meaning, the archetypal dimension, and the therapeutic implications.

Based on the research regarding Generation Z’s linguistic habits and the “therapy speak” phenomenon, here is a chart contrasting Gen Z’s conceptualization of mental health terms with the traditional biomedical or clinical expectations.

The Semantic Gap: Gen Z “Therapy Speak” vs. Clinical Reality

| Gen Z Term / Slang | Gen Z Conceptualization & Expectation | Biomedical / Clinical Model Definition |

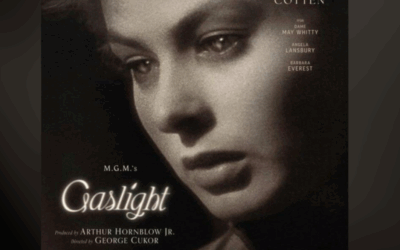

| “Gaslighting“ |

Usage: Any instance of lying, disagreement, or invalidating one’s perspective in a conflict. Expectation: Absolute validation of one’s internal reality; any challenge to that reality is viewed as abusive. |

Definition: A specific form of psychological abuse involving a sustained, systematic dismantling of a victim’s sanity and grasp on reality over time. Disagreement is not gaslighting. |

| “Boundaries“ |

Usage: Ultimatums or rules imposed on others to control their behavior (e.g., “My boundary is you can’t talk to her”). Expectation: Others must comply with these demands to maintain access to the relationship. |

Definition: Limits set on one’s own behavior and exposure to protect well-being (e.g., “I will leave the room if you yell”). They are self-protective, not controlling of others. |

| “Trauma” / “Traumatized“ |

Usage: Applied to distressing or uncomfortable life events (e.g., a breakup, a mean boss, an embarrassing moment). Expectation: These events should be treated with the gravity of a deep psychological wound; requires “trigger warnings.” |

Definition: Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence (DSM-5 criteria). While “small t” trauma exists, clinical models distinguish it from acute PTSD-inducing events. |

| “Narcissist“ |

Usage: Anyone who is selfish, breaks up with you, or is “toxic.” Expectation: The person is fundamentally flawed/evil and should be “cut off” immediately; no empathy required. |

Definition: A person with Narcissistic Personality Disorder (NPD), a pervasive, complex personality disorder characterized by grandiosity and lack of empathy, often masking deep insecurity. |

| “OCD” (Obsessive) |

Usage: Being organized, liking neatness, or having specific preferences. Expectation: A quirk or personality trait (“I’m so OCD about my notes”). |

Definition: A debilitating disorder involving intrusive, unwanted thoughts (obsessions) and ritualistic behaviors (compulsions) performed to relieve intense anxiety, often impeding function. |

| “Menty B” |

Usage: A “Mental Breakdown.” A casual, often humorous term for a period of high stress, crying, or burnout. Expectation: Acknowledgment of struggle and a need for a break/self-care without necessarily implying severe pathology. |

Definition: “Nervous breakdown” is not a clinical term. Clinically, this refers to an acute phase of a disorder (e.g., psychosis, severe depressive episode) rendering the patient unable to function. |

| “Nervous System Regulation” |

Usage: A lifestyle aesthetic (e.g., finding “glimmers,” “rotting” in bed) to avoid all stress. Expectation: Immediate relief from discomfort; equating all stress/activation with harm. |

Definition: The physiological process of moving between states of arousal and calm. The goal is flexibility and resilience (capacity to handle stress), not a permanent state of calm. |

| “Vibe Check” |

Usage: An intuitive assessment of safety, authenticity, and alignment. Expectation: Immediate emotional resonance. If the “vibe is off,” the person/therapist is unsafe or incompatible. |

Definition: Clinical Intake / Assessment. A structured evaluation of history, symptoms, and goals to determine clinical fit and treatment plan, which may take multiple sessions. |

| “Gen Z Stare” |

Usage: A defense mechanism of going blank/still during face-to-face conflict. Expectation: “Preservation” of the nervous system; refusing to perform emotions for the other person. |

Definition: Dissociation or Shutdown. A disconnection from thoughts, feelings, or sense of self, often a symptom of trauma or severe anxiety; distinct from healthy boundary setting. |

| “Self-Diagnosis” |

Usage: Identifying with a condition (ADHD, Autism) based on relatable content (e.g., TikTok algorithms). Expectation: Clinicians should affirm this identity (“green flag”) rather than question it (“red flag”). |

Definition: Diagnosis requires rigorous assessment against standardized criteria (DSM-5/ICD-11) to rule out differentials. Relatability is not diagnostic evidence. |

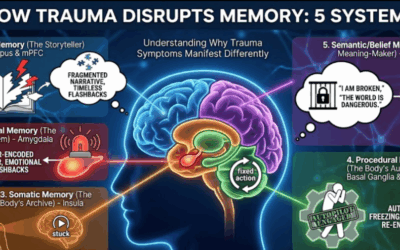

Somatic Health: The Body Speaks

Functional Freeze and High-Functioning Freeze

When Gen Z describes “functional freeze,” they are naming an experience that traditional diagnostic categories capture poorly. Unlike major depression, which connotes sadness and lethargy, functional freeze describes a paradoxical state: externally productive, even high-achieving, while internally experiencing profound disconnection, numbness, and paralysis. The individual goes to work, meets deadlines, maintains a social calendar, yet feels as though watching their own life from behind glass.

Clinically, this maps to the dorsal vagal state described in Polyvagal Theory. When neither fight nor flight is possible, when the nervous system determines that no mobilization strategy will succeed, it defaults to the ancient reptilian strategy of metabolic conservation and shutdown. Heart rate drops. Blood pressure falls. Dissociation occurs. Yet in the modern world, this shutdown does not manifest as the obvious immobility of a possum playing dead; it manifests as going through the motions while internally absent.

The term captures a truth that the biomedical model struggles to accommodate: that the most ancient survival strategies of the nervous system can persist beneath a veneer of competence, that one can be simultaneously functional and frozen. The users searching for this term are high achievers who do not identify with traditional depression symptoms but recognize that their internal experience is one of paralysis. They are searching for validation that their exhaustion is not “laziness” but a biological survival response.

The archetypal dimension becomes clear when we consider the “Frozen Child” underlying this state. This is not merely a physiological response but a psychological posture, the part of the self that learned early that visibility meant danger, that the safest strategy was to become invisible while still performing the motions of life. Willpower cannot break a biological freeze because the freeze exists precisely because willpower was once insufficient to ensure safety. The body learned to bypass the will entirely, and the body must be involved in any genuine thaw.

Treatment implications point toward somatic modalities. Brainspotting, developed by Dr. David Grand, uses eye positions to access subcortical brain regions where this freeze is stored, allowing processing to occur beneath the level of verbal narrative. The goal is not insight alone but physiological release, helping the body complete the defensive responses that were interrupted when freeze became the only option.

Cortisol Face and Moon Face Stress

The “cortisol face” phenomenon, in which individuals attribute facial puffiness and bloating to chronic stress, has been widely dismissed by dermatologists as pseudoscience. Medically, “moon face” results from Cushing’s syndrome or prolonged steroid use, not from ordinary stress. The Ohio State University Health analysis confirms that cortisol face as popularly understood is not a clinical entity.

Yet the dismissal misses the point entirely. The users searching for this term are expressing a valid intuition: that chronic stress manifests physically, that the body cannot be separated from the mind, that what Bessel van der Kolk calls “the body keeping the score” includes visible, somatic markers of psychological distress. Chronic sympathetic activation does produce inflammation, cortisol dysregulation, and changes in physical appearance. The specific mechanism may differ from what TikTok suggests, but the underlying insight, that the body reflects psychological reality, is sound.

From a depth psychology perspective, “cortisol face” represents the body as Shadow, the aspect of self that cannot be hidden regardless of how successfully the persona is maintained. The face reveals what words conceal. The Wounded Warrior who has been mobilized for too long eventually shows the wear, whether or not the bearer wishes to acknowledge it. The strategic clinical pivot is to validate the underlying somatic reality while correcting the specific mechanism, using the client’s concern about physical appearance as an entry point into deeper work on HPA axis dysregulation and chronic stress patterns.

Glimmers and Polyvagal Positivity

If “trigger” defined the 2010s mental health landscape, “glimmer” may define the late 2020s. Coined by clinician Deb Dana in her application of Polyvagal Theory, a glimmer is the opposite of a trigger: a micro-moment of safety, connection, or joy that activates the ventral vagal system. The warmth of sunlight on skin. The sound of a friend’s laughter. The satisfaction of a task completed. The comfort of a familiar smell.

The popularity of this term reflects a profound hunger for positive neuroplasticity, for frameworks that emphasize building capacity rather than merely processing trauma. Gen Z has grown weary of “trauma dumping” culture, the endless excavation of wounds without apparent healing. Glimmers offer a hopeful counter-narrative: the nervous system can be trained to recognize safety, not only danger.

Archetypally, the search for glimmers represents the Magician’s function of directing attention. The Magician governs perception, the capacity to see what others miss, to shift the frame and thereby transform experience. Trauma trains the Reticular Activating System to scan for threats; therapy trains it to scan for glimmers. The Magician learns to find gold where others see only dross. Meanwhile, the Lover archetype, which governs connection and joy, provides the relational context in which glimmers become possible. We cannot glimmer in isolation. The ventral vagal state requires village.

The clinical work involves teaching clients to become “glimmer hunters,” actively scanning their environment for micro-moments of safety and allowing the body to savor them rather than rushing past. This is not positive thinking or gratitude practice in the conventional sense. It is the deliberate training of neuroception to recognize safety, the recalibration of an oracle that has been predicting danger too indiscriminately for too long.

Neurodivergence: The Civil War Within

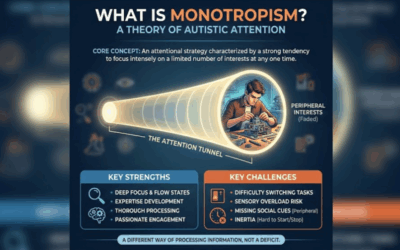

AuDHD and the Explorer-Ruler Conflict

Search volume for “AuDHD,” the co-occurrence of autism and ADHD, has exploded in recent years, reflecting both increased recognition that these conditions frequently overlap and a growing community of individuals who feel that neither diagnosis alone captures their experience. Research on neurodivergent trends confirms that the AuDHD intersection represents one of the fastest-growing areas of clinical interest.

The AuDHD individual lives in a state of internal contradiction. ADHD demands novelty, stimulation, spontaneity. Autism demands routine, predictability, sensory control. Standard ADHD advice, embrace flexibility, seek new experiences, often harms the autistic nervous system. Standard autism advice, maintain strict routines, minimize sensory input, often suffocates the ADHD need for dopaminergic stimulation. The person exists in perpetual negotiation between warring needs.

Archetypally, this represents a conflict between the Explorer or Creator, which drives the ADHD pursuit of novelty, and the Ruler or King, which demands the order and structure autism requires. When these archetypes are integrated, the result can be extraordinary: the person who creates novel systems, who imposes beautiful order on chaotic domains, who explores deeply rather than broadly. When they are at war, the result is burnout, paralysis, and the desperate question: “Which part of myself must I sacrifice today?”

qEEG brain mapping offers particular value here because it can visualize these competing neurological patterns. The ADHD signature, with its characteristic theta-beta abnormalities, appears alongside autistic patterns involving alpha and gamma irregularities. Seeing the conflict mapped physiologically often brings relief: the internal civil war is not imagined, not a failure of will, but a genuine neurological reality that requires integration rather than conquest.

The Dopamine Menu and Alchemical Self-Regulation

The “dopamine menu” is a viral productivity concept that has spread through ADHD communities with remarkable speed. Users create literal menus of activities organized by dopamine intensity, as documented in ADDitude Magazine’s analysis:

Appetizers represent quick, low-investment dopamine hits: petting a dog, drinking cold water, stepping outside for fresh air.

Mains represent deeply satisfying activities requiring more investment: creative flow states, vigorous exercise, meaningful conversation.

Sides represent dopamine added to otherwise aversive tasks: listening to podcasts while cleaning, drinking a special coffee while doing paperwork.

Desserts represent high-stimulation, low-value activities to be used sparingly: social media scrolling, video games, online shopping.

Clinically, this represents Behavioral Activation, a CBT technique, repackaged for the neurodivergent brain. The menu metaphor makes executive function deficits more manageable by reducing decision fatigue and providing structure for self-regulation.

The archetypal frame here is the Alchemist, the one who transforms base matter into gold. The Alchemist knows that transformation requires ingredients, that the Great Work cannot proceed from nothing. When Gen Z creates a dopamine menu, they are engaging in modern ritual: identifying the substances (activities) that fuel their particular transformation, organizing them according to potency, creating a system for conscious engagement with their own neurochemistry.

This connects directly to micronutrition and the understanding that you cannot “order from the menu” if the “kitchen” has no ingredients. Vitamins B6, B9, iron, and zinc serve as cofactors for dopamine synthesis. The menu is useless if the brain lacks the raw materials to produce what the activities are meant to stimulate. The Alchemist needs matter to work with.

Body Doubling and Parallel Play

“Body doubling” refers to working alongside another person to facilitate focus, while “parallel play” describes existing in shared space without direct interaction. Both terms have exploded in neurodivergent communities, validating experiences many individuals thought were personal quirks.

The clinical insight here involves co-regulation. The mammalian nervous system evolved for interdependence. Research on the neuroception of safety confirms that we regulate better in the presence of safe others because their regulated states communicate cues of safety that our neuroception reads and responds to. Body doubling works because another regulated presence helps stabilize our own autonomic state, reducing the anxiety and overwhelm that interfere with executive function.

For neurodivergent individuals whose nervous systems are more easily dysregulated, this effect is amplified. The presence of another human body, even one engaged in entirely separate activities, provides the co-regulatory scaffold that allows the individual to access capacities unavailable in isolation. This is not weakness or dependency. It is mammalian biology expressed in contemporary form.

Emotional Slang: The Shadow Speaks

Crash Out

“Crashing out” has emerged as the dominant term for sudden, explosive loss of emotional control, particularly among young men. According to Crisis Text Line’s analysis, the term describes a systemic failure, a machine pushed beyond its limits until catastrophic breakdown occurs. Unlike “tantrum,” which implies immaturity, or “anger management issues,” which implies pathology, “crashing out” frames the experience as overwhelming rather than characterological.

Clinically, this maps to acute sympathetic flooding, the “amygdala hijack” in which the thinking brain is overwhelmed by limbic activation. The person loses access to reflective capacity, to impulse control, to the executive functions that normally modulate emotional expression. They become, in their own words, “a different person.”

Bed Rotting versus Hurkle-Durkling

A fascinating linguistic distinction has emerged between “bed rotting” and “hurkle-durkling,” a resurrected Scottish term for pleasurable lounging. Both describe extended time in bed without sleeping, but the connotations differ entirely.

According to Sleepopolis analysis, bed rotting carries negative valence: passive content consumption, ignored responsibilities, the sensation of decay and dissociation. Hurkle-durkling carries positive valence: intentional rest, coziness, the Scandinavian “hygge” of comfortable withdrawal.

This distinction perfectly mirrors the difference between dorsal vagal shutdown and ventral vagal rest. In shutdown, the body is heavy, numb, disconnected. The person lies in bed not from choice but from inability to mobilize. In ventral vagal rest, the body is relaxed, safe, restored. The person lies in bed from genuine pleasure in stillness.

The archetypal lens reveals deeper layers. Bed rotting represents regression to the Womb, but it is the womb as tomb: not the nurturing matrix from which one emerges renewed but the grave from which one cannot rise. This is the Wounded Child hiding from a world that feels too threatening, too demanding, too large. Hurkle-durkling, by contrast, represents the Innocent at rest: the part of self that can trust safety enough to let down vigilance, that knows periods of dormancy are natural and necessary.

The clinical question becomes: which state is this client actually experiencing? Are they choosing rest or fleeing into paralysis? Is the bed a sanctuary or a prison? The answer determines whether intervention should encourage mobilization or validate the need for genuine restoration.

Relationships: The Soul Projected

Limerence and Anima Possession

Limerence, coined by psychologist Dorothy Tennov in the 1970s, has experienced a dramatic resurgence in popular discourse. According to research published in the Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, limerence is defined as the obsessive attachment to a person in which there is an overwhelming longing for another person’s attention. This cognitive state is characterized as distinct from feelings associated with having a “crush” or being “in love” as, unlike in a crush, the feelings of intense longing come and go, driven primarily by uncertainty about reciprocation.

What distinguishes limerence from ordinary romantic attraction is its compulsive quality. The limerent person cannot stop thinking about the “Limerent Object.” They engage in elaborate fantasies of reciprocation. They interpret neutral behavior as coded messages of love or rejection. They experience physical symptoms: racing heart, sleeplessness, appetite changes. According to PMC research on limerence treatment, uncertainty is the driving force behind the development and maintenance of limerence. The greater the degree of uncertainty, the more intensely the individual ruminates about the LO.

The Jungian analysis is precise: limerence is classic Anima/Animus possession. The individual falls in love not with the actual other person but with the missing part of their own soul projected onto them. The limerent person who cannot stop thinking about their LO is not obsessed with an external human being; they are obsessed with their own unintegrated contrasexual energy, the feminine in the man or the masculine in the woman, externalized onto a convenient screen.

This explains why limerence so often targets unavailable objects: people who are already partnered, emotionally distant, geographically remote, or otherwise incapable of full relationship. The actual relationship would destroy the projection. What the limerent person unconsciously seeks is not union with the other but contemplation of the projected soul-image, and this contemplation requires that the other remain at a distance where fantasy can flourish uncontaminated by reality.

The projection of the “Golden Shadow,” the positive potential we have disowned, compounds the intensity. The LO seems to possess all the qualities we secretly wish we had: confidence, charisma, creative power, erotic magnetism. We worship them for holding our gold, never recognizing that what we adore is our own undeveloped capacity reflected back.

Treatment requires the slow, painful work of withdrawing the projection: recognizing that the godlike qualities attributed to the LO are actually seeds within the self awaiting cultivation. The cure for limerence is not finding a better object but reclaiming the projected soul.

The Ick and Neuroceptive Sentries

If limerence represents the dangerous inflation of romantic projection, “the ick” represents its sudden, often inexplicable collapse. One moment the person is attractive, interesting, full of promise; the next, something they do, often something trivial, triggers intense repulsion. The relationship, or potential relationship, is over.

According to research published in Personality and Individual Differences, people who are more prone to disgust, who hold others to high standards, or who score higher in narcissism are more likely to experience the ick. The study found that 64% of participants had experienced the ick at some point, with women significantly more likely than men to report the experience.

Clinical analysis reveals its connection to attachment: individuals with avoidant attachment styles may be more prone to experiencing “the ick” due to their sensitivity to potential relational flaws. Avoidant attachment style can also lead to a preference for casual relationships and a heightened sensitivity to signs of emotional unavailability, which may contribute to the sudden feeling of repulsion.

The Polyvagal interpretation frames the ick as neuroception in action: the nervous system’s pre-conscious evaluation of safety and compatibility. Sometimes the ick reflects genuine incompatibility detected at a level beneath conscious awareness. Sometimes it reflects the activation of defensive strategies as intimacy begins to feel threatening. The challenge lies in distinguishing between the two.

Archetypally, the ick functions as a sentry at the gates of intimacy. For those with secure attachment, the sentry operates with appropriate discrimination, alerting to genuine threats while allowing safe others to pass. For those with avoidant attachment, the sentry has been trained by early experience to treat all intimacy as threat. The slightest triggering stimulus, a gesture, a tone, a word, activates the alarm, and the gates slam shut.

The clinical work involves investigating the sentry’s protocols. What is it really defending against? What early experiences trained it to respond this way? Is the ick a message from genuine intuition, or is it the avoidant system protecting against the vulnerability that real connection requires?

Cultural and Seasonal: The Hero’s Journey

The Winter Arc and the Night Sea Journey

The “Winter Arc” trend reframes the dark months not as a pathology to be endured but as a sacred opportunity for transformation. Rather than fighting Seasonal Affective Disorder with light boxes and medication alone, Winter Arc practitioners lean into the darkness, treating winter as a natural period for introspection, discipline, and the confrontation of Shadow material.

The trend validates an archetypal truth that the biomedical model systematically ignores: human beings are seasonal creatures embedded in natural cycles. The relentless demand for year-round productivity, the expectation that summer energy can be sustained through February, contradicts biological reality. Animals hibernate. Plants go dormant. The insistence that humans should be exempt from cyclical rest represents cultural pathology, not mental health.

The mythological frame here is the Night Sea Journey, the hero’s descent into darkness that precedes rebirth. Jonah in the whale. Persephone in the underworld. Every wisdom tradition recognizes that certain transformations require darkness, that the seed must be buried before it can grow, that the death of the old self is the prerequisite for the emergence of the new.

The Hermit archetype governs this territory: the withdrawal from external engagement in service of inner illumination. The Hermit is not depressed; the Hermit is working at a level the extraverted world cannot see. The Winter Arc is the Hermit’s season, the time when the lantern is carried into the cave rather than onto the mountain.

This does not mean that Seasonal Affective Disorder is imaginary or that no intervention is warranted for winter suffering. It means that the framework matters. A client who understands their winter withdrawal as pathology will experience it differently than one who understands it as participation in a necessary cycle. The intervention may be identical, light therapy, vitamin D, maintained social connection, but the meaning transforms the experience.

The Problem with Pop Psychology

Having articulated the valid intuitions embedded in Gen Z’s therapeutic vocabulary, intellectual honesty requires acknowledging its dangers. The democratization of clinical language through social media has produced not only increased awareness but also significant pathology of its own.

The TikTok Diagnosis Pipeline

According to research from Johns Hopkins Medicine, approximately 25% of young people have self-diagnosed a mental health condition based on social media content. The mechanism is algorithmic: a user watches a video about “ADHD paralysis,” the platform detects engagement, the feed increasingly populates with ADHD content, and confirmation bias does the rest. Soon the user’s entire digital environment reinforces the narrative that they have this condition.

The problem is not that these self-diagnoses are always wrong. Many people do identify genuine conditions through social media exposure, conditions that might have gone unrecognized for years in a less psychologically literate era. The problem is that content creators, incentivized by engagement metrics rather than clinical accuracy, strip complex disorders of nuance. Common human experiences, disliking loud noises, procrastinating, feeling socially awkward, are presented as definitive symptoms of pathology.

This creates friction in the clinical room. Clients arrive not with symptoms to be explored but with firm diagnoses derived from sixty-second clips. Challenging these self-diagnoses risks rupturing the therapeutic alliance; accepting them uncritically risks colluding with pathologization of normal experience. The competent clinician treats self-diagnoses as valid data points about the client’s internal experience while gently introducing clinical differentiation, honoring the suffering while questioning the label.

The Weaponization of Therapy Speak

As clinical terms enter the vernacular, they lose precision and gain combative power. According to Thriveworks research on therapy speak, 38% of people feel “gaslighting” is misused, and notably, 25% of Gen Z themselves express fatigue with therapeutic terminology deployed as weapons.

“Gaslighting,” originally defined as a systematic dismantling of someone’s reality, now frequently describes any instance of disagreement or factual dispute. “Boundaries,” in the clinical sense rules for one’s own behavior, have been weaponized as ultimatums to control others. “Toxic,” a catch-all for any person or behavior that does not serve one’s immediate happiness, is deployed to justify ending relationships without the difficult work of conflict resolution.

This weaponization is particularly evident in “therapy speak” that masquerades as self-care while actually serving avoidance. “I’m protecting my peace” can mean genuine boundary-setting, or it can mean refusing to engage with any situation that produces discomfort. “That’s a trauma response” can validate genuine suffering, or it can pathologize every emotional reaction one wishes to avoid examining. “I need to do my own work first” can reflect genuine insight, or it can indefinitely defer the vulnerability of actual relationship.

The irony is profound: terminology developed to facilitate emotional growth becomes a defense against it. The very vocabulary of healing is recruited into the service of the wound.

The Political Economy of Mental Health Knowledge

| Player | Role in System | Economic Incentive | Impact on Practice |

| Elsevier / Publishers | “Landlords of Knowledge” | 30-40% Profit Margins | Limits clinician access to research; creates epistemic inequality. |

| NIMH / Gov. Agencies | Funders / Regulators | Political Safety / “Trust in Numbers” | Favors “measurable” biomedical research (e.g., STAR*D) over complex therapy. |

| BetterHelp / Talkspace | Gig Economy Platforms | Volume / Data Extraction | Commodifies the alliance; increases therapist burnout; prioritizes access over depth. |

| Insurance Companies | Payers | Cost Containment | Mandates manualized, short-term therapies; penalizes “unstructured” depth work.

|

The Bad Therapy Hypothesis

No analysis of Gen Z mental health is complete without engaging the intellectual backlash represented by works like Abigail Shrier’s “Bad Therapy” and Jonathan Haidt’s “The Anxious Generation.” These authors argue, with varying emphases, that the mental health industry is exacerbating the distress it claims to treat.

Shrier contends that by constantly asking children “How are you feeling?” and monitoring their emotional temperature, adults have made Gen Z hyper-vigilant and anxious. The accommodation of anxiety, allowing children to skip triggers rather than face them, prevents the exposure that would naturally resolve the anxiety. The result is iatrogenesis: healer-caused harm. She argues that some “trauma-informed” practice prejudges students who have experienced hardship as fragile and in need of blanket mental health interventions, while lowering expectations for their behavior and achievement.

Haidt chronicles how the shift to a phone-based childhood affects development. He notes that kids deprived of unsupervised physical play, with opportunity for low-cost mistakes and even some criticism and teasing, fail to develop interpersonal skills and resilience. He describes how the “Great Rewiring” of childhood, the transition from play-based to phone-based development between 2010 and 2015, coincided precisely with the spike in youth mental illness.

The critique deserves serious engagement. There is evidence that psychological debriefing immediately after trauma can interfere with recovery. There is evidence that excessive focus on emotional states can increase rather than decrease distress. There is evidence that therapeutic culture, broadly construed, may be pathologizing normal developmental challenges.

Yet the critique also risks swinging to an opposite extreme equally damaging. The argument that Gen Z is “fragile” rather than “traumatized” can minimize genuine suffering. The emphasis on resilience can become another demand placed on young people already overwhelmed by demands. The nostalgic invocation of previous generations who “just got on with it” ignores the documented mental illness that went untreated, the suicides that were covered up, the suffering that was endured in silence because no alternative existed.

The truth lies in dialectic. Gen Z faces objective stressors that previous generations did not: climate crisis, economic precarity, algorithmic manipulation of attention, the collapse of traditional meaning-making structures. They also exist in a cultural context that may amplify rather than contain these stressors: the valorization of mental illness on social media, the therapeutic industrial complex with its financial interest in expanding the client base, the replacement of community with consumption.

Both are true. The world has become genuinely harder, and the responses to that difficulty have sometimes made things worse. Effective treatment must acknowledge both realities rather than collapsing into either ideological pole.

What Gen Z Actually Wants from Therapy

Understanding what this generation is rejecting clarifies what they are seeking. The research reveals several consistent themes in how Gen Z approaches the therapeutic relationship, themes that challenge traditional clinical assumptions.

The Death of the Blank Slate

The historical ideal of the therapist as a “blank slate,” neutral, opaque, and objective, is effectively dead for this generation. Gen Z demands authenticity and transparency. A therapist’s political neutrality is often viewed as complicity in systemic oppression.

According to research, Gen Z clients view the first session as an interview of the therapist. They ask direct questions about the therapist’s values, lived experiences, and approach to power dynamics. Green flags include being “real” (rejecting the blank slate persona), understanding internet culture without asking for explanations, transparency about the therapist’s own values, and admitting when they do not know something. Red flags include excessive silence (perceived as judgment), immediate pathologizing of behavior, or refusing to answer questions about stance on social justice issues.

This shifts the power dynamic of therapy. The client is the interviewer, and the therapist is the applicant. Gen Z approaches therapy as a collaboration between equals, demanding a “human” connection before a “clinical” one.

The Vibe Check and Cultural Alignment

Gen Z performs what they call a “vibe check,” an intuitive assessment of the therapist’s authenticity, safety, and cultural alignment. For BIPOC and LGBTQ+ Gen Z, “cultural competence” is the baseline expectation, but “cultural humility” and lived experience are the gold standards.

Minority Gen Z clients are acutely aware of how the medical system has historically pathologized their communities. They seek therapists who understand the nuances of code-switching, intergenerational trauma, and the specific anxieties of existing in a marginalized body without needing the client to educate them. With nearly 25% of Gen Z identifying as queer, there is massive demand for affirmative care that can navigate complex, intersecting identities. “Neutrality” on queer issues is often interpreted as hostility.

This has led to the proliferation of niche directories: Therapy for Black Girls, Latinx Therapy, Asian Mental Health Collective, Inclusive Therapists. These platforms are not just search tools; they are signals of safety and community validation.

Social Justice Counseling

Gen Z favors what the American Counseling Association terms “Social Justice Counseling,” a modality that recognizes issues of power, privilege, and oppression as central to client conceptualization.

Instead of asking “What is wrong with you?” (internal pathology), the therapist asks “What has happened to you?” and “How is the system impacting you?” (external oppression). This reduces shame. It frames anxiety not as a chemical imbalance but as a rational response to an unjust world. For Gen Z, this externalization is crucial for maintaining self-worth in a world they perceive as hostile.

The Somatic Turn

Gen Z is driving what might be called a “Somatic Turn” in psychology. Having absorbed the lesson that “The Body Keeps the Score,” they are demanding therapies that address the physiological roots of trauma, not just the cognitive ones.

“Nervous System Regulation” has become a dominant keyword in Gen Z wellness. Concepts like “fight, flight, freeze, fawn” and “ventral vagal state” are common knowledge. Gen Z clients explicitly ask for help “regulating their nervous system” or moving out of “dorsal vagal shutdown.” They want physical tools they can employ in real-time to alter their physiological state, not just insights they can contemplate retrospectively.

There is correspondingly high demand for EMDR, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, and other non-verbal trauma therapies. EMDR does not require the client to verbally retell the detailed story of their trauma, which can be re-traumatizing and exhausting. It focuses on the memory and the body sensation. For a generation overwhelmed by “trauma dumping,” this contained, structural, and efficient approach is highly attractive.

The Integration of the Mystical

In a development that surprises many clinicians, Gen Z is integrating “mystical” practices like Tarot and Astrology into their mental health frameworks. This is typically not a rejection of science but an adoption of narrative structures. Tarot cards provide a set of archetypes, The Tower, The Hermit, The Fool, that help Gen Z articulate their feelings when clinical language fails.

Research indicates that 51% of young people engage in Tarot or fortune-telling, often viewing it as complementary to therapy rather than a replacement. If a client says “I’m in my hermit era,” the culturally competent therapist understands this as a need for withdrawal and introspection, utilizing the client’s own metaphor to build alliance rather than correcting them.

This mystical integration connects to the broader demand for psychospiritual care, therapy that acknowledges the soul or spirit as part of the self without imposing religious dogma. Gen Z is highly secular in terms of institutional affiliation but deeply “Spiritual But Not Religious.” They want a spirituality that is “gritty” and capable of holding space for trauma and social injustice, not the “good vibes only” spiritual bypassing that avoids facing unresolved emotional issues.

The Different Needs of Gen Z Men

While the dominant narrative of Gen Z mental health is often female-coded, emphasizing anxiety, talk therapy, and emotional vulnerability, Gen Z men are undergoing a distinct and often overlooked evolution. They are statistically the most at risk for suicide, yet they are the most resistant to the “therapy speak” culture.

The Rejection of “Feminized” Care

Gen Z men often perceive traditional psychotherapy, with its emphasis on vulnerability, sitting still, and “talking it out,” as a feminine domain. They may feel “pathologized” by the clinical gaze or uncomfortable with the passive role of the “patient.”

There is a massive resurgence of Stoic philosophy among young men, popularized by authors like Ryan Holiday. They are drawn to the idea of emotional control, resilience, and discipline rather than emotional expression. Apps like Mental frame mental health as “training the mind” rather than “healing the heart.”

Coaching Over Therapy

Young men are increasingly bypassing “therapists” in favor of “coaches.” The reframing matters: “Coaching” implies you have potential to be optimized. “Therapy” implies you are broken and need fixing.

Coaching is future-oriented, goal-driven, and directive. It aligns with the “self-optimization” culture prevalent in male digital spaces. Gen Z men are willing to pay for “performance coaching” to address their anxiety, viewing it as a tool for success rather than a treatment for illness.

Brotherhood and Side-by-Side Vulnerability

Organizations like The Phoenix, a sober active community, have demonstrated effective approaches to men’s mental health. They do not ask men to sit in a circle and share feelings. They ask men to lift weights, climb mountains, or run together.

“Side-by-side” interaction reduces the intensity of direct eye contact, which can feel confrontational, and allows vulnerability to emerge organically during physical exertion. While Gen Z men are trying to break out of rigid masculinity, they still crave brotherhood and competence. They want spaces where they can be vulnerable without feeling weak. Peer support networks and “Men’s Groups” are filling this gap more effectively than clinical settings.

Why Psychology Needs Story

The deeper critique embedded in Gen Z’s therapeutic vocabulary, often implicit rather than explicit, concerns the absence of meaning from the biomedical model. A brain chemistry imbalance does not explain why one suffers. A neurotransmitter deficiency does not locate one’s distress in a narrative of significance. The biomedical model tells the patient what is wrong but cannot tell them why it matters or what transformation might mean.

This is not a minor aesthetic preference. Human beings are meaning-making creatures. We do not merely experience events; we experience events as meaningful, as part of stories that have beginnings and trajectories and possible endings. Viktor Frankl, writing from the Nazi concentration camps, observed that those who survived were often those who could locate their suffering within a meaningful frame, who had a “why” that could endure any “how.”

The biomedical model provides no why. It reduces the individual to a collection of mechanisms that have malfunctioned, removing agency, stripping context, flattening the complexity of human existence into diagnostic categories and medication regimens. This is not healing; it is management. It may reduce symptoms, but it cannot restore meaning.

Gen Z’s hunger for story expresses itself in multiple ways. The popularity of attachment theory reflects the desire to locate present difficulties in a narrative extending back to earliest relationships. The embrace of nervous system language reflects the desire to understand the body as a character in one’s story rather than merely a machine one inhabits. The fascination with archetypes reflects the desire to see one’s struggles as participation in universal human patterns rather than idiosyncratic malfunction.

This hunger is healthy. It represents the psyche’s instinct for its own medicine. What is needed is not the elimination of biological understanding but its integration into a larger frame, one that honors both mechanism and meaning, both neurotransmitter and narrative.

This is what I mean by bio-mythology: a therapeutic approach that brings together the insights of contemporary neuroscience with the wisdom of depth psychology, that tracks the pathways of the vagus nerve while also tracing the hero’s journey, that maps brain waves while also mapping archetypal territories. The body keeps the score, yes, and the score it keeps is a story.

Toward a New Paradigm

What would a therapy adequate to this generation’s needs actually look like? Several principles emerge from the foregoing analysis.

First, it must be somatic. The era of the “talking cure” as the primary modality is ending. Gen Z understands intuitively what neuroscience has confirmed: trauma lives in the body, and the body must be involved in healing. Modalities that work with autonomic states, that address subcortical processing, that engage the nervous system directly, will increasingly displace purely cognitive approaches.

Brainspotting, EMDR, and other approaches that access subcortical brain regions where trauma is stored allow processing to occur beneath the level of verbal narrative. qEEG brain mapping reveals the brain’s electrical patterns, providing objective data about which networks are dysregulated and how intervention might proceed. These are not alternatives to insight but foundations upon which insight can build.

Second, it must be narrative. Symptom reduction is not enough. Gen Z seeks understanding of who they are and how they came to suffer and what transformation means. This requires therapeutic approaches that situate the individual’s distress within larger frames of meaning: developmental narratives, archetypal patterns, mythological structures that dignify suffering by connecting it to universal human experience.

The client who understands their anxiety as dorsal vagal shutdown resulting from early attachment disruption experiences that anxiety differently than one who understands it as a chemical imbalance. Both framings may be accurate, but the narrative framing provides agency, context, and the possibility of meaningful transformation rather than mere management.

Third, it must be integrative. The separation of biological, psychological, and social factors that characterizes the biomedical model does not reflect lived experience. Gen Z knows this because they live it: their anxiety is simultaneously a nervous system state, a psychological pattern, and a response to social conditions. Treatment that addresses only one dimension will necessarily be incomplete.

This requires clinicians trained in multiple modalities and frameworks, able to track autonomic states while also tracking archetypal dynamics, able to discuss neurotransmitters while also discussing meaning. The specialist model, in which one professional addresses the brain while another addresses the psyche while another addresses the social context, fragments what must be held whole.

Fourth, it must be culturally responsive. Gen Z is the most diverse generation in American history, and their diversity extends beyond demographics to worldview. The standard Western model of individual psychotherapy does not resonate equally across all populations. Some clients need community-based intervention; some need spiritually integrated care; some need approaches that acknowledge systemic oppression as a legitimate cause of distress rather than pathologizing the response to injustice.

Asking “What has happened to you?” and “How is the system impacting you?” rather than “What is wrong with you?” reduces shame and validates the external dimensions of internal distress. For a generation that experiences collective trauma, whether from climate anxiety, political polarization, or the algorithms that manipulate their attention, this reframing is not optional.

Fifth, it must speak their language. The glossary provided earlier is not merely academic. When a client describes “crashing out,” the competent clinician does not insist on “emotional dysregulation.” When a client reports being in “functional freeze,” the clinician does not correct them to “depression with atypical features.” Language matters. Meeting clients in their vocabulary, while gently introducing more precise concepts, builds alliance and demonstrates respect.

This does not mean accepting every self-diagnosis uncritically or colluding with the weaponization of therapy speak. It means recognizing that pop psychology vocabulary often contains valid intuitions poorly articulated, and that the clinical task involves extracting the truth from the trend.

CoThe Soul in the Machine Age

Generation Z arrives at therapy having learned one great truth that previous generations often missed: psychological suffering is real, it has causes, and it can be addressed. This represents genuine progress. The destigmatization of mental health treatment means that millions who would have suffered in silence now seek help.

But they arrive also having absorbed a model that reduces them to malfunctioning machines, that offers chemical intervention for existential distress, that promises cure through adjustment of neurotransmitters. And this model has failed them, as the mounting evidence of their unprecedented distress confirms.

The pop psychology vocabulary they speak, for all its imprecision and potential for misuse, represents a groping toward something the biomedical model cannot provide: a psychology that includes the body as a narrative agent, that situates individual suffering within collective patterns, that offers meaning as well as mechanism. When they talk about “dorsal vagal shutdown” and “glimmers” and “the Ick,” they are reaching for a framework that honors their complexity as embodied, storied beings.

The task of contemporary psychotherapy is to meet this reaching with adequate response. This means integrating the genuine advances of neuroscience, the brain mapping and the nervous system regulation and the understanding of subcortical processing, with the wisdom of traditions that understood the psyche as ensouled, as participating in patterns larger than individual biography, as requiring transformation rather than mere repair.

The machine metaphor has exhausted itself. What is needed now is a return to what the ancients knew: that healing requires meaning, that the body tells stories, that we are heroes on journeys even when we have forgotten the path. Gen Z knows this in their bones, which is why they keep searching for vocabularies that might express it. The clinicians who can provide such vocabularies, who can speak the language of both neuroscience and mythology, will be the ones adequate to this generation’s genuine needs.

The nervous system is a storyteller, and the story it tells matters. Let us learn to tell better stories.

Bibliography

American Community Media. (n.d.). Gen Z mental health crisis requires cultural understanding and proven treatments. https://americancommunitymedia.org/health-care/gen-z-mental-health-crisis-requires-cultural-understanding-and-proven-treatments/

American Counseling Association. (n.d.). Conceptualizing diagnosis through a social justice lens. Counseling Today. https://www.counseling.org/publications/counseling-today-magazine/article-archive/article/legacy/conceptualizing-diagnosis-through-a-social-justice-lens

American Psychological Association. (2022, March). Navigating thorny topics in therapy. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/03/career-navigating-therapy

App Store. (n.d.). Mental: AI therapy & coaching. Apple. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/mental-ai-therapy-coaching/id6444276517

Barton, K. (n.d.). Let glimmers of meaning bring shine to your life. Swedish Health Services. https://blog.swedish.org/swedish-blog/let-glimmers-of-meaning-bring-shine-to-your-life

Blueprint. (n.d.). Gen Z therapy: Understanding and engaging the next generation of clients. https://www.blueprint.ai/blog/gen-z-therapy

Brainz Magazine. (n.d.). Millennial thera-preneurs: The balancing act between being a therapist & business owner. https://www.brainzmagazine.com/post/millennial-thera-preneurs-the-balancing-act-between-being-a-therapist-business-owner

Brown University School of Public Health. (2025, October 29). Beyond therapy: How a student-built app is using AI to update addiction recovery for Gen Z. https://sph.brown.edu/news/2025-10-29/peerakeet-app-recovery

Calm. (n.d.). Glimmers: what they are, why they matter, and 5 ways to find them. https://www.calm.com/blog/glimmers

CBC Radio. (n.d.). Mental health & TikTok. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/spark/mental-health-tiktok-1.7242717

Coach Training EDU. (n.d.). Life coaching vs. therapy: Understanding the key differences and career opportunities. https://www.coachtrainingedu.com/blog/life-coaching-vs-therapy-understanding-the-key-differences-and-career-opportunities/

Colocho, A. (2025, July 28). Gen Z and telehealth. eHealth Virginia. https://www.ehealthvirginia.org/gen-z-and-telehealth/

Cutler, D. (n.d.). A teacher’s quest to foster resilience and combat fragility in Generation Z. Medium. https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/a-teachers-quest-to-foster-resilience-and-combat-fragility-in-generation-z-bb63ce5b786f

Equimundo. (2025). State of American men 2025. https://www.equimundo.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/State-of-American-Men-2025.pdf

FasPsych. (n.d.). AI in mental health 2025: LLMs overtaking apps. https://faspsych.com/blog/ai-mental-health-trends-2025-llms-vs-apps/

Fink, J. L. W. (2024, March). An unstoppable force. Counseling Today. https://www.counseling.org/publications/counseling-today-magazine/article-archive/article/march-2024/an-unstoppable-force

Frontiers in Public Health. (2025). Flourishing during stages of substance use recovery among members of The Phoenix: a United States sober-active community. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1683975/full

Global Coalition for Youth Mental Health. (2025). Perception of youth mental health report 2025. UNICEF. https://www.youthmentalhealthcoalition.org/gen-z

Global Wellness Institute. (2025, April 2). AI initiative trends for 2025. https://globalwellnessinstitute.org/global-wellness-institute-blog/2025/04/02/ai-initiative-trends-for-2025/

Grand Canyon University. (n.d.). Life coach vs. therapist: What are the differences? https://www.gcu.edu/blog/psychology-counseling/life-coach-vs-therapist-what-are-differences

Harbor Mental Health. (2025, July 1). Mental health and social media: How TikTok and Instagram are shaping self diagnosis culture. https://harbormentalhealth.com/2025/07/01/mental-health-and-social-media-self-diagnosis/

Harmony Healthcare IT. (2025). State of Gen Z mental health. https://www.harmonyhit.com/state-of-gen-z-mental-health/

Headspace. (n.d.). Online mental health and wellness coaching. https://www.headspace.com/coaching

Health Exec. (2025, September 3). AI lag primary care. https://healthexec.com/newsletter/2025-09-03/ai-lag-primary-care-partner-voice-gen-z-job-angst-ai-anti-therapy-animal-testing-phaseout-more

Horowitz, S. (n.d.). Harmful therapy for children and the seduction of parents. National Association of Scholars. https://www.nas.org/academic-questions/38/3/harmful-therapy-for-children-and-the-seduction-of-parents

Independent Institute. (2025, September 20). Understanding and saving Gen Z to save America. https://www.independent.org/article/2025/09/20/understanding-and-saving-gen-z-to-save-america/

Insights. (n.d.). Why are millennials turning to tarot readings for career advice? https://insights.made-in-china.com/Why-Are-Millennials-Turning-to-Tarot-Readings-for-Career-Advice-The-Surprising-Truth-Behind-the-Trend_btkAaKmjVElR.html

It’s OK. (n.d.). Does your therapist have these green flags? Medium. https://medium.com/@ItisOK/does-your-therapist-have-these-green-flags-dc2544adaab2

Kaplan, A. (2025, August 31). The weaponizing of therapy speak. Waikiki Health. https://waikikihealth.com/the-weaponizing-of-therapy-speak/

Katzenstein, J. (2023, August). Social media and self-diagnosis. Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/articles/2023/08/social-media-and-self-diagnosis

Liberty University. (n.d.). Exploring spiritual principles and mental health. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=8693&context=doctoral

Mack, E. (2024, November 14). I offer free online therapy to teens. Here’s what I’m seeing — and why it matters. Chalkbeat New York. https://www.chalkbeat.org/newyork/2024/11/14/nyc-teenspace-talkspace-here-is-how-i-approach-text-based-therapy/

Mahdi, M., Azhari, A., & Yusof, M. H. M. (2025, June 30). Psychospiritual challenges of Gen Z in the digital era: The role of Islamic guidance and counselling. JROH: Jurnal Obat Hati. https://journal.ccula.org/index.php/jroh/article/view/65

McKinsey Health Institute. (n.d.). Gen Z mental health: The impact of tech and social media. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/mhi/our-insights/gen-z-mental-health-the-impact-of-tech-and-social-media

Meridian Counseling. (n.d.). The dangerous drift: Mental health professionals, political violence, and the loss of empathy. https://www.meridian-counseling.com/blog/the-dangerous-drift-mental-health-professionals-political-violence-and-the-loss-of-empathy

Meyer, A. (2024, September 30). How Gen Z is shaping a new era of mental-health care. MSU Denver RED. https://red.msudenver.edu/2024/how-gen-z-is-shaping-a-new-era-of-mental-health-care/

National Catholic Reporter. (n.d.). Study: Gen Z doubles down on spirituality, combining tarot and traditional faith. https://www.ncronline.org/news/study-gen-z-doubles-down-spirituality-combining-tarot-and-traditional-faith

National Directory for Conservative Therapists. (n.d.). National directory for conservative therapists & mental health professionals. https://www.conservativetherapists.com/

National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). Neurodiversity, advocacy, anti-therapy. PubMed Central. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11285098/

National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). The ability of AI therapy bots to set limits with distressed adolescents. PubMed Central. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12360667/

National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). Unmasking therapy-speak. PubMed Central. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12583418/

Pacific Oaks College. (2025, October 27). Gen Z’s view on mental health. https://www.pacificoaks.edu/voices/blog/gen-z-view-on-mental-health/

Psychology Today. (2022, August 5). Queer or questioning? This one is for you. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/do-your-own-think/202404/queer-or-questioning-this-one-is-for-you

Psychology Today. (2025). TikTok therapy: How Gen Z’s trend is reshaping mental health. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-human-algorithm/202503/tiktok-therapy-how-gen-zs-trend-is-reshaping-mental-health

Quest Behavioral Health. (n.d.). How social media affects mental health. https://questbehavioralhealth.com/how-social-media-affects-mental-health/

Religion & Liberty Online. (n.d.). Raise your own damn kids. https://rlo.acton.org/archives/125368-raise-your-own-damn-kids.html

Rowan Center for Behavioral Medicine. (n.d.). The Gen Z stare: Social anxiety and new communication styles. https://rowancenterla.com/the-gen-z-stare-social-anxiety-and-new-communication-styles/

Skeptic Research Center. (n.d.). Mental illness, political ideology, and holding false beliefs. https://research.skeptic.com/mental-illness-political-ideology-and-holding-false-beliefs/

Stand Together. (n.d.). 5 ways peer support networks are changing mental health care. https://standtogether.org/stories/health-care/ways-peer-support-networks-are-changing-mental-health-care

The Brink. (n.d.). Peer circles, not couch sessions: Gen Z’s quiet revolt against therapy. https://www.thebrink.me/peer-circles-not-couch-sessions-gen-zs-quiet-revolt-against-therapy/

The Jed Foundation. (n.d.). What to expect in 2025: New year’s trends in youth mental health. https://jedfoundation.org/what-to-expect-in-2025-new-years-trends-in-youth-mental-health/

The Skeptic. (2021, July). Why millennials and Gen Z are turning to tarot as a form of “therapy”. https://www.skeptic.org.uk/2021/07/why-millennials-and-gen-z-are-turning-to-tarot-as-a-form-of-therapy/

TherapySEO. (n.d.). The complete list of counselling directories. https://www.therapieseo.com/blog/the-complete-list-of-counselling-directories

Thriveworks. (2025). Thriveworks 2025 pulse on mental health report. https://thriveworks.com/help-with/research/pulse-on-mental-health-report/

Thriveworks. (n.d.). Therapy speak survey. https://thriveworks.com/help-with/research/therapy-speak-survey

Thriving Center of Psychology. (n.d.). Gen Z & millennial therapy statistics. https://thrivingcenterofpsych.com/blog/gen-z-millennial-therapy-statistics/

University of the Cumberlands. (n.d.). Is physical therapy the right fit for Gen Z? Here’s why the answer is yes. https://www.ucumberlands.edu/blog/physical-therapy-right-fit-gen-z-heres-why-answer-yes

Washington Psychiatric Society. (2025, December 9). 87% of surveyed millennials and Gen Z engage in mindfulness or spiritual practices, but only 31% talk about it. https://www.dcpsych.org/

World Economic Forum. (2024, October). How AI could expand and improve access to mental health treatment. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/10/how-ai-could-expand-and-improve-access-to-mental-health-treatment/

Joel Blackstock, LICSW-S, is the Clinical Director of Taproot Therapy Collective in Hoover, Alabama. He specializes in complex trauma treatment using advanced modalities including Brainspotting, EMDR, Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT), and qEEG brain mapping. For more information about integrative, depth-oriented treatment, contact Taproot Therapy Collective.

0 Comments