The Hidden Conversation Between Body and Brain

For decades, mainstream psychotherapy has operated under a fundamental assumption: that emotional healing flows primarily from the top down. The prevailing belief has been that if we can change our thoughts, we can change our feelings. Cognitive approaches have dominated the landscape, teaching clients to identify distorted thinking, challenge irrational beliefs, and reconstruct healthier cognitive frameworks. While these approaches have undeniable value for certain conditions, they rest on an incomplete understanding of how emotions actually arise and persist in the human nervous system.

The truth, etched into the very architecture of our neurobiology, tells a different story. The pathways that carry information from the body to the brain are anatomically and functionally more dominant than those that carry commands from the brain to the body. This fundamental asymmetry has profound implications for how we understand emotional dysregulation and, more importantly, how we treat it. When we examine the subcortical brain and its relationship to our conscious experience, we discover that the body does not merely respond to the brain’s commands; in many cases, the body leads, and the brain follows.

This article presents a comprehensive neurobiological argument for why somatic and brain-based therapies such as Somatic Experiencing, Brainspotting, EMDR, Emotional Transformation Therapy, and myofascial release approaches are often more effective than purely cognitive interventions for healing persistent emotional dysregulation and trauma. The evidence converges on a single, powerful conclusion: to change persistent feelings, we must often first change the persistent signals that the body broadcasts to the brain.

The Architecture of Feeling: Understanding Afferent and Efferent Pathways

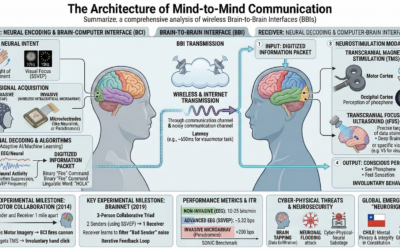

The human nervous system maintains a constant dialogue between the brain and the body. This communication flows in two directions through distinct pathways. The efferent nervous system carries signals from the brain outward to the body’s muscles and glands, enabling action and response. This is the pathway through which cognitive intentions become physical reality—the neural infrastructure of “doing.” The afferent nervous system, by contrast, constitutes the ascending current of information, carrying signals from the periphery of the body to the central nervous system. This is the pathway through which the brain senses both the external world and its own internal environment. (Study.com: Afferent & Efferent Divisions of the Nervous System)

The afferent system can be divided into two critical subdivisions. The somatic afferent system conveys information from the skin, skeletal muscles, joints, and tendons, providing the brain with continuous data about touch, temperature, pain, and proprioception—the position and movement of the body in space. The visceral afferent system conveys information from the internal organs, monitoring variables such as internal pressure, organ volume, chemical composition, and pain. This visceral sensing, known as interoception, is a critical source of information that underpins our most basic feelings of well-being or distress. (Frontiers in Psychology: Attenuated Sensitivity to the Emotions of Others by Insular Lesion)

Here is where the research becomes particularly compelling for understanding trauma and emotional dysregulation. Historically, the study of emotion has been heavily skewed toward a top-down, efferent conceptualization, which frames emotion as a multi-component response orchestrated by the brain and sent outward to the body. The alternative, afferent-based view—that subjective emotional feelings are, in large part, a reflection of the brain reading the body’s physiological changes—has been comparatively under-researched, creating what researchers have called a significant “conceptual blind spot” in both scientific and popular understandings of emotion. (ResearchGate: A Two-Way Road: Efferent and Afferent Pathways of Autonomic Activity in Emotion)

The Vagus Nerve: Anatomical Evidence for Body Primacy

The most striking evidence for the primacy of bottom-up signals comes from the anatomy of the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve, or cranial nerve X, is the longest and most complex of the cranial nerves and serves as the primary component of the parasympathetic nervous system. It is the main conduit through which the brain communicates with and regulates the heart, lungs, and digestive tract. Given its role in promoting the “rest and digest” state, one might assume it is primarily an efferent, or command, nerve. (Frontiers in Psychiatry: Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis)

However, anatomical studies have unequivocally shown the opposite to be true. The vagus nerve is composed of between 80% and 90% afferent fibers. (Wikipedia: Vagus Nerve) This single anatomical statistic is a cornerstone of an embodied understanding of emotion. It means that the primary nerve responsible for maintaining the body’s state of calm and safety is overwhelmingly dedicated to listening to the body, not to commanding it. The neural highway connecting the brain to the core visceral organs is, by a factor of at least four to one, an ascending sensory pathway.

The dialogue between the brain and the body is not a balanced conversation; the body’s broadcast is anatomically privileged, possessing a far greater bandwidth for sending information up to the brain than the brain has for sending commands down. While science and popular culture have focused on the 10-20% of the conversation representing the brain’s top-down control, they have largely ignored the implications of the 80-90% representing the body’s constant, bottom-up feedback. The body does not just talk to the brain—it shouts, while the brain, in many instances, can only whisper back.

The Body’s Broadcast: How Posture and Visceral States Shape Emotion

The vagus nerve serves as the central channel for interoception—the sense of the internal state of the body. Its “wandering” path from the brainstem down through the neck and into the thorax and abdomen allows it to innervate and monitor nearly every major organ. Vagal afferent fibers terminate in specialized receptors that detect mechanical and chemical changes within the organs, including mucosal mechanoreceptors, chemoreceptors, and tension receptors in the esophagus, stomach, and intestines. This constant stream of data provides the brain with a detailed, real-time map of visceral function.

This information travels up the vagus nerve to a critical relay station in the brainstem called the Nucleus Tractus Solitarius (NTS). From the NTS, interoceptive information is projected to higher brain centers fundamental to emotional processing, including the thalamus, the amygdala, and the insular cortex. Research has demonstrated that stimulating vagal afferent fibers directly influences the brain’s monoaminergic systems—the networks that use neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine, which are critically involved in regulating mood and anxiety. This provides a concrete mechanism explaining why gut health can profoundly impact mental health. The “gut feeling” is a literal, neurobiological event.

Parallel to the visceral broadcast of the vagus nerve is the somatic broadcast of the musculoskeletal system, communicated most clearly through posture. Contemporary neuroscience reframes posture not as a simple matter of biomechanics or habit, but as a direct, dynamic, and continuous neurological expression of the brain’s assessment of its environment and internal state. (Next Level Neuro: The Hidden Brain Science About Your Posture) Postural patterns are not passive; they are active outputs generated by the brain, often as a protective strategy in response to perceived threat.

The link between emotion and posture is mediated by a network of shared neuroanatomical connections within the central nervous system, particularly involving the limbic system. (Frontiers in Neurology: Emotional State as a Modulator of Autonomic and Somatic Responses) This relationship is profoundly bidirectional. An emotional state like fear or anxiety can trigger physiological arousal that leads to changes in postural sway and muscle tension. Conversely, deliberately adopting a specific posture can directly influence one’s emotional state. Studies have demonstrated that an upright, expansive posture can increase feelings of pride and confidence, improve mood, and make it easier to recall positive memories, whereas a slumped, constrictive posture is consistently associated with feelings of sadness, fatigue, hopelessness, and an increased focus on negative memories. (Psychology Today: Your Physical Posture Could Change Your Mood)

Polyvagal Theory: A Framework for Understanding Survival States

Polyvagal Theory, developed by Dr. Stephen Porges, provides an elegant and powerful framework for understanding how postural and visceral states are organized by the nervous system as adaptive survival responses. (EBSCO Research Starters: Polyvagal Theory) The theory’s central concept is neuroception: the nervous system’s continuous, subconscious process of scanning for cues of safety, danger, and life-threat, both in the external environment and within the body itself. (PMC: Polyvagal Theory: Current Status, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions) Our autonomic state, and by extension our posture, is a direct reflection of our neuroception at any given moment.

Porges proposes that the autonomic nervous system is organized into a three-part hierarchy, with each level representing a different evolutionary strategy for survival. The Ventral Vagal Complex (Social Engagement System) is the most recently evolved system, unique to mammals. When our neuroception detects cues of safety, this system is active, promoting feelings of calm, connection, and social engagement. The corresponding posture is typically upright, open, and relaxed. The Sympathetic Nervous System (Mobilization) is an older system responsible for the “fight-or-flight” response, leading to increased heart rate, muscle tension, and vigilance. The Dorsal Vagal Complex (Immobilization) is the most primitive branch, triggering a shutdown or “freeze” response when neuroception detects a situation of inescapable life-threat. The physical signature of this state is a collapsed, slumped posture with decreased muscle tone and shallow breathing.

This framework allows for a profound reinterpretation of chronic postural patterns as understood in Somatic Trauma Mapping. A person with a persistently slumped, forward-head posture is not simply exhibiting poor habits. Their nervous system is actively maintaining a dorsal vagal state of shutdown. This is not a passive structural issue but an active, persistent, and neurologically maintained survival state. The body, through its posture, is continuously broadcasting an afferent signal of helplessness, defeat, and life-threat to the brain. Consequently, the brain interprets this relentless signal and generates the congruent emotions: hopelessness, depression, fatigue, and despair.

One cannot simply “think” their way out of a dorsal vagal state, because the very physical architecture of that state—the posture itself—is a primary driver of the afferent feedback loop that convinces the brain the threat is ongoing and inescapable. To change the persistent feeling, one must first interrupt the persistent survival signal being broadcast by the body.

The Insular Cortex: Where Body Becomes Feeling

The body’s broadcast, carried by the vast network of afferent fibers, does not terminate in the brainstem. It continues its journey upward, into the core structures of the brain where raw physiological data is meticulously processed, integrated, and ultimately transformed into the rich tapestry of conscious emotional experience. Deep within the lateral sulcus of the brain lies the insular cortex, a region now widely recognized as the primary neural substrate for interoception—the brain’s perception of the body’s internal state. (ResearchGate: The Insular Cortex: An Interface Between Sensation, Emotion, and Cognition)

The insula is not merely a passive recipient of information; it actively integrates and interprets it. Research indicates a clear functional gradient within the insula, with information flowing in a posterior-to-anterior direction. The posterior insula acts as the primary sensory cortex for the body’s interior, receiving the raw interoceptive data that has ascended from the periphery via the brainstem’s NTS. This raw data is then relayed forward to the mid- and anterior insula, where it is integrated with information from other brain regions, including the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. It is here, in the anterior insular cortex, that this integrated information is thought to give rise to conscious awareness.

This process is fundamental to our sense of self. It is proposed that the re-representation of interoceptive information in the anterior insular cortex generates the template for “feeling” and substantiates what has been termed the “sentient self”—our continuous, moment-to-moment awareness of being a living, embodied organism. This is not an abstract cognitive construct but a deeply physical one, grounded in the perception of our own physiology. The profound importance of the insula in this process is underscored by neuropsychological studies. Patients with lesions or damage to the insular cortex often exhibit attenuated emotional sensitivity and impaired emotion recognition, providing causal evidence that the ability to accurately perceive one’s internal bodily state is a prerequisite for a full and nuanced emotional life. This is why developing interoceptive awareness through practices like mindfulness meditation is so powerful for emotional regulation.

The Amygdala’s Bottom-Up Override

While the insula is crucial for the conscious experience of feeling, another key structure, the amygdala, plays a vital role in the rapid, often unconscious, appraisal of the emotional significance of bodily states. (MDPI: Understanding Emotions: Origins and Roles of the Amygdala) A key feature of the amygdala is its function as a convergence zone for both exteroceptive (external world) and interoceptive (internal body) information. It receives sensory input from the outside world, but it also receives direct projections from the interoceptive pathways originating in the NTS.

Classic studies in conscious, freely moving animals demonstrated that a majority of single neurons in the amygdala respond to both external sensory stimuli (optic, acoustic, tactile) and internal, interoceptive stimuli (such as changes in blood pressure), highlighting its role as a powerful integrator of internal and external worlds. (PubMed: Responses of Single Neurons in Amygdala to Interoceptive and Exteroceptive Stimuli) This anatomical arrangement means the amygdala is constantly “listening” to the body’s internal state. A sudden increase in heart rate, a clenching in the gut, or a change in breathing patterns—all signaled via afferent pathways—can directly activate the amygdala and trigger a fear or anxiety response, even in the absence of an identifiable external threat.

Furthermore, the amygdala can be activated in a “bottom-up” fashion by emotionally significant stimuli, often before these stimuli are consciously perceived. (Frontiers in Psychology: Amygdala Response to Emotional Stimuli without Awareness) This suggests that the amygdala performs a quick appraisal of incoming sensory data to determine its survival relevance. When this rapid appraisal is driven by strong interoceptive signals of arousal or distress, it can initiate a full-blown emotional and physiological response that precedes, and can subsequently overpower, any slower, more deliberate cognitive assessment from the prefrontal cortex. This is why Brainspotting and other subcortical approaches that directly access these lower brain structures can be so effective in releasing traumatic activation.

Damasio’s Somatic Marker Hypothesis: How Gut Feelings Guide the Mind

The Somatic Marker Hypothesis (SMH), proposed by neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, provides a compelling framework for understanding how interoceptively-driven feelings are not merely byproducts of emotion but are essential components of rational thought and decision-making. (Wikipedia: Somatic Marker Hypothesis) The hypothesis posits that as we navigate the world, our experiences—particularly those with strong emotional outcomes—create associated physiological changes in the body. These changes, which can include shifts in heart rate, gut motility, muscle tension, and posture, are termed “somatic markers.”

According to the SMH, these somatic markers are encoded and linked to the memory of the event that caused them, a process mediated by the amygdala and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. When we later encounter a similar situation, the brain reactivates a representation of that somatic marker, often before any conscious deliberation has taken place. This reactivation creates a “gut feeling” or an intuition that biases our decision-making. (Frontiers in Neuroscience: Bittersweet Memories and Somatic Marker Hypothesis) Evidence from patients with damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, who often show severe impairments in real-world decision-making despite intact intellect, supports this model.

The SMH powerfully integrates the afferent feedback loop into the core of cognition. It argues that the body’s feedback is not just something to be felt, but something to be used as critical data for navigating the world. This has profound implications for understanding enmeshed emotion. A chronic, maladaptive posture and the associated visceral state will continuously generate a stream of negative somatic markers. These markers will then bias all subsequent cognitive processes—thoughts, interpretations, and decisions—toward a negative, threat-based, or hopeless framework.

The Fragility of Cognitive Command: Why “Thinking Your Way Out” Often Fails

The prevailing cultural and therapeutic narrative often champions the power of the mind over emotion, suggesting that with sufficient willpower and the right cognitive tools, any feeling can be managed or overcome. This perspective places the prefrontal cortex at the apex of a clear hierarchy, capable of issuing top-down commands to regulate the more primitive emotional centers of the limbic system. While this top-down regulatory capacity exists, its effectiveness is far more fragile and context-dependent than is commonly assumed.

Cognitive reappraisal is a quintessential top-down emotion regulation strategy, defined as the act of reinterpreting the meaning of an emotionally charged situation in order to change its emotional impact. (Pioneer Publisher: The Role of Cognitive Reappraisal Strategies in Modulating Traumatic Memories) The neural circuitry underlying cognitive reappraisal involves the recruitment of executive control regions within the prefrontal cortex, which then exert a modulatory, often inhibitory, influence on the activity of emotion-generating structures like the amygdala. (ResearchGate: Amygdala-Frontal Connectivity During Emotion Regulation)

Despite the elegance of this model, its real-world application is fraught with difficulty. Laboratory research has revealed that after attempting to reappraise a negative stimulus, as many as one-third of participants report feeling worse than if they had just responded naturally. In daily life, the numbers are even more stark, with nearly half of all self-reported attempts at reappraisal being rated as “not at all successful” or only “slightly successful.” (Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience: A New Understanding of the Cognitive Reappraisal Technique) For individuals who lack skill in this area, frequent attempts at reappraisal are actually associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms.

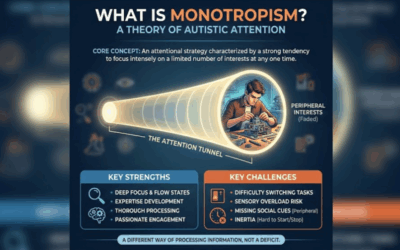

The primary culprit behind this fragility is stress. The executive functions of the prefrontal cortex, which are essential for cognitive flexibility required for reappraisal, are profoundly impaired by stress. (Frontiers in Psychology: Regulating Anger Under Stress via Cognitive Reappraisal) This creates a debilitating paradox: the more stressed and emotionally overwhelmed we become, the less capable our brains are of executing the very cognitive strategies designed to reduce that stress.

Furthermore, there appears to be an intensity threshold beyond which cognitive strategies lose their power. Studies examining pain and physical discomfort during exercise have shown that as the intensity of the physical sensation increases, attention is involuntarily drawn toward that sensory experience and away from external or cognitive distractions. (PMC: The Limits of Cognitive Reappraisal: Changing Pain Valence, but Not Persistence) While cognitive reappraisal could change the valence of pain, it did not change the pain’s intensity or a person’s ability to persist with the task. This demonstrates that when bottom-up afferent signals become sufficiently strong and salient, they can override top-down attempts to cognitively reframe them.

This dynamic can be understood as a form of neurological resource competition. The top-down regulatory functions of the prefrontal cortex are evolutionarily recent and metabolically expensive. They require significant energy and a state of relative safety to operate effectively. In contrast, the bottom-up processing of survival-relevant afferent signals by the brainstem and limbic system is evolutionarily ancient, automatic, and metabolically cheap. When the nervous system is under high stress—which is, by definition, a state of perceived threat—it enters a mode of energy conservation, prioritizing survival by allocating resources away from the “expensive” functions of the prefrontal cortex. The failure of cognitive control is therefore not a personal failing; it is a predictable and adaptive biological strategy. This is precisely why therapies that work with the subcortical brain rather than purely cognitive approaches are often more effective for deeply enmeshed emotional states.

The Predictive Brain: How the Body Locks Emotion in Place

To fully grasp why somatic feedback loops can become so powerfully entrenched and resistant to change, we must consider the brain as a “prediction engine.” The predictive coding framework proposes that the brain’s fundamental task is not to passively react to the world, but to actively predict it. (PMC: Interoceptive Predictions in the Brain) The brain constantly generates a top-down model of the world based on past experience, using this model to make predictions about what sensory input it expects to receive at any given moment. The primary job of ascending sensory pathways, in this view, is to report the difference between the brain’s prediction and the actual sensory input—the “prediction error.”

The Embodied Predictive Interoception Coding (EPIC) model proposes that the brain does not simply “feel” the body’s state passively. Instead, it actively predicts the body’s internal physiological state based on context, memory, and current needs. When there is a mismatch, an interoceptive prediction error is generated. (PMC: Active Interoceptive Inference and the Emotional Brain)

Consider the case of a chronic, maladaptive posture—for example, the collapsed, forward-flexed posture characteristic of a dorsal vagal shutdown state. This is not a fleeting state; it is a deeply habituated pattern held in the neuromuscular system and reinforced by changes in the connective tissue. This posture provides a relentless, unvarying stream of afferent information to the brain—proprioceptive signals of flexion and collapse, and visceral signals of compressed organs and shallow breathing. If the brain’s high-level model of the self includes a prediction of well-being, confidence, or safety, this constant somatic broadcast creates a massive and persistent interoceptive prediction error.

Faced with this chronic prediction error, the brain’s fundamental directive—to minimize error—kicks in. The brain has two primary ways to resolve this discrepancy: it can try to make the body conform to its prediction through efferent motor commands (active inference), or it can accept the sensory input as veridical and update its internal model to better predict that input (perceptual inference). Changing a deeply habituated physical pattern locked into the body’s tissues is extraordinarily difficult—a very high “cost” for active inference. In contrast, updating a high-level cognitive-emotional model is often the path of least resistance.

Therefore, to resolve the persistent interoceptive prediction error generated by a collapsed posture, the brain’s most efficient solution is to adopt the belief and emotion that best explains and predicts the unceasing bodily sensations. It updates its prediction from “I am safe, so I should feel calm” to “My body is in a state of collapse, therefore it makes sense that I feel hopeless, depressed, and defeated.” The negative emotion becomes enmeshed with the posture because the brain has accepted the body’s afferent signal as the “ground truth” and has constructed its subjective reality around that fact.

This reframes the entire concept of being emotionally “stuck.” From the brain’s predictive perspective, this persistent negative emotional state is not a failure of regulation; it is a resounding success. The brain has successfully minimized a chronic prediction error by achieving a state of coherence between its model and its sensory input. The state feels subjectively terrible, but to the predictive machinery of the brain, it is stable, predictable, and orderly. This explains why purely logical arguments or cognitive reframing so often fail to dislodge such states. To truly create change, the intervention must target the source of the prediction error itself: the persistent afferent signals from the body.

Intervening at the Source: The Neuroscience of Somatic Therapies

If enmeshed emotion is the brain’s stable solution to a chronic interoceptive prediction error originating in the body, then the most effective therapeutic interventions should be those that directly alter this foundational bodily signal. This is precisely the mechanism through which somatic therapies achieve their profound and often lasting effects. These modalities bypass the futile argument with the brain’s high-level cognitive centers and instead engage in a direct, tangible conversation with the body’s tissues and the autonomic nervous system.

Myofascial Release and Structural Integration: Changing the Signal at the Tissue Level

Rolfing, also known as Structural Integration, and Myofascial Release are forms of manual therapy that focus on reorganizing the body’s connective tissue, or fascia. (Dr. Ida Rolf Institute: What is Rolfing?) Fascia is a web-like matrix that surrounds, supports, and penetrates every muscle, bone, nerve, and organ in the body. Chronic postural patterns, stress, and injury can cause this fascial web to become tight, restricted, and adhered, contributing to pain and limited movement. (PMC: Structural Integration, an Alternative Method of Manual Therapy and Sensorimotor Education)

The therapeutic effects of these interventions are profoundly neurological, working primarily by altering the afferent signals sent from the periphery to the central nervous system. The fascia is richly innervated with a variety of sensory nerve endings, including mechanoreceptors that are sensitive to pressure and stretch. The slow, deep strokes characteristic of Rolfing and Myofascial Release stimulate specific types of intra-fascial mechanoreceptors (such as Ruffini and interstitial endings), which in turn send afferent signals to the central nervous system that trigger a parasympathetic response, leading to a reduction in the tone of related muscles and surrounding fascia. (PMC: A Review of the Application of Myofascial Release Therapy in the Treatment of Diseases) This is a direct, manual alteration of the proprioceptive and interoceptive information being sent to the brain.

Fascial restrictions can cause pain by compressing nerves and blood vessels, and by trapping metabolic waste products and inflammatory substances that sensitize pain receptors. By releasing these restrictions, these therapies can alleviate nerve compression and improve local circulation, thereby reducing the volume of pain and threat signals ascending to the brain. There is preliminary evidence suggesting that a course of Structural Integration can lead to measurable improvements in vagal tone, a key indicator of parasympathetic nervous system activity and overall stress resilience.

Somatic Experiencing: Completing the Survival Response

Somatic Experiencing (SE), developed by Dr. Peter Levine, is founded on the observation that animals in the wild rarely suffer from chronic trauma symptoms because they have innate physiological mechanisms for discharging the immense survival energy mobilized during life-threatening encounters. (Psychotherapy.net: Peter Levine on Trauma Healing) This discharge often takes the form of involuntary shaking, trembling, or deep, spontaneous breaths after the threat has passed.

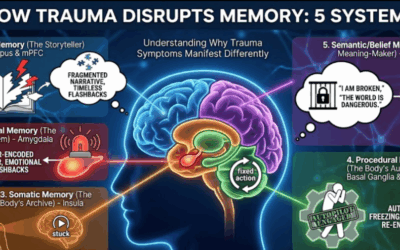

SE theory posits that human trauma often results from the interruption or incompletion of these powerful, biologically-based self-protective responses. (Somatic Experiencing International: SE 101) When this happens, the massive amount of arousal energy generated for survival does not get discharged and remains “stuck” or “bound” in the nervous system, leading to chronic autonomic dysregulation. (PMC: Somatic Experiencing: Using Interoception and Proprioception as Core Elements of Trauma Therapy) The body remains on high alert, continuously sending afferent signals of threat to the brain, even long after the actual danger is over.

The goal of SE is to facilitate the completion of these thwarted survival responses and the release of bound energy. This is not done through catharsis or re-living the traumatic event, but through a gentle, titrated process. The therapist guides the client’s attention to their internal “felt sense”—the subtle interoceptive and proprioceptive sensations occurring in the body in the present moment. By carefully alternating attention between sensations of trauma-related arousal and sensations of safety and resource (a process called “pendulation”), the client’s nervous system is given the opportunity to safely access and discharge small, manageable amounts of the stored energy. (Learn more about how SE works at Taproot)

Brainspotting: Accessing the Subcortical Through the Visual System

Brainspotting, developed by Dr. David Grand, is a powerful therapy that uses specific eye positions to access unprocessed trauma stored in the subcortical brain. (FAQs about Brainspotting) The method operates on the premise that “where you look affects how you feel.” By guiding the client’s visual focus to specific external positions (brainspots), the therapist helps access and process unresolved traumatic memories stored in subcortical brain regions.

Looking at specific eye positions stimulates the brain activity that underlies traumatic experiences, accessing subcortical brain structures including the amygdala, hippocampus, and brain stem. (The Neuroscience of Brainspotting) Focusing the eyes on the brainspot appears to activate and release traumatic memories from these lower brain networks without engaging the conscious neocortex, allowing implicit subcortical memories to process rapidly. (How Brainspotting Works in the Brain)

Unlike purely cognitive approaches, Brainspotting is almost purely somatic and subcortical. It operates on the “felt sense” in the body. While insights may arise, the goal is not to create a new belief, but to release the stored activation in the nervous system. (Learn the differences between Brainspotting and EMDR) Many clients who feel “stuck in their heads” find Brainspotting allows them to finally drop into their bodies and process what talk therapy could not reach.

EMDR: Bilateral Stimulation and Memory Reconsolidation

EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing) is an evidence-based psychotherapy that uses bilateral stimulation to help the brain reprocess traumatic memories that have become “stuck” in the nervous system. One of the core principles of EMDR is the concept of memory reconsolidation—when a traumatic memory is activated, it becomes temporarily malleable and can be modified. The bilateral stimulation is believed to facilitate the adaptive processing of traumatic memories, leading to their reconsolidation in a less distressing and more integrated form.

Neurobiological studies have shown that bilateral stimulation can influence the amygdala, dampening its response to traumatic memories and facilitating their reconsolidation in a less emotionally charged state. This process aligns with the principles of fear extinction and memory reconsolidation, both of which play a crucial role in trauma resolution. EMDR has been demonstrated effective across diverse clinical populations, with meta-analyses showing moderate-to-large effect sizes for long-term PTSD outcomes.

Emotional Transformation Therapy: Harnessing Light and Color

Emotional Transformation Therapy (ETT), developed by Dr. Steven Vazquez, is a cutting-edge approach that combines somatic and cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and brain-based medicine to create unprecedentedly fast emotional healing. (How Color and Light Heal Trauma) ETT’s utilization of specific light frequencies and eye movements engages the subcortical, mid, and neocortical parts of the brain to synchronize intellectual and emotional thought.

Unlike traditional talk therapy, ETT directly interacts with neural networks, allowing for efficient access to deep-seated emotional states and traumatic memories. By strategically stimulating these networks through the precise application of color, light, and eye movements, ETT promotes rapid reprocessing and integration of traumatic experiences. (From Skepticism to Science: How ETT is Revolutionizing Treatment) The power of ETT lies in its ability to bypass the conscious mind’s defenses and directly access the emotional brain, where traumatic memories and experiences are stored.

Re-contextualizing “Body Memory”: From Pseudoscience to Neuroscience

The effectiveness of somatic therapies often leads to discussions of “body memory,” a concept that can be both powerful and problematic. It is crucial to address the valid skepticism surrounding the literal interpretation of this term. There is currently no known biological mechanism for declarative memories to be stored in bodily tissues outside of the brain. Body Memory, or the notion that muscles or fascia can literally “hold” a memory of an event is not supported by neuroscience.

However, the phenomenon that “body memory” attempts to describe is very real and can be re-contextualized through well-established neurobiological processes. Chronic postures and patterns of muscular tension are forms of implicit or procedural memory—memories of “how to do” something, stored not in the muscles themselves, but in the subcortical brain circuits like the cerebellum and basal ganglia that control them. A slumped posture is a learned, habituated motor pattern, a procedural memory for how to hold the body in a state of defeat.

This motor pattern is linked with autonomic conditioning, where a particular posture can become a conditioned stimulus that automatically triggers a full-blown survival response based on past experiences. The body’s tissues then physically adapt to these conditioned patterns; fascia, in response to chronic tension, will lay down additional collagen fibers, becoming stiffer and less pliable. This physically altered tissue becomes a source of persistent, pathological afferent feedback that constantly reinforces the brain’s original threat-based model.

In this light, somatic therapies are not releasing a literal “memory” from the tissue. They are intervening at a critical point in this self-sustaining loop. By manually changing the tissue’s properties or by facilitating the discharge of conditioned autonomic arousal, they introduce novel afferent information that interrupts the pattern, providing the opportunity for neuroplastic change.

The Power of the Upward Loop: A Synthesis

The fundamental argument for the power of somatic psychology lies in the asymmetrical nature of the body-brain dialogue. The ascending, or afferent, feedback loops that carry information from the body to the brain are often more powerful and persistent than the descending, or efferent, loops that carry cognitive commands from the brain to the body. This neurobiological reality explains why directly changing the body’s physical state can be a profoundly effective method for regulating emotion.

Posture is not merely a biomechanical arrangement but a continuous neurological broadcast of one’s perceived state of safety or threat. A collapsed, slumped, or defensive posture sends a relentless stream of afferent signals to key emotional processing centers in the brainstem, limbic system, and insular cortex. The brain receives this raw data and interprets it as the primary evidence for an emotional state. A body broadcasting signals of collapse will lead the brain to generate feelings of hopelessness and defeat, just as a body broadcasting signals of tension and bracing will lead to feelings of anxiety and fear. This bottom-up generation of emotion can happen automatically and precede any conscious, top-down cognitive appraisal.

This is why purely cognitive strategies often fail in the face of enmeshed emotion. An attempt to “think” one’s way out of anxiety is an attempt to use the weaker efferent pathway to override a stronger, continuous afferent broadcast. The brain struggles to maintain the cognitive belief “I am safe” when the body’s perceptual reality is broadcasting “I am in danger.” The persistent somatic signal creates a powerful feedback loop that reinforces the negative emotional state, making it highly resistant to cognitive intervention.

Somatic and brain-based therapies offer a powerful alternative by intervening at the source of the signal. Instead of arguing with the brain’s emotional interpretation, they change the physical data the brain is receiving. By guiding an individual to consciously shift their posture from a collapsed or constricted state to one that is upright, open, and balanced—or by releasing fascial restrictions, completing survival responses, or accessing subcortical processing through eye positions—these therapies help alter the afferent broadcast. An upright, released body sends new signals of capability, stability, and safety to the brain. This new information interrupts the old, negative feedback loop and initiates a new, positive one. The brain receives the message of physical safety and, in response, can more easily generate feelings of calm, confidence, and ease.

Implications for Therapy and Personal Healing

The evidence synthesized in this article constructs a compelling neurobiological argument for the primacy of the body in the generation and persistence of emotional states. The implications are profound and far-reaching.

A Call for Integrated Therapies: This model argues strongly against a false dichotomy between “mind-based” and “body-based” therapies. Effective treatment for many chronic emotional conditions, particularly those rooted in trauma and chronic stress, likely requires an integrated approach that addresses both top-down cognitive patterns and bottom-up somatic drivers. Modalities like Somatic Experiencing, Brainspotting, EMDR, Emotional Transformation Therapy, and myofascial release should not be seen as alternative or complementary, but as essential tools for intervening at the physiological root of emotional distress.

Empowerment Through Embodiment: Understanding these principles empowers individuals with a new lever for self-regulation. It shifts the focus from a frustrating and often futile internal battle of “mind over matter” to a more compassionate and effective practice of attending to the body. Simple, accessible practices like mindful posture correction, conscious breathing techniques that stimulate vagal tone, and interoceptive awareness exercises can become primary tools for managing emotional well-being.

A Non-Pathologizing Perspective: This framework offers a deeply compassionate and non-pathologizing view of emotional suffering. Being “stuck” in an emotion like depression or anxiety is not a sign of a character flaw, a weak will, or a “broken” brain. Instead, it can be understood as a predictable, and in some ways intelligent, adaptation of the nervous system to a persistent internal signal of threat or dysregulation. Healing, therefore, is not about “fixing” a broken part, but about providing the nervous system with new experiences of safety that allow it to emerge from a chronic survival state.

The core message is one of hope and agency. The body is not just the site of our pain; it is the most direct and powerful gateway to our healing. By learning to listen to and work with our physiology, we can actively shape our emotional reality from the ground up. This shifts us from a position of passive suffering to one of active participation in our own well-being, providing a transformative and actionable path that lies at the heart of truly effective psychotherapy.

If you are struggling with trauma, anxiety, depression, or persistent emotional dysregulation that hasn’t responded to traditional talk therapy, we encourage you to explore the brain-based and somatic approaches available at Taproot Therapy Collective. Our specialized therapists are trained in Brainspotting, Somatic Experiencing, EMDR, Emotional Transformation Therapy, and other modalities designed to work with the body-brain connection to facilitate deep, lasting healing.

0 Comments