You remember what you had for breakfast yesterday, but you can’t recall years of your childhood. You have no visual memory of the assault, yet your body freezes when someone stands too close. You know the car accident happened, but when you try to tell the story, it comes out fragmented and out of order.

These aren’t signs that something is wrong with your memory. They’re signs that your memory is working exactly as it was designed to work under extreme stress—and understanding this can change how you approach healing.

But here’s what most articles on trauma won’t tell you: understanding the neuroscience is only half the equation. The other half involves a question the mental health field has been fighting about for decades—whether trauma therapy is fundamentally an art or a science, and what we lose when we try to reduce healing to a manual.

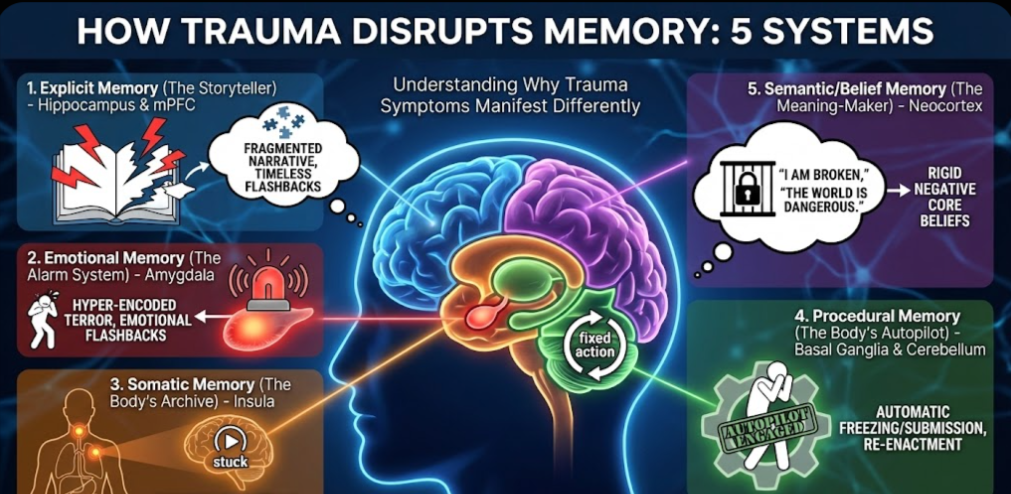

Your Brain Has Multiple Memory Systems (And Trauma Affects Each One Differently)

Most people think of memory as a single thing—like a video recording you can play back. But your brain actually runs several distinct memory systems simultaneously, each with its own neural architecture, its own rules, and its own way of breaking down under stress. Research published in Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience confirms that these systems can be differentially affected by traumatic stress.

This isn’t just academic knowledge. It has profound implications for treatment. Because if trauma lives in different memory systems, then different therapeutic approaches are needed to reach it—and some of those approaches resist the standardization that modern healthcare demands.

Understanding which system holds your trauma explains why you experience the specific symptoms you do—and why the treatment that works for one person may not work for another.

System 1: Explicit Memory (The Storyteller)

What It Does

Explicit memory is what most people mean when they say “memory.” It’s conscious, narrative, and autobiographical. It allows you to recall facts (semantic memory) and events (episodic memory). It answers questions like: What happened? When did it happen? Where was I? According to The Decision Lab’s neuroscience reference, this system is fundamental to how we construct our life stories.

This system depends heavily on the hippocampus—often called the brain’s “librarian”—and its connections to the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). The hippocampus timestamps events, placing them in sequence: “This happened then, there, and is now over.”

How Trauma Disrupts It

Here’s the cruel irony: the hippocampus is exquisitely sensitive to stress hormones. It’s dense with glucocorticoid receptors, which means that during extreme stress, the very system you need to create a coherent memory gets taken offline. Research published in PMC examining PTSD’s neurobiological impact demonstrates how cortisol floods during trauma effectively inhibit hippocampal functioning.

This isn’t a malfunction. It’s an evolutionary feature. When you’re facing a life threat, your brain doesn’t waste metabolic energy on complex cognitive mapping. It prioritizes immediate survival over documentation.

The result: the traumatic event never gets properly “filed.” It doesn’t receive a timestamp. It doesn’t get tagged as “past.” A comprehensive review in Psychopharmacology details how this declarative memory impairment manifests in PTSD patients.

What This Looks Like Clinically

- Fragmented narrative: You can’t tell the story in order. Pieces are missing. The timeline doesn’t make sense.

- Visual/auditory flashbacks: Because the event wasn’t stamped as “past,” your brain treats it as “present.” You don’t remember the trauma—you re-live it.

- Gaps in autobiographical memory: Entire periods of your life may be inaccessible, especially if trauma was chronic during childhood.

- Confusion about what’s real: Without hippocampal context, you may struggle to distinguish memory from imagination, or past from present.

The Neuroscience of the “Timeless” Flashback

A flashback isn’t just an intense memory. It’s what happens when your brain lacks the neural machinery to recognize that the event is over. The hippocampus normally tells the prefrontal cortex: “This is a memory, not current reality. You’re safe on your couch.” But if the hippocampus was offline during encoding, that safety signal never gets sent. Cambridge University Press research on trauma and memory explains this mechanism in detail.

The connection between the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex—which normally allows you to regulate fear by placing it in context—is severed. Research on hippocampal connectivity changes after traumatic memory reactivation confirms these disrupted neural pathways. The result is unmediated terror that feels eternal because it has no temporal boundaries.

System 2: Emotional Memory (The Alarm System)

What It Does

While the hippocampus collapses under stress, the amygdala—the brain’s threat detector—goes into overdrive. The amygdala encodes the emotional significance of experiences. It creates rapid associations between sensory cues and survival responses.

Unlike the hippocampus, the amygdala is less susceptible to cortisol suppression. In fact, stress hormones enhance amygdala encoding. Research published in Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience details the neural circuits and molecular mechanisms underlying this fear dysregulation in PTSD. This creates a paradox: the narrative of the trauma is forgotten, but the emotional terror is hyper-encoded.

How Trauma Disrupts It

The amygdala creates “hot” associations between sensory triggers and life-threat responses. The color red. The smell of alcohol. A particular tone of voice. These become wired directly to the survival alarm, bypassing conscious thought.

This is adaptive in the short term—it keeps you ready to respond to genuine threats. But the amygdala doesn’t do nuance. It can’t distinguish between the original threat and something that merely resembles it. A study in MDPI Brain Sciences examines how trauma duration impacts the volumetric and microstructural parameters of the amygdala.

What This Looks Like Clinically

- Emotional flashbacks: Sudden, overwhelming waves of terror, shame, despair, or rage—without any visual or narrative component. You feel exactly as you did during the trauma but have no idea why. Here Counseling’s clinical guide provides detailed descriptions of this phenomenon.

- Hypervigilance: Your threat detection system is calibrated for danger. You scan rooms for exits. You startle at sounds others don’t notice.

- Trigger responses that don’t make sense: You panic when you smell a certain cologne. You feel overwhelming shame when someone uses a particular phrase. The reaction seems “crazy” because you can’t access the original context.

- Alexithymia: Difficulty putting emotions into words. The amygdala is screaming, but the signal isn’t reaching the language centers.

The Emotional Flashback Explained

An emotional flashback is what happens when the amygdala fires without the hippocampus providing context. You experience the exact feeling state of the original trauma—the despair of abandonment, the terror of violence, the shame of humiliation—but your conscious mind has no access to the “why.”

This is why emotional flashbacks are so disorienting. You feel like you’re dying, but you’re sitting in a safe coffee shop. You feel like a worthless child, but you’re a successful adult. The feeling is real; the context is missing. Research on implicit memory in trauma-related disorders explains how these non-declarative systems operate below conscious awareness.

System 3: Somatic Memory (The Body’s Archive)

What It Does

The insular cortex (insula) is the brain’s center for interoception—sensing the internal state of your body. It maps visceral sensations: heartbeat, gut activity, temperature, pain, pressure. It creates your felt sense of being embodied. A comprehensive review in PMC on interoception and mental health details this critical brain-body connection.

Trauma often involves overwhelming physical sensations—pain, suffocation, nausea, penetration. The insula records these visceral states with extraordinary fidelity.

How Trauma Disrupts It

The insula doesn’t just record what happened to your body. Under trauma, it creates a predictive model: “This is what my body feels like when I’m in danger.” The brain then uses this model to predict future threat. This aligns with Karl Friston’s Free Energy Principle, which frames the brain as a prediction machine constantly modeling expected states.

The problem is that the model can become “stuck.” Your brain continues predicting the traumatized body state—pain, compression, nausea—even when your actual body is safe and unharmed. Research in PMC on active inference and interoceptive psychopathology explores this mechanism in detail.

What This Looks Like Clinically

- Somatic flashbacks: You feel the hands of the perpetrator on your skin. You experience the sensation of strangulation. You smell smoke that isn’t there. These aren’t memories—they’re the brain simulating the trauma in real-time.

- Chronic unexplained pain: Pelvic pain, throat tightness (globus sensation), chest pressure, or burning sensations that have no structural cause.

- Dissociation from the body: Because the body became a site of pain, the brain may withdraw attention from it entirely. You feel disconnected from physical sensations, as if your body belongs to someone else. Our article on the neuroscience of dissociation explores this protective mechanism.

- Interoceptive confusion: Difficulty distinguishing hunger from anxiety, fatigue from depression, physical arousal from fear.

The Interoceptive Hallucination

A somatic flashback is technically an interoceptive hallucination. The brain is predicting a body state with such high confidence that it generates the sensation even when the physical cause is absent. Research published in MIT Press on affect and active inference explores how the brain generates these visceral predictions.

A survivor of strangulation may experience chronic throat tightness not because anything is wrong with their throat, but because their insula is predicting compression. The brain is simulating the trauma to be ready for it—a preparation that became permanent.

System 4: Procedural Memory (The Body’s Autopilot)

What It Does

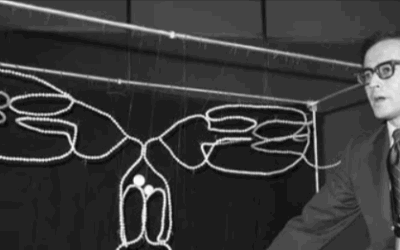

Procedural memory lives in the basal ganglia (specifically the striatum) and cerebellum. It encodes “how to” rather than “what.” It’s the memory of riding a bike, typing without looking, or playing piano—motor sequences that become automatic. Research in the Journal of Neuroscience confirms the hippocampus also plays a role in maintaining procedural motor memory.

Critically, this system also encodes defensive motor patterns: how to freeze, flee, fight, or submit. These are “fixed action patterns” that fire automatically when triggered.

How Trauma Disrupts It

The striatum learns through dopamine-mediated reinforcement. If a child learns that freezing reduces the severity of abuse, the striatum encodes “freeze” as the optimal survival policy. If submission prevents escalation, submission becomes the default. A study in PMC on active inference and psychological trauma frames this as maladaptive explore-exploit dynamics.

These aren’t conscious choices. They’re procedural habits that bypass conscious control entirely. The “decision” to freeze happens before the prefrontal cortex even knows what’s occurring.

What This Looks Like Clinically

- Automatic freezing: You physically cannot move or speak during confrontation, even when you know you’re safe. Your mind goes blank. Your body locks up.

- Compulsive submission (fawning): You automatically agree, placate, or comply—even when you don’t want to. The “fawn” response fires before you can stop it.

- Defensive postures: Chronic tension patterns, habitual flinching, shoulders hunched in protection.

- Re-enactment patterns: You find yourself in relationships or situations that mirror the original trauma. The striatum guides you toward familiar states—even painful ones—because they’re predictable.

The Survival Habit That Became a Prison

A 30-year-old executive who freezes when a colleague raises their voice isn’t choosing to freeze. Her striatum learned decades ago that freezing prevents escalation. That motor program saved her life as a child. Now it activates automatically in any situation her amygdala codes as similar—even a work meeting.

She’s conscious of her inability to respond (high frustration) but unconscious of the motor program’s origin. Her “self” has been temporarily paralyzed by her “survival machine.”

System 5: Semantic/Belief Memory (The Meaning-Maker)

What It Does

The neocortex—especially the temporal lobes—stores semantic knowledge: general facts about the world, abstract concepts, and beliefs. This includes beliefs about yourself, others, and reality.

How Trauma Disrupts It

Trauma doesn’t just change what you remember. It changes what you believe. The brain creates generalized conclusions from traumatic data: “The world is dangerous.” “I am fundamentally damaged.” “People will always abandon me.”

These beliefs become “stuck priors”—rigid predictions that resist updating even when contradicted by evidence. Research on epistemic trust and psychopathology shows how trauma can create “firewalls” against new information. The brain trusts these traumatic conclusions so deeply that it ignores or distorts information that conflicts with them.

What This Looks Like Clinically

- Negative core beliefs: “I am worthless.” “I am permanently broken.” “It was my fault.” “No one can be trusted.”

- Overgeneralization: One abusive man becomes “all men are dangerous.” One abandonment becomes “everyone leaves eventually.”

- Epistemic mistrust: Inability to take in positive feedback or validation. The belief system has a “firewall” against information that contradicts it. Research on resolving epistemic mistrust in psychotherapy addresses this treatment challenge.

- “Yes, but” thinking: Any evidence of safety, worth, or love gets explained away to maintain the traumatic worldview.

The Transgenerational Dimension: Trauma Before Memory

The neuroscience becomes even more complex when we consider that trauma can be transmitted before conscious memory even exists.

The Dutch Hunger Winter study demonstrates how deeply trauma embeds in the body. Children whose mothers experienced famine during early gestation in 1944-1945, though born into first-world conditions and never knowing hunger themselves, showed increased rates of obesity and metabolic dysfunction decades later. This physiological response activated in utero, preparing them for a world of scarcity that never materialized.

This isn’t intellectual knowledge learned through observation. It’s a body-brain response programmed before birth through epigenetic mechanisms. The implications are staggering: some trauma responses exist in people who never consciously experienced the original threat.

This is why simply thinking about trauma or analyzing it doesn’t release these deep physiological patterns. The trauma exists in systems that predate language, consciousness, and autobiographical memory.

The Treatment Dilemma: When Different Memories Need Different Languages

Understanding which memory system holds your trauma changes everything about how you approach healing. Different systems require different interventions because they speak different languages. Research in Frontiers in Psychology on psychoanalytic psychotherapies and the free energy principle supports this targeted approach.

But here’s where the mental health field runs into a fundamental tension—one that has profound implications for how therapy is practiced, taught, funded, and regulated.

You Can’t Talk a Somatic Memory Out of Existence

The insula doesn’t understand English. If your trauma lives in your body—as chronic pain, as phantom sensations, as a feeling of being unsafe in your own skin—talk therapy alone won’t reach it.

Somatic approaches (Somatic Experiencing, sensorimotor psychotherapy) work by helping the insula update its predictions. By focusing on the “felt sense” in a safe environment, you generate new data: “I felt the fear, but I didn’t die.” This reduces the brain’s confidence in its danger predictions.

You Can’t Think Your Way Out of a Procedural Memory

The striatum doesn’t respond to insight. Knowing why you freeze doesn’t stop you from freezing. Procedural memories require procedural interventions—movement, action, embodiment.

Movement-based therapies, yoga, martial arts, and drama therapy work by writing new motor programs. “Power posing” or defensive movements (pushing away) in safe contexts teach the striatum that action—not just freezing—is a viable policy.

Narrative Integration Requires the Hippocampus to Come Back Online

For fragmented flashbacks, the goal is timestamping. EMDR and Narrative Exposure Therapy work by helping the hippocampus place the event in the past. The bilateral stimulation in EMDR taxes working memory, lowering the intensity of the flashback while the therapist guides narrative construction.

This may involve memory reconsolidation—the actual unlocking and rewriting of the synaptic encoding. Research from the Wounded Healers Institute on memory reconsolidation explains this mechanism. By activating the memory while simultaneously experiencing safety, the brain is forced to update its predictions.

Emotional Flashbacks Need Safety Signals

The amygdala learns through experience, not logic. You can’t convince it you’re safe; you have to show it, repeatedly, through lived experience of non-harm. Research published in Frontiers on touch and verbal communication in therapy explores how the therapeutic relationship provides these safety signals.

This is why the therapeutic relationship matters so much for trauma work. The amygdala needs to experience that another human can be present during distress without causing more harm. This builds the neural pathways for co-regulation that may never have developed.

The Art vs. Science Debate: What Gets Lost in Manualization

Here’s where the neuroscience collides with healthcare economics and professional politics.

The mental health field has been fighting about this for decades: Is therapy fundamentally an art—requiring intuition, attunement, and creative responsiveness that can’t be reduced to protocols? Or is it a science—best practiced through standardized, evidence-based procedures that can be taught, measured, and replicated?

The answer, of course, is both. But the field has been pushed hard toward the “science” pole by forces that have little to do with what actually helps traumatized people heal.

The Rise of Manualized Therapy

Starting in the 1980s, managed care transformed mental health treatment. Insurance companies wanted therapies that were:

- Standardized: The same treatment delivered the same way by different therapists

- Measurable: Clear outcomes that could be tracked on symptom scales

- Brief: Limited to 5-20 sessions

- Replicable: Teachable through manuals and training protocols

This created enormous pressure to develop “manualized” therapies—treatments where each session follows a prescribed structure, where interventions are specified in advance, and where therapist discretion is minimized. Research cited in JAMA Internal Medicine shows that over 80% of psychotherapists now don’t accept public insurance, highlighting how these economic pressures have shaped the field.

Everything pushed forward had “brief” or “solution-driven” or “time-limited” attached. This was mainly driven by research funded by entities wanting people better faster—but it ended up creating a lot of band-aids that didn’t get to the root of the issue.

The Genuine Benefits of Manualization

To be fair, manualized approaches solved real problems:

Quality control: Before standardization, “therapy” could mean almost anything. Some practitioners were helping; others were causing harm. Manuals created accountability.

Training efficiency: New therapists could learn proven techniques rather than reinventing the wheel or relying solely on apprenticeship with potentially problematic mentors.

Research validity: You can’t study “therapy” as a vague category. Manualized treatments allowed researchers to know what was actually being delivered.

Access: Standardized treatments can be disseminated more widely than approaches requiring years of mentorship with master clinicians.

CBT in particular emerged from this movement and has demonstrated genuine efficacy for specific conditions—depression, anxiety disorders, specific phobias. For some presentations, manualized treatment works beautifully.

What Gets Lost: The Limits of Protocol

But here’s what the manualization movement missed: trauma doesn’t live in the parts of the brain that respond to protocol.

You can understand exactly why you smoke cigarettes, trace it back to early attachment patterns, discuss what your mother did, spend fifty years in analysis gaining profound insights into your neurosis—and still smoke cigarettes. You can understand everything intellectually without touching the actual problem, because the problem doesn’t live in the prefrontal cortex. It lives in the deep emotional system: how much energy you respond to life with, your reaction to being confronted, your reaction to having an emotional need. All of that happens in the body before it colors cognition.

Simply thinking about it and analyzing it doesn’t get that emotional defensive response out.

The same limitation applies to manualized trauma treatments. A therapist following a session-by-session protocol may miss the moment when the client’s body is ready to complete an interrupted defensive response. They may push cognitive restructuring when the client needs to sit in silence with a somatic sensation. They may move to the next prescribed intervention when the healing is happening right now, in the pause, in the space between words.

What Can’t Be Taught: The Problem of Implicit Clinical Knowledge

Some of the most effective trauma interventions resist manualization entirely because they depend on capacities that can’t be reduced to steps.

David Grand, founder of Brainspotting, repeatedly tells trainees to “turn off your brilliance.” The approach works precisely by not interpreting, not analyzing, not directing. The therapist follows the client’s process, trusting that the deep brain is intelligent and wants to heal. Anything the therapist says gets in the way. Anything suggested won’t be as smart as what the patient’s deep brain can generate.

How do you manualize “turn off your brilliance”? How do you train someone to trust a process they can’t see or predict? How do you standardize the intuition that tells a skilled somatic therapist this is the moment to stay silent, this is the moment to offer a word, this is the moment to track the client’s eyes?

Peter Levine’s Somatic Experiencing faces similar challenges. The therapist must track subtle shifts in the client’s nervous system—changes in skin color, breathing patterns, micro-movements—and respond in real-time. This requires a kind of embodied attunement that develops over years of practice and can’t be transmitted through a manual.

Richard Schwartz’s Internal Family Systems explicitly warns against therapist interpretation. You’re not supposed to say “I think there’s a part of you that’s afraid of being judged and that part is creating another piece that judges everybody.” You’re supposed to help the client directly experience their parts—which requires following their process rather than imposing a structure.

Fritz Perls, founder of Gestalt therapy, would have someone come in saying they’re depressed, and he’d say “Yeah, feel the depression. Go there, get as depressed as you can. Where do you feel that in your body? Just go into it.” Through pushing them into that very deep subcortical experience, they start to realize they can survive that area and begin to heal. The therapist isn’t analyzing at all—they’re creating conditions for experience.

These approaches work precisely because they don’t follow a script. They respond to what’s emerging in the moment. They trust the client’s process over the therapist’s agenda. They access implicit memory systems through implicit relational processes that resist explicit codification.

The Neuroscience of Why Some Approaches Resist Manualization

This isn’t mysticism. It’s neuroscience.

Different brain networks correspond to different therapeutic approaches:

- Executive Control Network: Goal-directed problem-solving. This is what manualized CBT targets—conscious thought restructuring, behavioral planning, cognitive reappraisal. Research by Cole et al. (2013) in Neuron identified this network’s role in adaptive task control.

- Default Mode Network: Self-reflection, introspection, meaning-making. This is what psychodynamic approaches engage—narrative construction, autobiographical memory, reflective function. Raichle et al. (2001) discovered this network in PNAS.

- Salience Network: Interoceptive awareness, determining what deserves attention. This is what somatic approaches target—felt sense, body-based processing, nervous system regulation. Uddin (2015) characterized this network in Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

The Executive Control Network responds well to explicit instruction and structured protocols. You can teach someone cognitive restructuring through a manual.

But the Salience Network operates largely below conscious awareness. Accessing it requires implicit processes—the therapist’s nervous system co-regulating with the client’s, nonverbal attunement, moment-to-moment responsiveness to shifts in physiological state. These processes are learned through experience and mentorship, not manuals.

Research by Fox et al. (2005) in the Journal of Neuroscience demonstrated an anti-correlation between DMN and ECN activity. This suggests that different therapeutic approaches aren’t just targeting different symptoms—they’re activating fundamentally different brain systems that may actually inhibit each other.

The Dangers of Forcing Manualization

When we force depth-oriented and somatic approaches into manualized formats, several things can go wrong:

Premature intervention: The protocol says to move to phase 3, but the client’s nervous system isn’t ready. Pushing forward can overwhelm rather than heal.

Missed opportunities: The client’s body is doing exactly what it needs to do to process trauma, but the therapist redirects to the next prescribed step.

Therapist anxiety: Clinicians trained primarily in manualized approaches may feel lost when protocol doesn’t apply—and their anxiety transmits to clients whose nervous systems are exquisitely attuned to threat cues.

False precision: The manual creates an illusion of control over an inherently unpredictable process. Trauma healing isn’t linear, doesn’t follow timelines, and can’t be scheduled into twelve sessions.

Retraumatization: Ketamine infusions with no guide, no psychoeducation, no knowledge about trauma can really damage people because you’re turning on all this decompensated material without giving them tools to deal with it or integrate it. The same applies to any approach that opens deep material without adequate attunement and containment.

A Map of Your Symptoms to Your Memory Systems

Use this as a guide to understand where your trauma might be stored:

If You Experience Visual/Narrative Flashbacks:

System involved: Explicit (hippocampus)

What’s happening: The event wasn’t timestamped as “past”

Helpful approaches: EMDR, Narrative Exposure Therapy, timeline work

Manualization status: These approaches can be partially manualized, though skilled practice still requires clinical judgment about pacing and readiness.

If You Experience Emotional Flashbacks (Terror/Shame Without Content):

System involved: Emotional (amygdala)

What’s happening: Threat associations firing without context

Helpful approaches: Grounding, co-regulation, gradual exposure with safety

Manualization status: Grounding techniques can be taught; co-regulation requires embodied attunement that develops over time.

If You Experience Somatic Flashbacks (Body Sensations, Phantom Pain):

System involved: Somatic (insula)

What’s happening: The brain is predicting a traumatized body state

Helpful approaches: Somatic Experiencing, Brainspotting, body-based therapies

Manualization status: These approaches resist manualization. Effective practice requires implicit attunement skills that develop through extensive supervised experience.

If You Experience Automatic Freezing/Submission:

System involved: Procedural (striatum)

What’s happening: Survival motor programs firing automatically

Helpful approaches: Movement therapies, completing defensive responses, embodiment work

Manualization status: Movement sequences can be taught; recognizing the moment of readiness for defensive completion requires clinical intuition.

If You Experience Rigid Negative Beliefs:

System involved: Semantic (neocortex)

What’s happening: Generalized conclusions became “stuck”

Helpful approaches: Cognitive processing, schema therapy, evidence-gathering

Manualization status: These approaches manualize well and have strong research support for this specific symptom cluster.

The Path Forward: Integration Over Ideology

True recovery requires speaking to each memory system in its own language:

- To the cortex: Narrative, meaning-making, cognitive restructuring

- To the amygdala: Safety, co-regulation, graduated exposure

- To the insula: Breath, interoceptive awareness, somatic tracking

- To the striatum: Movement, action, completing defensive responses

- To the hippocampus: Timeline, context, “then vs. now” discrimination

This is why effective trauma therapy is multimodal. It’s why you might need EMDR and somatic work and relational repair. Different symptoms point to different systems, and each system needs its own key.

The future of trauma therapy lies not in choosing sides in the art vs. science debate, but in recognizing that different aspects of healing require different approaches—some of which can be standardized and some of which can’t.

We need manualized approaches for what manuals can reach. And we need clinicians with the depth of training, the embodied attunement, and the clinical wisdom to work with what manuals can’t touch.

What This Means for Finding the Right Treatment

If you’re seeking trauma therapy, consider:

Where does your trauma seem to live? If it’s primarily in thoughts and beliefs, evidence-based cognitive approaches may help. If it’s in your body, your automatic reactions, your felt sense—you may need approaches that resist easy manualization.

What has your experience been with structured approaches? If protocol-based treatments have helped, that’s valuable information. If you’ve done CBT or manualized trauma treatments without the problem budging, the issue may be that the trauma lives in systems those approaches don’t reach.

How does the therapist practice? Do they follow a rigid protocol, or do they respond to what’s emerging in the moment? Do they track your body as well as your words? Do they seem comfortable with silence, with not-knowing, with following your process rather than directing it?

What’s their training background? Deep somatic and experiential work requires extensive supervised practice—not just weekend workshops. Ask about their training hours, their ongoing supervision, their own therapeutic work.

Working With Trauma-Informed Specialists

At Taproot Therapy Collective, we integrate multiple approaches to trauma because we understand that different memory systems require different interventions. Our clinicians are trained in Brainspotting, EMDR, somatic approaches, IFS, and depth psychology—and more importantly, they’ve developed the clinical intuition to know when to apply what.

We don’t believe in one-size-fits-all trauma treatment. We don’t believe the deepest healing can be reduced to a manual. And we don’t believe you should have to choose between evidence-based practice and the kind of attuned, responsive therapy that reaches the places where trauma actually lives.

If you’ve been frustrated by therapy that stayed on the surface, or overwhelmed by therapy that went too deep too fast, or confused about why some approaches help and others don’t—we can help you understand which memory systems are involved and how to approach healing in a way that actually reaches them.

About This Article

This guide was written by Joel Blackstock, LICSW-S, Clinical Director of Taproot Therapy Collective, a Birmingham-based psychotherapy practice specializing in complex trauma, somatic approaches, and integrative treatment. We believe that understanding both the neuroscience of trauma and the limitations of standardized treatment empowers survivors to find the healing they actually need.

Key Sources:

van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. Penguin Books.

Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

Lanius, R. et al. (2010). The Impact of Early Life Trauma on Health and Disease. Cambridge University Press.

Solms, M. (2021). The Hidden Spring: A Journey to the Source of Consciousness. W.W. Norton.

Dehaene, S. (2014). Consciousness and the Brain. Viking.

Raymaker, D. et al. (2020). Autistic Burnout. Autism in Adulthood.

Cole, M.W. et al. (2013). Multi-task connectivity reveals flexible hubs for adaptive task control. Neuron.

Uddin, L.Q. (2015). Salience processing and insular cortical function and dysfunction. Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

Grand, D. (2013). Brainspotting: The Revolutionary New Therapy for Rapid and Effective Change. Sounds True.

Levine, P. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. North Atlantic Books.

Last updated: January 2026

0 Comments