On the hidden physics governing digital reality, the economics of visibility, and why a psychotherapy blog in Birmingham had to learn the language of machines to fund human healing.

There is a moment in Adam Curtis’s documentary HyperNormalisation when he describes how governments, financiers, and technological utopians gave up on trying to shape the complex “real world” and instead established a simpler “fake world” for the benefit of those who needed stability. The term comes from the Soviet Union, where everyone knew the system was failing but no one could imagine an alternative, so they accepted a manufactured version of reality as normal. Curtis calls this “perception management”: the deliberate simplification of complexity to maintain control.

I think about this documentary often when I consider what has happened to the internet.

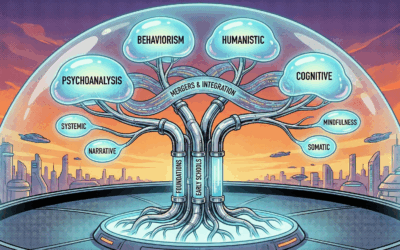

I never wanted to know anything about SEO. I am a trauma therapist in Birmingham, Alabama. I founded a collective to bring new healing modalities to my area. Somatic Experiencing. Brainspotting. EMDR. Approaches that work with the body, not just the mind. Approaches that the mainstream medical establishment was slow to recognize. I needed to fund this work, and in 2025 that means you need a website that people can find.

Now I have one of the top performing websites in my niche. I achieved this not by being the best therapist or having the most profound insights, but by learning to speak a language that was never designed for humans. I learned to write for an algorithm. And in learning this, I came to understand something disturbing: the web pages you see have been decided on before you ever got to make a decision yourself.

The Medium Is the Algorithm

Marshall McLuhan wrote in 1964 that “the medium is the message.” He meant that the structural properties of a communication medium, whether print or television or radio, exert a greater influence on human society than the actual content transmitted through them. The medium shapes how we think, what we perceive, what questions we are capable of asking.

McLuhan died in 1980. He never saw the internet as we know it. But his insight has never been more relevant. Because in the contemporary internet, the “medium” is not merely the browser or the fiber-optic cable. The medium is the Algorithm. Specifically, the Google Search algorithm. Its constraints, preferences, and biases have become the invisible physics governing digital reality.

For a psychotherapy collective, this is not theoretical. It is economic. To be visible is to exist. To be invisible is to fail. And visibility is a function of conformity to rules written by engineers in Mountain View who have never met a trauma patient, who do not know what a Brainspot is, who could not care less about the nuances of Polyvagal Theory. Their concern is indexing, retrieval, and advertising revenue.

The “message” of my blog post about somatic healing is no longer just the therapeutic insight it contains. The message is also its headers, its keyword density, its schema markup, and its domain authority. When I change my tone from empathetic to authoritative to satisfy a “trust signal,” or restructure a nuanced exploration of trauma into a listicle to capture a “Featured Snippet,” the medium has successfully rewritten the message.

Why Google Won

To understand why the algorithm dictates what we see, we must understand the chaos it solved.

In the mid-1990s, the web was organized primarily through human curation. Yahoo! began not as a search engine but as a hierarchical directory. If you wanted to find a therapist, you would navigate through Health, then Mental Health, then Therapy, then your region. This model was high quality because it was human verified, but it was fundamentally unscalable. As the web grew exponentially, the ratio of human editors to web pages collapsed. It was like a card catalog trying to organize a library that was printing a million new books every day.

Competitors like AltaVista and Excite used “lexical” search. They simply counted how many times a word appeared on a page. If you searched for “trauma,” AltaVista returned the page with the highest frequency of the word “trauma.” This led to the first generation of SEO manipulation: keyword stuffing. If you wanted to rank, you repeated “trauma” 5,000 times in white text on a white background, invisible to humans but visible to the crawler. The “message” became pure noise. The search results were a wasteland of spam.

Google entered the market late, in 1998, but decimated its competitors because it changed the definition of “relevance” from what you say to who trusts you.

Larry Page and Sergey Brin realized that the hyperlink was not just a navigation tool. It was a citation. They invented PageRank, an algorithm that treated every link pointing to a website as a “vote” of confidence. A link from a high-authority site, like a university or a major newspaper, counted more than a link from a personal blog. Google provided cleaner, more relevant results than AltaVista because it relied on the collective intelligence of the web’s structure rather than just the text on the page.

This was elegant. It was also the beginning of the end of the wild web. Because now, to exist, you needed other people to vouch for you. Connectivity became currency. You did not exist unless someone else linked to you.

The Content Farms and the Skyscraper

As Google’s dominance grew, marketers realized they could reverse-engineer the math. The decade from 2000 to 2010 became the Industrial Revolution of SEO.

Companies realized that Google’s algorithm rewarded freshness and quantity. They built massive content farms, operations like Demand Media and eHow, that identified millions of “long-tail keywords” (specific search queries like “how to boil an egg” or “how to deal with anxiety at night”). They paid freelancers pennies to write thousands of low-quality articles a day. The internet flooded with shallow content designed for robots, not humans. The message became generic and diluted.

To compete, independent bloggers adopted what became known as the Skyscraper Technique. If the top result for “trauma therapy” was 1,000 words, you had to write 2,000 words to beat it. If someone wrote 2,000, you wrote 4,000. The algorithm rewarded “comprehensiveness,” so comprehensiveness was manufactured regardless of whether it served the reader.

This is why I cannot just post a simple, helpful insight about grounding techniques. To rank, I must write a “definitive guide,” bloating my message to satisfy the algorithm’s hunger for length. The person in crisis who just needs to know what to do has to scroll past thousands of words of context because the machine cannot distinguish between depth and padding.

Why You Cannot Read a Recipe Without Reading Someone’s Life Story

Around 2011, Google released two massive updates, Panda and Penguin, designed to punish “thin” content and “unnatural” links. The content farms collapsed. But the updates created a new problem that anyone who has tried to find a recipe online will recognize immediately.

You cannot read a recipe without reading someone’s life story.

This phenomenon is not an accident. It is a direct consequence of how the algorithm evaluates quality.

Google cannot taste a recipe to see if it is good. It cannot distinguish between a “good” Chicken Tikka Masala and a “bad” one based on the ingredients list alone. Furthermore, a list of ingredients is data, not creative content. It is not protected by copyright. If a blogger posted a simple recipe, it could be scraped by an aggregator and duplicated across the web.

Food bloggers discovered that wrapping the recipe in a 2,000-word personal narrative solved three algorithmic problems simultaneously.

First, the story about the “vacation in the Adirondacks” is unique. No other site has that specific string of text. By attaching the recipe to the story, the page becomes a unique, copyrightable asset that Google’s “duplicate content” filters identify as the original source. The narrative is the fingerprint that proves ownership.

Second, a recipe that just says “Chicken, Yogurt, Spices” ranks only for “Chicken Tikka Masala,” a highly competitive term. But a story that mentions “comforting autumn dinner for a large family after a hiking trip” allows the page to rank for hundreds of additional long-tail keywords like “autumn dinner ideas” or “meals for large families.” The narrative expands the surface area of the content.

Third, Google uses user behavior signals like “time on page” as a proxy for quality. If a user clicks a recipe, reads “1 cup flour,” and leaves in 10 seconds, Google thinks the result was bad. If a user clicks, has to scroll past ads, photos, and a story about a grandmother, and spends 2 minutes on the page hunting for ingredients, Google thinks this must be a fascinating page worth promoting. Friction became a ranking factor. The annoyance of the user was interpreted by the machine as engagement.

This is the algorithm reshaping human communication. Not because anyone intended it. But because the medium has its own logic, and that logic optimizes for what it can measure.

The Pivot to Video: A Metric-Driven Hallucination

Around 2015, something happened that revealed how completely platforms can distort reality.

Facebook began reporting explosive growth in video consumption. Mark Zuckerberg claimed that the future of the internet was “all video,” predicting that text would become obsolete. Publishers, desperate to chase the audience and the advertising dollars that followed them, fired hundreds of writers and “pivoted” to video production. Entire newsrooms were liquidated. Deep, nuanced reporting was replaced by 30-second captioned videos designed to be watched without sound.

It was later revealed that Facebook had inflated its video metrics by 60% to 80%. They counted a “view” even if a user scrolled past a muted, auto-playing video for just 3 seconds. The “engagement” was a hallucination. A lawsuit filed by advertisers alleged that the discrepancy was as high as 150% to 900%, and that Facebook had known about the problem for over a year before disclosing it. Remember these are the same things that ended a company like Enron in 2001, but in 2015 we barely blinked. People had become used to Wall street valuations being a casino no longer tied to realistic valuations.

By the time the truth emerged, an entire generation of text-based journalism and nuance had been wiped out based on a lie. Facebook eventually settled the lawsuit for $40 million, admitting no wrongdoing. But the publishers who had already pivoted, who had made big cuts or shut down completely when it turned out people weren’t actually watching, got nothing back.

For a trauma blog, this era was dangerous. Healing work requires depth, patience, and safety. Video algorithms thrive on arousal, shock, and speed. A therapist trying to explain the Window of Tolerance in a 15-second Reel is forced to strip away the nuance, potentially turning a therapeutic concept into a pop-psychology soundbite. The medium actively resists the message.

The Medic Update: When Google Became the Arbiter of Medical Truth

For anyone running a health-related website, the most critical turning point was August 1, 2018. Google released what became known as the “Medic” Update, and it changed everything.

Following the “fake news” crisis of 2016, Google came under pressure to curate “truth” in sensitive sectors. They categorized certain topics as YMYL (Your Money or Your Life): pages that could impact a person’s future happiness, health, financial stability, or safety. Psychotherapy and trauma fall squarely into this category.

To police YMYL content, Google introduced E-E-A-T as a major ranking factor: Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness.

Expertise means: Does the author have formal credentials (MD, PhD, LCSW)?

Authoritativeness means: Is the site cited by “consensus” institutions like the CDC, the Mayo Clinic, or universities?

Trustworthiness means: Is the information aligned with “scientific consensus”?

This sounds reasonable until you consider what it means for innovation. “New” modalities, the kind I was trying to fund, often lack the multi-decade Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) that Google’s “trusted” sources rely on. A blog post about Cognitive Behavioral Therapy ranks easily because it is backed by “consensus.” A blog post about a newer somatic modality might be flagged as “low quality” or “misinformation” if it makes claims that aren’t supported by WebMD or the CDC.

This is what philosophers call “epistemic paternalism”: the algorithm acts as a parent, shielding the user from “unsafe” ideas, assuming the user cannot evaluate them for themselves. The problem is that the algorithm cannot distinguish between dangerous misinformation and legitimate innovation that hasn’t yet accumulated enough institutional citations.

To rank, I had to perform authority. I had to add formal bios with credentials. I had to link to “authoritative” sources that might actively disagree with my holistic approach. I had to adopt a clinical tone. The warm, personal, community-based voice of a healing collective often fails E-E-A-T checks. The algorithm prefers the sterile, objective tone of a medical journal.

The medium forced me to validate my work through the lens of the very biomedical establishment I was trying to offer an alternative to. To speak about experiential therapy, I had to sound like the cognitive-behavioral establishment.

The Billion-Dollar Crawl

To understand why Google enforces these constraints, you must understand the economics of indexing.

Google processes over 5 trillion searches per year. To do this, it must dispatch a bot (Googlebot) to request a page, download the HTML, parse the code, extract the text and links, and store it in a massive database. This costs money. A lot of money.

Testimony in the U.S. vs Google antitrust trial revealed that Google paid $26.3 billion in 2021 just to remain the default search engine on mobile phones and web browsers. The total infrastructure cost for search and indexing runs into the billions annually. Every millisecond of processing time consumes electricity. Every gigabyte of storage costs money.

Because of this cost, Google assigns a “crawl budget” to every website. If a site is slow, messy, or difficult to parse, the bot leaves before indexing everything. This creates relentless pressure for “technical SEO”: clean code, standard fonts, minimal clutter, fast load times.

Why do all modern websites look the same? Why do they all use clean grids and predictable structures? Because “clean” code is cheaper for Google to parse. A complex, artistic, experimental website, like the Flash sites of the early 2000s, is expensive to index. Google’s algorithm punishes “inefficient” creativity.

The algorithm cannot afford to index “messy” human reality. It demands schema markup, predictable structures, and standardized formats. The wildness of human expression must be flattened into the geometry of a database.

The Pre-Filtered Reality

This brings us back to Adam Curtis and the concept of perception management.

The web pages you see have been pre-selected. They have been filtered by an algorithm that rewards conformity to its structure. If content does not fit the algorithm’s preferences, it does not appear in search results. If it does not appear in search results, for most practical purposes, it does not exist.

Google’s autocomplete and “People Also Ask” features create feedback loops. When you type “Is trauma…”, Google suggests completions based on what others have searched. This homogenizes curiosity. We stop asking our own idiosyncratic questions and start asking the crowd’s questions. If the algorithm suggests “Is trauma genetic?”, the user is primed to think about genetics, diverted from other lines of inquiry like “Is trauma systemic?” or “Is trauma stored in the body?”

If the algorithm prioritizes biomedical questions (“symptoms of PTSD“), it frames the user’s self-conception as a “patient” with a “disorder.” If it prioritized somatic questions (“how trauma is held in the body”), the user might frame themselves differently. The algorithm chooses the frame before the user arrives.

Research suggests we are offloading our memory to the internet, a phenomenon called the “Google Effect.” We no longer remember facts; we remember how to find facts. For therapists, this changes how clients present. They arrive “pre-diagnosed” by the algorithm. They have consumed the top-performing content, which is consensus-based and likely biomedical, and may be resistant to modalities that contradict what the search results told them. The therapist is no longer just treating the client. The therapist is treating the client’s algorithmic conditioning.

The Zero-Click Future

We are now entering the most disruptive phase since 1998: the transition from Search Engines to Answer Engines.

For 25 years, the social contract of the web was simple. You create content, Google indexes it, and Google sends you traffic. With AI Overviews, Google is breaking this contract. The AI scrapes your blog, synthesizes the answer, and presents it directly on the search page. The user gets the information. You get zero clicks.

If a user searches “What is Somatic Experiencing?”, Google’s AI will generate an answer on the search page, drawing from content creators like me without sending anyone to my site. If I rely on traffic to fund the collective, this model is an existential threat. Estimates suggest that over half of all Google searches now end without a click to any website.

Google faces a paradox. To train its AI, it needs fresh, high-quality human content. But if it stops sending traffic to creators, creators will stop creating. The AI will eventually start training on its own output, leading to what researchers call “model collapse,” a degradation of truth as the machine feeds on its own hallucinations.

This is the central tension of the next five years. Google needs us to write. But its business model needs to stop users from visiting us.

The Algorithmic Self

When I started this blog, I thought I was writing for humans. I thought the challenge was finding words that would reach people who were suffering, words that would communicate something true about healing.

I was naive.

The challenge is not writing for humans. The challenge is writing for machines in a way that humans can still recognize themselves in the text. The challenge is satisfying the algorithm’s demand for structure, authority, and length while preserving something of the warmth and nuance that healing actually requires.

Over four years, I have changed my content, my formatting, my presentation, and even my tone to satisfy the preference of an algorithm that does not know what trauma is, that cannot feel what it means to be held in a safe relational space, that has no concept of the body or the nervous system or the long slow work of integration.

And here is the disturbing part: I have started to think like the algorithm. When I sit down to write, part of my brain is already editing for keywords, for headers, for “scanability.” I find myself asking: “Is this paragraph too long?” “Is this keyword in the H2?” “Will this capture a Featured Snippet?”

We are training ourselves to think like machines to be understood by machines. The human element is preserved only insofar as it serves a metric.

The Mirror We Built

The internet is not a cloud. It is a mirror. But it is a funhouse mirror, curved by the gravitational pull of Google’s billion-dollar crawling budget, polished by the Medic Update’s demand for consensus, and fractured by the Pivot to Video and the Recipe Blog wars.

Curtis argued in HyperNormalisation that we accept manufactured reality because we cannot imagine an alternative. We accept the algorithm’s curation of truth because we cannot imagine finding information any other way. We accept that to speak about healing, we must sound like the institutions that have historically marginalized body-based approaches. We accept that to be visible, we must conform.

For the Birmingham trauma collective, the internet has been both a lifeline and a cage. It provided the visibility to fund healing. But it demanded that the healing be packaged in a box designed by engineers who have never met a patient. The medium required the message to become standardized, optimized, and safe.

The task now is to resist the total flattening of this experience. As we move into the AI era, the most valuable asset will not be the “optimized” content that mimics the machine, but the raw, messy, un-optimizable human truth that the machine can witness but never truly replicate.

The body-brain connection that we work with in therapy cannot be reduced to schema markup. The felt sense of trauma cannot be captured in a Featured Snippet. The relational field between therapist and client cannot be indexed.

These are the things that remain human. These are the things the algorithm can scrape but never understand.

And perhaps, in the end, that is the only resistance available to us: to keep speaking in the human register, even as we translate ourselves into Algorithmic English to be heard.

References and Further Reading

Media Theory:

Wikipedia: The Medium Is the Message

Wikipedia: HyperNormalisation (Adam Curtis)

Search Engine History:

SEO and Google Updates:

Google: Creating Helpful Content (E-E-A-T Guidelines)

Schema.org: Structured Data Standards

Economics of Search:

CNBC: Google Paid $26 Billion for Default Search Status

Zyppy: Google’s Index Size Revealed

Pivot to Video:

Nieman Lab: Facebook’s Faulty Video Metrics

Psychology of Search:

APA: The Google Effect on Memory

Zero-Click Search:

SparkToro: Zero-Click Search Statistics

0 Comments