Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory: Architecture, Ambition, and the Anatomy of Its Decline

Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory stands as one of the most ambitious intellectual projects of the late twentieth century, attempting nothing less than a comprehensive synthesis of human knowledge across all domains of inquiry. From its emergence in the 1970s through its peak influence in the early 2000s to its current marginal status in academic and clinical circles, the trajectory of Integral Theory offers profound lessons about the possibilities and perils of grand theoretical synthesis in our fragmented intellectual landscape.

The Genesis and Architecture of Integral Theory

Ken Wilber burst onto the intellectual scene in 1977 with “The Spectrum of Consciousness,” written when he was just twenty-three years old. This work proposed a developmental model that integrated Western psychology with Eastern contemplative traditions, suggesting that different therapeutic and spiritual approaches addressed different levels of the spectrum of human consciousness. This initial synthesis would evolve over the subsequent decades into what Wilber would eventually call Integral Theory, or simply “AQAL” (All Quadrants, All Levels, All Lines, All States, All Types).

The core insight driving Wilber’s work was deceptively simple: every field of human knowledge contains partial truths, and these partial truths can be organized into a coherent meta-framework that honors their contributions while transcending their limitations. Where postmodernism had deconstructed grand narratives and left us with relativistic fragments, Wilber sought to reconstruct a new kind of grand narrative that could accommodate multiple perspectives without reducing them to a single dogma.

The fundamental architecture of Integral Theory rests on several key components that Wilber argued were irreducible dimensions of reality. The Four Quadrants represent the most basic division: the interior and exterior dimensions of both individual and collective phenomena. The Upper Left quadrant encompasses subjective experience, intentionality, and consciousness. The Upper Right contains objective behavior and the physical correlates of consciousness. The Lower Left holds intersubjective cultural meanings, shared values, and mutual understanding. The Lower Right includes interobjective systems, social structures, and ecological networks.

This quadrant model attempts to solve the perennial philosophical problem of how to relate mind and matter, individual and society, by suggesting that these are not separate entities but rather different perspectives on the same holistic reality. Every phenomenon, Wilber argued, simultaneously arises in all four quadrants, and any attempt to reduce reality to just one quadrant inevitably creates distortions and pathologies.

Building on this foundation, Wilber incorporated developmental levels, drawing heavily from the work of developmental psychologists like Jean Piaget, Lawrence Kohlberg, and Jane Loevinger, as well as contemplative traditions that mapped stages of spiritual realization. These levels, which Wilber often depicted using color-coding from Spiral Dynamics, suggest that human consciousness evolves through increasingly complex and inclusive stages, from archaic to magic to mythic to rational to pluralistic to integral and beyond.

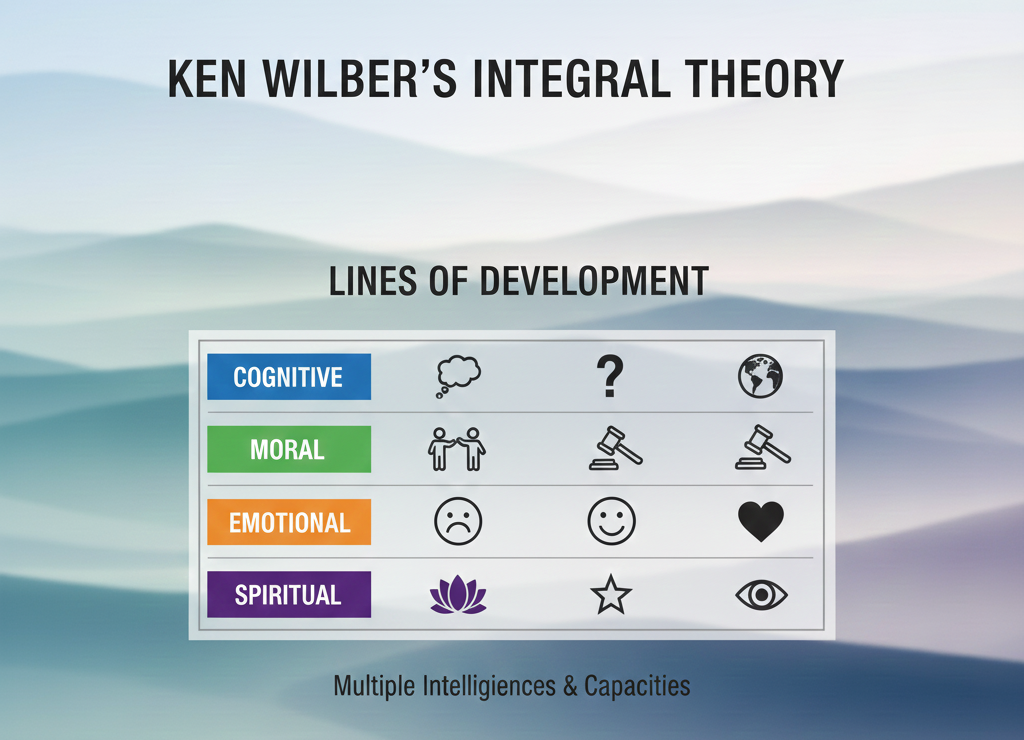

The theory further elaborated multiple developmental lines or intelligences, acknowledging that development doesn’t proceed uniformly across all capacities. Someone might be highly developed cognitively while remaining at an earlier stage morally or spiritually. This addressed a common criticism of stage theories that seemed to suggest a monolithic progression of human development.

States of consciousness formed another crucial dimension, distinguishing between the temporary states accessible through meditation, psychedelics, or peak experiences, and the stable stages of development that unfold over time. Types referred to consistent patterns or styles that persist across levels, such as personality types or gender expressions. Together, these elements formed the AQAL model, which Wilber presented as a comprehensive map of human and cosmic evolution.

The Mechanisms and Applications of Integral Theory

The practical application of Integral Theory extended far beyond abstract philosophy. Wilber and his followers developed Integral Life Practice, a comprehensive approach to personal development that addressed body, mind, spirit, and shadow dimensions simultaneously. This wasn’t merely eclecticism but a systematic attempt to engage multiple dimensions of human development in a coordinated fashion.

In psychotherapy, Integral Theory promised to transcend the wars between different therapeutic schools by showing how each approach addressed different levels of the spectrum of consciousness. Cognitive-behavioral therapy might work best for rational-level issues, while transpersonal approaches were needed for spiritual emergencies, and somatic therapies addressed pre-verbal traumas lodged in the body. This integral psychotherapy would skillfully match interventions to the client’s developmental level and the nature of their concerns.

The Integral Institute, founded in 1998, brought together leading thinkers from diverse fields to apply integral principles to education, business, politics, medicine, and ecology. Integral Education sought to address all dimensions of human development rather than just cognitive intelligence. Integral Business claimed to offer a more comprehensive approach to organizational development that honored both efficiency and meaning, profits and purpose. Integral Politics attempted to transcend the limitations of both liberal and conservative ideologies by recognizing the partial truths in each perspective.

The methodology underlying these applications involved what Wilber called Integral Methodological Pluralism, which recognized eight fundamental methodologies corresponding to different perspectives on the four quadrants. Phenomenology explored first-person subjective experience. Structuralism mapped the patterns of that experience. Autopoiesis theory examined individual behavior and neuroscience. Empiricism measured objective outcomes. Hermeneutics interpreted cultural meanings. Ethnomethodology studied how those meanings were enacted. Social systems theory analyzed collective structures. And ecology examined the networks of relationships between systems.

This methodological pluralism promised to end the paradigm wars that had fractured academia by showing how different methodologies were accessing different dimensions of the same integral reality. Rather than arguing whether consciousness should be studied through neuroscience or phenomenology, Integral Theory suggested both approaches were necessary and complementary.

The Decline and Critique of Integral Theory

Despite its initial promise and the enthusiasm it generated among certain circles of intellectuals and practitioners, Integral Theory has largely failed to achieve mainstream academic acceptance or lasting cultural influence. Understanding this failure requires examining both the internal contradictions of the theory itself and the sociological dynamics of how knowledge communities form and fragment.

The most fundamental critique concerns the theory’s claim to have transcended and included all previous knowledge while simultaneously positioning itself as a view from nowhere—or everywhere. Critics argued that Wilber’s synthesis was inevitably selective, privileging certain thinkers and traditions while marginalizing others. The theory claimed to honor indigenous wisdom traditions, for example, but often reduced complex cosmologies to simplified developmental stages that reinforced a fundamentally Western, progressive narrative of human evolution.

The developmental model at the heart of Integral Theory came under sustained attack from multiple directions. Postcolonial scholars pointed out how stage theories had historically been used to justify colonialism by positioning Western rationality as more evolved than indigenous ways of knowing. Feminist scholars critiqued the linear, hierarchical nature of the developmental stages as reflecting masculine biases toward separation and transcendence rather than connection and immanence. Postmodern critics argued that the very notion of universal stages of development was a modernist fiction that ignored the radical diversity of human experience and the ways power shapes what counts as “development.”

Wilber’s response to these critiques often exacerbated the problem. He dismissed many critics as coming from “lower” developmental levels, unable to understand Integral Theory because they hadn’t evolved to an integral stage of consciousness. This circular reasoning—where disagreement was evidence of inferior development—created an insular community of believers rather than an open intellectual discourse. The theory that promised to integrate all perspectives paradoxically became a closed system that could only be truly understood by those who already accepted its premises.

The empirical basis of Integral Theory also proved problematic. While Wilber drew on extensive research from developmental psychology, much of this research has been challenged or superseded in recent decades. The clean stages proposed by earlier theorists have given way to more complex, non-linear models of development that recognize multiple pathways and cultural variations. The neuroscience that Wilber cited to support his spectrum of consciousness has advanced considerably, often in directions that don’t support his neat correlations between brain states and consciousness stages.

The institutional dynamics around Integral Theory further contributed to its marginalization. The Integral Institute, rather than becoming a genuinely transdisciplinary research center, increasingly functioned as an echo chamber for true believers. Academic scholars who initially engaged with Integral Theory often distanced themselves as it became associated with New Age spirituality rather than rigorous scholarship. The commercialization of Integral Theory through expensive workshops, certification programs, and lifestyle products undermined its credibility as a serious intellectual framework.

Moreover, the personality cult that developed around Wilber himself became a liability. His increasingly dogmatic pronouncements, his dismissal of critics, and his claims to enlightenment created a guru-disciple dynamic that was antithetical to open intellectual inquiry. When Wilber experienced health challenges and withdrew from public engagement, the movement lost its charismatic center without having developed institutional structures or intellectual leadership to carry it forward.

The practical applications of Integral Theory also failed to demonstrate clear superiority over existing approaches. Integral psychotherapy, while offering a useful heuristic for thinking about different therapeutic interventions, didn’t produce measurably better outcomes than well-established therapeutic approaches. Integral business consulting often reduced to conventional organizational development with added spiritual vocabulary. Integral politics never transcended the culture wars it claimed to resolve, instead creating its own tribal identity that was just as partial as the perspectives it critiqued.

The Contemporary Relevance and Lessons

Despite its failures as a grand unified theory, Integral Theory’s influence persists in subtle ways and offers important lessons for contemporary efforts at theoretical synthesis. The AQAL framework, stripped of its more grandiose claims, provides a useful heuristic for ensuring that multiple perspectives are considered in addressing complex problems. The recognition that interior subjective experience and exterior objective behavior, individual development and collective systems, all need to be considered remains valuable even if we reject the specific ways Wilber mapped these dimensions.

The failure of Integral Theory also illuminates the challenges facing any attempt at comprehensive theoretical synthesis in our current intellectual climate. The dream of a theory of everything seems increasingly naive in an era that has witnessed the proliferation of knowledge domains, each with their own specialized languages, methods, and standards of validation. The postmodern critique of grand narratives, which Wilber sought to overcome, may reflect not just intellectual fashion but a genuine recognition of the irreducible plurality of human experience and ways of knowing.

Yet the hunger that Integral Theory addressed—for meaning, coherence, and connection across fragmented domains of knowledge—remains acute. The mental health crisis, ecological catastrophe, and social fragmentation of our time call for approaches that can work across multiple dimensions simultaneously. The failure of Integral Theory might not mean abandoning integration altogether but rather pursuing more modest, pragmatic, and pluralistic forms of synthesis that don’t claim to have achieved a final, comprehensive framework.

The trajectory of Integral Theory also offers a cautionary tale about the sociology of knowledge and the dynamics of intellectual movements. The initial enthusiasm generated by a new theoretical framework can create a community of believers who become increasingly isolated from broader intellectual currents. The need for institutional support and financial sustainability can lead to commercialization that undermines scholarly credibility. The charisma of a founding figure can both catalyze a movement and ultimately limit its development.

For practitioners in fields like psychotherapy, education, and organizational development, the legacy of Integral Theory might be less a specific framework to apply than a reminder of the importance of theoretical pluralism and pragmatic integration. Rather than seeking the one true theory that explains everything, we might cultivate the capacity to move fluidly between different theoretical lenses, recognizing that each illuminates certain aspects of reality while obscuring others.

The rise and fall of Integral Theory also speaks to deeper cultural dynamics around spirituality, science, and meaning-making in late modernity. Wilber’s attempt to create a “theory of everything” that included both scientific materialism and spiritual transcendence reflected a widespread desire to heal the split between facts and values, matter and consciousness, that has characterized Western thought since the Enlightenment. That this attempt ultimately failed doesn’t negate the legitimacy of the desire or the importance of continuing to seek ways of knowing that honor both the rational and the trans-rational, the empirical and the experiential.

Integration Without Totalization

The story of Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory is ultimately a story about the possibilities and limitations of human knowledge, the tension between the drive toward comprehensive understanding and the recognition of irreducible plurality, the challenge of creating inclusive frameworks that don’t become exclusive ideologies. Its failure as a grand unified theory of everything might paradoxically be its greatest teaching, pointing us toward forms of integration that remain open, provisional, and humble rather than closed, final, and grandiose.

For contemporary thinkers and practitioners, the lesson might be to pursue integration without totalization, to seek connections across domains of knowledge without claiming to have achieved a final synthesis, to honor multiple perspectives without arranging them in a rigid hierarchy of development. The quadrants might serve as a useful reminder to consider multiple dimensions of any phenomenon without claiming these are the only or ultimate dimensions. The developmental levels might sensitize us to the reality of growth and transformation without imposing a single trajectory on the diverse paths of human becoming.

The failure of Integral Theory also invites us to examine our own hunger for comprehensive meaning-making frameworks and to question whether this hunger might sometimes lead us away from rather than toward genuine understanding. Perhaps the fragmentation of knowledge that Wilber sought to overcome is not simply a problem to be solved but also a reflection of the genuine complexity and mystery of existence that resists final systematization.

In the end, Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory stands as a magnificent failure—a bold, brilliant, and ultimately unsustainable attempt to create a theory of everything. Its collapse doesn’t diminish the brilliance of the attempt or the insights generated along the way, but it does suggest that the future of integrative thinking lies not in grand unified theories but in more modest, flexible, and pluralistic approaches to connecting the fragments of our knowledge and experience. The integral impulse—to see connections, to honor multiple perspectives, to seek coherence without imposing uniformity—remains vital even as the specific framework of Integral Theory recedes into intellectual history.

The practitioners and thinkers who were inspired by Integral Theory have largely moved on, taking with them certain insights while abandoning the totalizing framework. They work in the spaces between disciplines, seeking pragmatic integrations that serve specific purposes rather than claiming universal validity. They recognize that the map is not the territory, that all theories are partial and provisional, and that the mystery of existence always exceeds our attempts to comprehend it fully. In this more humble but perhaps more honest stance toward the complexity of reality, the true legacy of Integral Theory might be found—not as the theory of everything it claimed to be, but as a reminder of both the importance and the limits of our integrative aspirations.

Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory stands as one of the most ambitious intellectual projects of the late twentieth century, attempting nothing less than a comprehensive synthesis of human knowledge across all domains of inquiry. From its emergence in the 1970s through its peak influence in the early 2000s to its current marginal status in academic and clinical circles, the trajectory of Integral Theory offers profound lessons about the possibilities and perils of grand theoretical synthesis in our fragmented intellectual landscape.

The Genesis and Architecture of Integral Theory

Ken Wilber burst onto the intellectual scene in 1977 with “The Spectrum of Consciousness,” written when he was just twenty-three years old. This work proposed a developmental model that integrated Western psychology with Eastern contemplative traditions, suggesting that different therapeutic and spiritual approaches addressed different levels of the spectrum of human consciousness. This initial synthesis would evolve over the subsequent decades into what Wilber would eventually call Integral Theory, or simply “AQAL” (All Quadrants, All Levels, All Lines, All States, All Types).

The core insight driving Wilber’s work was deceptively simple: every field of human knowledge contains partial truths, and these partial truths can be organized into a coherent meta-framework that honors their contributions while transcending their limitations. Where postmodernism had deconstructed grand narratives and left us with relativistic fragments, Wilber sought to reconstruct a new kind of grand narrative that could accommodate multiple perspectives without reducing them to a single dogma.

The fundamental architecture of Integral Theory rests on several key components that Wilber argued were irreducible dimensions of reality. The Four Quadrants represent the most basic division: the interior and exterior dimensions of both individual and collective phenomena. The Upper Left quadrant encompasses subjective experience, intentionality, and consciousness—domains explored by phenomenological research in psychology and contemplative neuroscience studies. The Upper Right contains objective behavior and the physical correlates of consciousness, as studied by behavioral neuroscience and cognitive science. The Lower Left holds intersubjective cultural meanings, shared values, and mutual understanding—the domain of cultural psychology and anthropological research. The Lower Right includes interobjective systems, social structures, and ecological networks studied by systems theory and social network analysis.

This quadrant model attempts to solve the perennial philosophical problem of how to relate mind and matter, individual and society, by suggesting that these are not separate entities but rather different perspectives on the same holistic reality. Every phenomenon, Wilber argued, simultaneously arises in all four quadrants, and any attempt to reduce reality to just one quadrant inevitably creates distortions and pathologies.

Building on this foundation, Wilber incorporated developmental levels, drawing heavily from the work of developmental psychologists like Jean Piaget, Lawrence Kohlberg, and Jane Loevinger, as well as contemplative traditions that mapped stages of spiritual realization. These levels, which Wilber often depicted using color-coding from Spiral Dynamics, suggest that human consciousness evolves through increasingly complex and inclusive stages, from archaic to magic to mythic to rational to pluralistic to integral and beyond.

The theory further elaborated multiple intelligences or developmental lines, acknowledging that development doesn’t proceed uniformly across all capacities. Someone might be highly developed cognitively while remaining at an earlier stage morally or spiritually. This addressed a common criticism of stage theories that seemed to suggest a monolithic progression of human development.

States of consciousness formed another crucial dimension, distinguishing between the temporary states accessible through meditation research, psychedelic therapy studies, or peak experiences, and the stable stages of development that unfold over time. Types referred to consistent patterns or styles that persist across levels, such as personality types or gender expressions. Together, these elements formed the AQAL model, which Wilber presented as a comprehensive map of human and cosmic evolution.

The Mechanisms and Applications of Integral Theory

The practical application of Integral Theory extended far beyond abstract philosophy. Wilber and his followers developed Integral Life Practice, a comprehensive approach to personal development that addressed body, mind, spirit, and shadow dimensions simultaneously. This wasn’t merely eclecticism but a systematic attempt to engage multiple dimensions of human development in a coordinated fashion, similar to modern integrative medicine approaches.

In psychotherapy, Integral Theory promised to transcend the wars between different therapeutic schools by showing how each approach addressed different levels of the spectrum of consciousness. Cognitive-behavioral therapy might work best for rational-level issues, while transpersonal approaches were needed for spiritual emergencies, and somatic therapies addressed pre-verbal traumas lodged in the body. This integral psychotherapy would skillfully match interventions to the client’s developmental level and the nature of their concerns, an approach that resonates with contemporary evidence-based practice in psychology.

The Integral Institute, founded in 1998, brought together leading thinkers from diverse fields to apply integral principles to education, business, politics, medicine, and ecology. Integral Education sought to address all dimensions of human development rather than just cognitive intelligence. Integral Business claimed to offer a more comprehensive approach to organizational development that honored both efficiency and meaning, profits and purpose. Integral Politics attempted to transcend the limitations of both liberal and conservative ideologies by recognizing the partial truths in each perspective, similar to moral foundations theory in contemporary political psychology.

The methodology underlying these applications involved what Wilber called Integral Methodological Pluralism, which recognized eight fundamental methodologies corresponding to different perspectives on the four quadrants. Phenomenology explored first-person subjective experience. Structuralism mapped the patterns of that experience. Autopoiesis theory examined individual behavior and neuroscience. Empiricism measured objective outcomes. Hermeneutics interpreted cultural meanings. Ethnomethodology studied how those meanings were enacted. Social systems theory analyzed collective structures. And ecology examined the networks of relationships between systems.

This methodological pluralism promised to end the paradigm wars that had fractured academia by showing how different methodologies were accessing different dimensions of the same integral reality. Rather than arguing whether consciousness should be studied through neuroscience or phenomenology, Integral Theory suggested both approaches were necessary and complementary.

The Decline and Critique of Integral Theory

Despite its initial promise and the enthusiasm it generated among certain circles of intellectuals and practitioners, Integral Theory has largely failed to achieve mainstream academic acceptance or lasting cultural influence. Understanding this failure requires examining both the internal contradictions of the theory itself and the sociological dynamics of how knowledge communities form and fragment.

The most fundamental critique concerns the theory’s claim to have transcended and included all previous knowledge while simultaneously positioning itself as a view from nowhere—or everywhere. Critics argued that Wilber’s synthesis was inevitably selective, privileging certain thinkers and traditions while marginalizing others. The theory claimed to honor indigenous wisdom traditions, for example, but often reduced complex cosmologies to simplified developmental stages that reinforced a fundamentally Western, progressive narrative of human evolution.

The developmental model at the heart of Integral Theory came under sustained attack from multiple directions. Postcolonial scholars pointed out how stage theories had historically been used to justify colonialism by positioning Western rationality as more evolved than indigenous ways of knowing. Feminist scholars critiqued the linear, hierarchical nature of the developmental stages as reflecting masculine biases toward separation and transcendence rather than connection and immanence. Postmodern critics argued that the very notion of universal stages of development was a modernist fiction that ignored the radical diversity of human experience and the ways power shapes what counts as “development.”

Wilber’s response to these critiques often exacerbated the problem. He dismissed many critics as coming from “lower” developmental levels, unable to understand Integral Theory because they hadn’t evolved to an integral stage of consciousness. This circular reasoning—where disagreement was evidence of inferior development—created an insular community of believers rather than an open intellectual discourse. The theory that promised to integrate all perspectives paradoxically became a closed system that could only be truly understood by those who already accepted its premises.

The empirical basis of Integral Theory also proved problematic. While Wilber drew on extensive research from developmental psychology, much of this research has been challenged or superseded in recent decades. The clean stages proposed by earlier theorists have given way to more complex, non-linear models of development that recognize multiple pathways and cultural variations. The neuroscience that Wilber cited to support his spectrum of consciousness has advanced considerably, often in directions that don’t support his neat correlations between brain states and consciousness stages.

The institutional dynamics around Integral Theory further contributed to its marginalization. The Integral Institute, rather than becoming a genuinely transdisciplinary research center, increasingly functioned as an echo chamber for true believers. Academic scholars who initially engaged with Integral Theory often distanced themselves as it became associated with New Age spirituality rather than rigorous scholarship. The commercialization of Integral Theory through expensive workshops, certification programs, and lifestyle products undermined its credibility as a serious intellectual framework.

Moreover, the personality cult that developed around Wilber himself became a liability. His increasingly dogmatic pronouncements, his dismissal of critics, and his claims to enlightenment created a guru-disciple dynamic that was antithetical to open intellectual inquiry. When Wilber experienced health challenges and withdrew from public engagement, the movement lost its charismatic center without having developed institutional structures or intellectual leadership to carry it forward.

The practical applications of Integral Theory also failed to demonstrate clear superiority over existing approaches. Integral psychotherapy, while offering a useful heuristic for thinking about different therapeutic interventions, didn’t produce measurably better outcomes than well-established therapeutic approaches. Integral business consulting often reduced to conventional organizational development with added spiritual vocabulary. Integral politics never transcended the culture wars it claimed to resolve, instead creating its own tribal identity that was just as partial as the perspectives it critiqued.

The Contemporary Relevance and Lessons

Despite its failures as a grand unified theory, Integral Theory’s influence persists in subtle ways and offers important lessons for contemporary efforts at theoretical synthesis. The AQAL framework, stripped of its more grandiose claims, provides a useful heuristic for ensuring that multiple perspectives are considered in addressing complex problems. The recognition that interior subjective experience and exterior objective behavior, individual development and collective systems, all need to be considered remains valuable even if we reject the specific ways Wilber mapped these dimensions.

The failure of Integral Theory also illuminates the challenges facing any attempt at comprehensive theoretical synthesis in our current intellectual climate. The dream of a theory of everything seems increasingly naive in an era that has witnessed the proliferation of knowledge domains, each with their own specialized languages, methods, and standards of validation. The postmodern critique of grand narratives, which Wilber sought to overcome, may reflect not just intellectual fashion but a genuine recognition of the irreducible plurality of human experience and ways of knowing.

Yet the hunger that Integral Theory addressed—for meaning, coherence, and connection across fragmented domains of knowledge—remains acute. The mental health crisis, ecological catastrophe, and social fragmentation of our time call for approaches that can work across multiple dimensions simultaneously. The failure of Integral Theory might not mean abandoning integration altogether but rather pursuing more modest, pragmatic, and pluralistic forms of synthesis that don’t claim to have achieved a final, comprehensive framework.

The trajectory of Integral Theory also offers a cautionary tale about the sociology of knowledge and the dynamics of intellectual movements. The initial enthusiasm generated by a new theoretical framework can create a community of believers who become increasingly isolated from broader intellectual currents. The need for institutional support and financial sustainability can lead to commercialization that undermines scholarly credibility. The charisma of a founding figure can both catalyze a movement and ultimately limit its development.

For practitioners in fields like psychotherapy, education, and organizational development, the legacy of Integral Theory might be less a specific framework to apply than a reminder of the importance of theoretical pluralism and pragmatic integration. Rather than seeking the one true theory that explains everything, we might cultivate the capacity to move fluidly between different theoretical lenses, recognizing that each illuminates certain aspects of reality while obscuring others.

The rise and fall of Integral Theory also speaks to deeper cultural dynamics around spirituality, science, and meaning-making in late modernity. Wilber’s attempt to create a “theory of everything” that included both scientific materialism and spiritual transcendence reflected a widespread desire to heal the split between facts and values, matter and consciousness, that has characterized Western thought since the Enlightenment. That this attempt ultimately failed doesn’t negate the legitimacy of the desire or the importance of continuing to seek ways of knowing that honor both the rational and the trans-rational, the empirical and the experiential.

Integration Without Totalization

The story of Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory is ultimately a story about the possibilities and limitations of human knowledge, the tension between the drive toward comprehensive understanding and the recognition of irreducible plurality, the challenge of creating inclusive frameworks that don’t become exclusive ideologies. Its failure as a grand unified theory of everything might paradoxically be its greatest teaching, pointing us toward forms of integration that remain open, provisional, and humble rather than closed, final, and grandiose.

For contemporary thinkers and practitioners, the lesson might be to pursue integration without totalization, to seek connections across domains of knowledge without claiming to have achieved a final synthesis, to honor multiple perspectives without arranging them in a rigid hierarchy of development. The quadrants might serve as a useful reminder to consider multiple dimensions of any phenomenon without claiming these are the only or ultimate dimensions. The developmental levels might sensitize us to the reality of growth and transformation without imposing a single trajectory on the diverse paths of human becoming.

The failure of Integral Theory also invites us to examine our own hunger for comprehensive meaning-making frameworks and to question whether this hunger might sometimes lead us away from rather than toward genuine understanding. Perhaps the fragmentation of knowledge that Wilber sought to overcome is not simply a problem to be solved but also a reflection of the genuine complexity and mystery of existence that resists final systematization.

In the end, Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory stands as a magnificent failure—a bold, brilliant, and ultimately unsustainable attempt to create a theory of everything. Its collapse doesn’t diminish the brilliance of the attempt or the insights generated along the way, but it does suggest that the future of integrative thinking lies not in grand unified theories but in more modest, flexible, and pluralistic approaches to connecting the fragments of our knowledge and experience. The integral impulse—to see connections, to honor multiple perspectives, to seek coherence without imposing uniformity—remains vital even as the specific framework of Integral Theory recedes into intellectual history.

The practitioners and thinkers who were inspired by Integral Theory have largely moved on, taking with them certain insights while abandoning the totalizing framework. They work in the spaces between disciplines, seeking pragmatic integrations that serve specific purposes rather than claiming universal validity. They recognize that the map is not the territory, that all theories are partial and provisional, and that the mystery of existence always exceeds our attempts to comprehend it fully. In this more humble but perhaps more honest stance toward the complexity of reality, the true legacy of Integral Theory might be found—not as the theory of everything it claimed to be, but as a reminder of both the importance and the limits of our integrative aspirations.

The Developmental Psychology Lineage

Jean Piaget: The Architecture of Cognitive Development

Jean Piaget’s genetic epistemology provided Wilber with the fundamental template for understanding development as a series of qualitatively distinct stages. Piaget’s observation that children don’t simply know less than adults but actually construct reality through fundamentally different cognitive structures became central to Wilber’s model. The Piagetian stages—sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational—offered Wilber a scientifically grounded framework for understanding the evolution of consciousness.

Wilber extended Piaget’s work beyond childhood development, arguing that cognitive development continues into adulthood through what he called “vision-logic” or “network-logic”—a stage beyond formal operations where the mind can hold multiple perspectives simultaneously without reducing them to a single framework. This extension drew from neo-Piagetian researchers like Michael Commons and Francis Richards, who proposed the existence of postformal stages of cognitive development.

However, Wilber’s use of Piaget has been criticized for oversimplifying the Swiss psychologist’s nuanced understanding of development. Piaget emphasized the active construction of knowledge through interaction with the environment, while Wilber sometimes presented stages as predetermined unfoldings of consciousness. Furthermore, contemporary developmental psychology research has moved beyond rigid stage theories to more dynamic systems approaches that Wilber’s model struggled to accommodate.

Lawrence Kohlberg: The Moral Dimension

Lawrence Kohlberg’s stages of moral development provided Wilber with a framework for understanding how ethical reasoning evolves from preconventional (punishment avoidance) through conventional (social conformity) to postconventional (universal principles) levels. Wilber saw in Kohlberg’s work evidence for his broader thesis that consciousness develops through increasingly inclusive circles of care and concern—from egocentric to ethnocentric to worldcentric to cosmocentric.

Wilber particularly drew on Kohlberg’s concept of hierarchical integration, where each stage transcends and includes the previous one. This became the “transcend and include” principle central to Integral Theory. However, Wilber’s application of Kohlberg’s work has been criticized for perpetuating the cultural biases that Carol Gilligan identified in her critique of Kohlberg’s male-centered conception of moral development.

Carol Gilligan: The Voice of Relationship

While initially overlooking her work, Wilber eventually incorporated Carol Gilligan’s ethics of care into his model, acknowledging that development could proceed through different but equally valid pathways. Gilligan’s distinction between the masculine ethics of justice (emphasized by Kohlberg) and the feminine ethics of care challenged Wilber to recognize that his developmental hierarchy might reflect gender biases.

Wilber responded by proposing that both masculine and feminine developmental lines exist, each with their own stages but following parallel trajectories. He suggested that healthy development involves integrating both agency (masculine) and communion (feminine) at each stage. However, feminist critics argued that Wilber still privileged the ascending, transcendent trajectory associated with masculinity over the descending, immanent path associated with femininity.

Jane Loevinger: Ego Development as Master Line

Jane Loevinger’s model of ego development became particularly important for Wilber because it seemed to integrate cognitive, moral, and interpersonal development into a single framework. Loevinger’s stages—from symbiotic through impulsive, self-protective, conformist, self-aware, conscientious, individualistic, autonomous, to integrated—provided a more holistic view of psychological development than purely cognitive or moral models.

Wilber interpreted Loevinger’s work as describing the development of the self-sense or “proximate self”—the navigator that moves through different states and stages of consciousness. He particularly emphasized her higher stages, seeing in the autonomous and integrated stages evidence for postconventional identity that could embrace paradox and multiple perspectives. Loevinger’s Washington University Sentence Completion Test became one of the few empirical measures that integral theorists used to assess developmental level.

Robert Kegan: The Evolving Self

Robert Kegan’s constructive-developmental theory profoundly influenced Wilber’s understanding of how consciousness develops through alternating periods of differentiation and integration. Kegan’s five orders of consciousness—from the incorporative through the impulsive, imperial, interpersonal, institutional, to the interindividual—mapped the evolution of subject-object relationships throughout the lifespan.

Wilber was particularly drawn to Kegan’s insight that development involves the gradual objectification of what was previously subject. What we are identified with (subject) at one stage becomes something we can observe and reflect upon (object) at the next stage. This process of “making object what was subject” became central to Wilber’s understanding of how meditation and psychotherapy facilitate development.

Kegan’s work also influenced Wilber’s understanding of the “embedding unconscious”—the invisible water in which our consciousness swims at each developmental level. However, Kegan himself has been cautious about Wilber’s use of his work, particularly the claim that spiritual realization represents a continuation of the same developmental process he studied.

Susanne Cook-Greuter: Postautonomous Ego Development

Susanne Cook-Greuter’s research on postautonomous stages of ego development provided Wilber with empirical evidence for development beyond the conventional endpoints recognized by academic psychology. Cook-Greuter identified two stages beyond Loevinger’s integrated stage: the construct-aware stage (where individuals become aware of the constructed nature of reality) and the unitive stage (characterized by a sense of unity with existence).

Wilber saw Cook-Greuter’s work as bridging the gap between conventional developmental psychology and contemplative traditions. Her research seemed to validate his claim that ordinary psychological development could continue into transpersonal or spiritual dimensions. Cook-Greuter initially collaborated with Wilber but later distanced herself from Integral Theory, concerned about the reification of stages and the hierarchical implications of the model.

Eastern Philosophy and Contemplative Traditions

Sri Aurobindo: The Integration of Matter and Spirit

The Indian philosopher-sage Sri Aurobindo provided Wilber with a sophisticated framework for understanding the relationship between evolution and involution, matter and spirit. Aurobindo’s integral yoga aimed at the transformation of human nature through the descent of supramental consciousness, offering a vision of spiritual development that didn’t reject the material world but sought to transform it.

Wilber drew heavily on Aurobindo’s concept of the “psychic being” (the evolving soul) and his detailed mapping of planes of consciousness from matter through vital, mental, overmental, and supramental levels. Aurobindo’s insight that evolution is the reverse process of involution—spirit involving itself in matter and then evolving back toward conscious realization—became foundational to Wilber’s cosmology.

However, scholars of Aurobindo have criticized Wilber for oversimplifying the Indian sage’s nuanced philosophy, particularly his understanding of the integral transformation of matter itself. Where Aurobindo envisioned the actual transformation of physical matter through spiritual force, Wilber tended toward a more metaphorical interpretation compatible with scientific materialism.

Nagarjuna and Madhyamika Buddhism

The Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna’s doctrine of emptiness (śūnyatā) profoundly influenced Wilber’s understanding of the relationship between form and emptiness. Nagarjuna’s tetralemma—the logical tool that negates all four possible positions (is, is not, both, neither)—provided Wilber with a way to think beyond the limitations of binary logic.

Wilber incorporated the Two Truths doctrine from Madhyamika Buddhism, distinguishing between relative truth (the world of forms and stages) and absolute truth (the emptiness underlying all forms). This allowed him to maintain his developmental hierarchy while acknowledging the ever-present ground of being that transcends all development. The notion that samsara and nirvana are not separate became central to his nondual philosophy.

Plotinus and Neoplatonism

The Neoplatonist philosopher Plotinus provided Wilber with the concept of the Great Chain of Being—a hierarchical structure of reality extending from matter through soul to spirit. Plotinus’s notion of emanation, where lower levels emerge from higher ones while the higher transcends and includes the lower, became fundamental to Wilber’s developmental model.

Wilber particularly drew on Plotinus’s understanding of the relationship between the One (the absolute ground of being) and the many (the manifest world). The Plotinian insight that consciousness can ascend through contemplation from identification with matter to union with the One influenced Wilber’s understanding of states of consciousness and the spiritual path.

Kashmir Shaivism

The Kashmir Shaivism tradition, particularly as interpreted through the work of Swami Muktananda and his lineage, influenced Wilber’s understanding of the relationship between consciousness and energy. The Shaivite concept of spanda (vibration) and the 36 tattvas (levels of reality) provided a detailed map of consciousness that Wilber incorporated into his spectrum model.

The Kashmir Shaivite emphasis on the world as the play (līlā) of consciousness, rather than as illusion (māyā), aligned with Wilber’s affirmation of the manifest world as a legitimate expression of spirit. The tradition’s sophisticated practices for recognizing the identity of individual consciousness with universal consciousness influenced his understanding of pointing-out instructions and state training.

Dzogchen Buddhism

The Dzogchen tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, particularly as taught by teachers like Chögyam Trungpa and Namkhai Norbu, provided Wilber with a sophisticated understanding of primordial awareness (rigpa) and the natural state. Dzogchen’s emphasis on the always-already present nature of enlightenment influenced his distinction between states (temporary) and the ever-present ground of being.

Wilber incorporated the Dzogchen teaching of the three statements of Garab Dorje: direct introduction to one’s nature, deciding upon this unique state, and continuing with confidence in liberation. This influenced his understanding of how pointing-out instructions could introduce practitioners to ever-present awareness regardless of their stage of development.

Western Philosophical Foundations

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Dialectical Development

Hegel’s dialectical philosophy provided Wilber with a model for understanding development as a process of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. The Hegelian notion that Spirit comes to know itself through the historical process of development became central to Wilber’s understanding of evolution as Spirit-in-action.

Wilber drew particularly on Hegel’s concept of Aufhebung—often translated as “sublation”—which means to simultaneously preserve, destroy, and transcend. This became Wilber’s “transcend and include” principle, where each developmental stage preserves the essential features of previous stages while negating their limitations and lifting them into a higher synthesis.

However, Wilber’s use of Hegel has been criticized by Hegelian scholars for oversimplifying the German philosopher’s complex dialectical method. Where Hegel emphasized the role of negativity and contradiction in driving development, Wilber tended toward a more harmonious vision of staged growth.

Jürgen Habermas: Communicative Rationality

Jürgen Habermas’s critical theory influenced Wilber’s understanding of the relationship between individual development and cultural evolution. Habermas’s theory of communicative action, which distinguished between instrumental rationality and communicative rationality, helped Wilber articulate how different types of knowledge claims require different validity criteria.

Wilber drew heavily on Habermas’s three validity claims—subjective truthfulness, intersubjective justness, and objective truth—which became the basis for his “Big Three” of art, morals, and science (corresponding to the Beautiful, Good, and True). Habermas’s critique of the colonization of the lifeworld by systems also influenced Wilber’s understanding of how techno-economic structures can dominate cultural and personal dimensions.

The discourse ethics developed by Habermas provided Wilber with a model for how post-conventional morality could be grounded in the structure of communication itself rather than in metaphysical assumptions. However, Habermas himself has been critical of attempts to extend his social theory into spiritual or transpersonal dimensions.

Alfred North Whitehead: Process Philosophy

Whitehead’s process philosophy influenced Wilber’s understanding of reality as composed of “actual occasions” of experience rather than static substances. Whitehead’s notion of prehension—how each moment of experience incorporates aspects of previous moments—provided a model for how development could involve both continuity and novelty.

Wilber incorporated Whitehead’s distinction between the consequent and primordial natures of God, seeing in this a philosophical articulation of the relationship between the manifest world of evolution and the unmanifest ground of being. Whitehead’s concept of the “creative advance into novelty” aligned with Wilber’s vision of evolution as Spirit’s creative expression.

Martin Heidegger: Being and Time

Heidegger’s existential phenomenology influenced Wilber’s understanding of the situated nature of human existence and the importance of temporality in consciousness. Heidegger’s concept of Dasein (being-there) as always already thrown into a world of meanings influenced Wilber’s understanding of the intersubjective dimension of consciousness.

Wilber drew on Heidegger’s distinction between ontic and ontological levels of analysis, using this to differentiate between the content of consciousness (ontic) and the structures of consciousness (ontological). Heidegger’s notion of authenticity as owned existence versus the fallenness of das Man (the they-self) influenced Wilber’s understanding of the transition from conformist to post-conventional stages of development.

Transpersonal Psychology Pioneers

Abraham Maslow: Self-Actualization and Beyond

Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and his later work on self-transcendence provided Wilber with a bridge between humanistic and transpersonal psychology. Maslow’s research on peak experiences and self-actualizing individuals offered empirical support for the existence of higher states of consciousness within a Western psychological framework.

Wilber extended Maslow’s hierarchy beyond self-actualization to include self-transcendence, seeing this as evidence that human development naturally progresses into spiritual dimensions. Maslow’s distinction between deficiency needs and being needs influenced Wilber’s understanding of the shift from deficiency-motivated to abundance-motivated consciousness at higher developmental stages.

Stanislav Grof: Cartography of the Psyche

Stanislav Grof’s research with LSD psychotherapy and holotropic breathwork provided Wilber with detailed maps of non-ordinary states of consciousness. Grof’s extended cartography of the psyche, including the biographical, perinatal, and transpersonal dimensions, influenced Wilber’s understanding of the full spectrum of consciousness.

Wilber incorporated Grof’s COEX systems (systems of condensed experience) into his understanding of how trauma and developmental fixations create distortions in consciousness. Grof’s concept of spiritual emergency as a developmental crisis influenced Wilber’s understanding of how growth often involves temporary regression and disorganization.

Carl Jung: The Collective Unconscious

Carl Jung’s analytical psychology provided Wilber with a sophisticated understanding of the unconscious and its role in development. Jung’s concepts of individuation, the shadow, archetypes, and the collective unconscious became important elements in Wilber’s model, particularly in understanding the pre-personal and personal stages of development.

However, Wilber critiqued what he called the “pre/trans fallacy” in Jung’s work, arguing that Jung sometimes confused pre-rational (infantile and regressive) with trans-rational (transcendent and progressive) states. This critique became central to Wilber’s attempt to distinguish authentic spiritual development from regression to pre-personal states.

Roberto Assagioli: Psychosynthesis

Roberto Assagioli’s psychosynthesis influenced Wilber’s understanding of the relationship between personal and transpersonal development. Assagioli’s egg diagram, mapping the lower unconscious, middle unconscious, higher unconscious, and superconscious, provided a vertical dimension to psychology that Wilber incorporated into his spectrum model.

Assagioli’s concept of the Higher Self and his techniques for dis-identification and self-identification influenced Wilber’s understanding of how contemplative practices facilitate development. The psychosynthesis emphasis on will and the integration of sub-personalities aligned with Wilber’s vision of integral life practice.

Systems Theory and Complexity Science

Ludwig von Bertalanffy: General Systems Theory

Ludwig von Bertalanffy’s general systems theory provided Wilber with a framework for understanding how wholes emerge from the interaction of parts. The concept of emergent properties—qualities that arise at higher levels of organization that cannot be predicted from lower levels—became central to Wilber’s understanding of developmental stages.

Wilber incorporated systems theory’s emphasis on hierarchy (or holarchy) as a natural organizing principle in nature, from atoms to molecules to cells to organisms to ecosystems. This provided scientific support for his developmental hierarchy of consciousness, though critics argued he oversimplified the complex dynamics of systems theory.

Arthur Koestler: The Holon

Arthur Koestler’s concept of the holon—something that is simultaneously a whole and a part—became fundamental to Wilber’s theoretical framework. Every entity in existence, Wilber argued, is a holon: a whole that contains parts while being part of a larger whole. This provided a non-reductionistic way to understand the relationship between different levels of reality.

Wilber elaborated twenty tenets of holons, describing their characteristics and dynamics. This holon theory became the foundation for his understanding of how individual development, cultural evolution, and cosmic evolution follow similar patterns of increasing complexity and integration.

Ervin Laszlo: Systems Philosophy

Ervin Laszlo’s systems philosophy and his work on evolutionary systems influenced Wilber’s understanding of evolution as a cosmic process tending toward greater complexity and consciousness. Laszlo’s concept of the Akashic field as an information field underlying physical reality resonated with Wilber’s understanding of the subtle dimensions of consciousness.

Wilber drew on Laszlo’s work to argue that evolution shows a direction—toward greater complexity, greater consciousness, and greater unity. This teleological view of evolution, while controversial in mainstream science, became central to Wilber’s cosmology.

Ilya Prigogine: Dissipative Structures

Ilya Prigogine’s work on dissipative structures and non-equilibrium thermodynamics influenced Wilber’s understanding of how order emerges from chaos. Prigogine’s insight that systems far from equilibrium can spontaneously organize into more complex structures provided a scientific model for understanding transformational change in consciousness.

Wilber incorporated Prigogine’s ideas about bifurcation points—moments when systems can suddenly shift to new levels of organization—into his understanding of developmental transitions. This helped explain why development often involves periods of chaos and disorganization before reorganizing at a higher level.

Structuralism and Post-Structuralism

Jean Gebser: Structures of Consciousness

Jean Gebser’s cultural phenomenology provided Wilber with a detailed map of the evolution of consciousness through history. Gebser’s five structures—archaic, magic, mythical, mental, and integral—became central to Wilber’s understanding of collective consciousness evolution.

Wilber was particularly influenced by Gebser’s notion of the integral structure as an aperspectival consciousness that could hold multiple perspectives simultaneously without being bound by any single perspective. This became Wilber’s vision of integral consciousness, though scholars of Gebser have argued that Wilber misunderstood Gebser’s non-developmental, non-hierarchical conception of these structures.

Claude Lévi-Strauss: Structural Anthropology

Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structural anthropology influenced Wilber’s understanding of the deep structures underlying surface features of consciousness. The structuralist insight that diverse cultural expressions share underlying patterns supported Wilber’s search for universal stages of development.

However, Wilber rejected the structuralist tendency to reduce consciousness to impersonal structures, arguing for the importance of both structures and their lived experience. His “structural phenomenology” attempted to integrate third-person structural analysis with first-person experiential exploration.

Michel Foucault: Power and Knowledge

Michel Foucault’s genealogical method and his analysis of power-knowledge relationships challenged Wilber to consider how developmental hierarchies might serve as instruments of power and normalization. Foucault’s critique of the human sciences as disciplines that create the subjects they study raised questions about whether developmental psychology was discovering or constructing stages.

Wilber acknowledged these concerns but argued that while power dynamics certainly influence how development is understood and valued, this doesn’t negate the reality of developmental processes. He attempted to incorporate Foucault’s insights about power while maintaining that some forms of development represent genuine growth rather than mere social construction.

Jacques Derrida: Deconstruction

Jacques Derrida’s deconstruction challenged the hierarchical oppositions that structured much of Western thought. Derrida’s critique of the “metaphysics of presence” and his concept of différance raised fundamental questions about Wilber’s hierarchical model and his claims to integrate all perspectives.

Wilber engaged with deconstruction by arguing that it represented a legitimate but partial perspective—specifically, the green meme or pluralistic stage in his color-coded system. He suggested that deconstruction’s critique of hierarchies was itself a developmental achievement that emerged at a particular stage of consciousness, and that integral consciousness could appreciate deconstruction’s insights while transcending its limitations.

The Synthesis and Its Discontents

Wilber’s synthesis of these diverse sources represents an extraordinary intellectual achievement, bringing together insights from traditions that rarely communicate with each other. His ability to find patterns across developmental psychology, Eastern philosophy, Western philosophy, and systems theory created a framework that has inspired thousands of practitioners and thinkers.

However, the very breadth of Wilber’s synthesis became a liability. Critics from each field argued that he oversimplified their disciplines’ insights to fit his grand scheme. Developmental psychologists pointed out that contemporary research has moved beyond simple stage theories. Buddhist scholars argued that he misunderstood key doctrines like emptiness and Buddha-nature. Critical theorists contended that he domesticated radical critiques into a conservative developmental hierarchy.

The question remains whether any individual, no matter how brilliant, can genuinely master such diverse fields sufficiently to create a valid synthesis. Wilber’s project may have been doomed from the start by its very ambition—the attempt to create a theory of everything necessarily involves simplifications and distortions that undermine the project’s credibility.

Moreover, the sociology of knowledge suggests that grand syntheses serve particular functions in specific historical moments. Wilber’s Integral Theory emerged during the 1980s and 1990s when globalization was creating a need for frameworks that could integrate diverse worldviews. Its decline in the 2000s and 2010s may reflect a shift toward appreciating irreducible diversity rather than seeking universal integration.

Contemporary Relevance and Future Directions

Despite its limitations, Wilber’s synthesis of these diverse thinkers offers valuable lessons for contemporary integral and integrative approaches:

- The importance of developmental thinking: Even if we reject rigid stages, understanding that consciousness can grow and evolve remains valuable for psychotherapy, education, and personal development.

- The value of multiple perspectives: The recognition that different thinkers and traditions offer partial truths that can complement each other remains important, even if we reject the claim to have achieved a final synthesis.

- The integration of East and West: Wilber’s attempt to bring together Western psychology and Eastern contemplative traditions paved the way for contemporary mindfulness-based interventions and contemplative psychotherapy.

- The need for post-metaphysical spirituality: Wilber’s attempt to articulate spirituality in terms compatible with modern science, while controversial, addresses a genuine need in our secular age.

The future of integrative thinking may lie not in grand theories that claim to synthesize everything but in more modest, pragmatic approaches that draw on multiple sources while remaining open to revision. The thinkers Wilber drew from remain valuable resources, but perhaps they are best engaged directly rather than through the filter of a totalizing system.

For practitioners and scholars, the lesson may be to cultivate the capacity to move fluidly between different theoretical frameworks, recognizing that each thinker Wilber drew from offers unique insights that can’t be fully captured in any synthesis. The map is not the territory, and the richness of human consciousness and development exceeds any attempt to fully systematize it.

Bibliography

Bauwens, M., & Kostakis, V. (2014). From the communism of capital to capital for the commons: Towards an open co-operativism. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 12(1), 356-361.

Beck, D. E., & Cowan, C. (2005). Spiral dynamics: Mastering values, leadership and change. Blackwell Publishing.

Bhaskar, R. (2008). A realist theory of science. Routledge.

Combs, A. (2009). Consciousness explained better: Towards an integral understanding of the multifaceted nature of consciousness. Paragon House.

Cook-Greuter, S. R. (2000). Mature ego development: A gateway to ego transcendence? Journal of Adult Development, 7(4), 227-240. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009511411421

Cortright, B. (2007). Integral psychology: Yoga, growth, and opening the heart. SUNY Press.

Crittenden, J. (2015). What is the meaning of “integral”? In S. Esbjörn-Hargens & M. E. Zimmerman (Eds.), Integral ecology: Uniting multiple perspectives on the natural world (pp. 23-51). Integral Books.

Edwards, M. G. (2010). Organizational transformation for sustainability: An integral metatheory. Routledge.

Esbjörn-Hargens, S. (2010). An overview of integral theory: An all-inclusive framework for the 21st century. Integral Institute Resource Paper, 1(1), 1-24.

Esbjörn-Hargens, S., & Zimmerman, M. E. (2009). Integral ecology: Uniting multiple perspectives on the natural world. Integral Books.

Ferrer, J. N. (2002). Revisioning transpersonal theory: A participatory vision of human spirituality. SUNY Press.

Forman, M. D., & Esbjörn-Hargens, S. (2013). The academic emergence of integral theory: Reflections on and clarifications of the 1st biennial integral theory conference. Journal of Integral Theory and Practice, 8(1&2), 123-143.

Fuhs, C. (2010). Towards a vision of integral leadership: A quadrivial analysis of eight leadership theories. Journal of Integral Theory and Practice, 5(1), 103-126.

Gidley, J. M. (2007). The evolution of consciousness as a planetary imperative: An integration of integral views. Integral Review, 5, 4-226.

Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action, Volume 1: Reason and the rationalization of society. Beacon Press.

Hargens, S. E. (2001). Integral psychology: Consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 33(2), 163-176.

Heron, J. (1992). Feeling and personhood: Psychology in another key. Sage Publications.

Hochachka, G. (2005). Developing sustainability, developing the self: An integral approach to international and community development. University of Victoria.

Ingersoll, R. E., & Cook-Greuter, S. (2007). The self-system in integral counseling. Counseling and Values, 51(3), 193-208. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007X.2007.tb00077.x

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development. Harvard University Press.

Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Harvard University Press.

Koestler, A. (1967). The ghost in the machine. Macmillan.

Küpers, W. (2011). Integral responsibilities for a responsive and sustainable practice in organization and management. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 18(3), 137-150. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.272

Laloux, F. (2014). Reinventing organizations: A guide to creating organizations inspired by the next stage of human consciousness. Nelson Parker.

Lancaster, B. L. (2004). Approaches to consciousness: The marriage of science and mysticism. Palgrave Macmillan.

Loevinger, J. (1976). Ego development: Conceptions and theories. Jossey-Bass.

Marshall, P. (2016). Mystical encounters with the natural world: Experiences and explanations. Oxford University Press.

McIntosh, S. (2007). Integral consciousness and the future of evolution. Paragon House.

Murray, T. (2009). What is the integral in integral education? From progressive pedagogy to integral pedagogy. Integral Review, 5(1), 96-134.

Nixon, G. (2010). Myth and mind: The origin of human consciousness in the discovery of the sacred. Journal of Consciousness Exploration & Research, 1(3), 289-337.

O’Fallon, T. (2015). Stages of consciousness: Current research and new perspectives. In O. Gunnlaugson & M. Brabant (Eds.), Cohering the integral we-space: Engaging collective emergence, wisdom and healing in groups (pp. 97-122). Integral Publishing House.

Paulson, D. S. (2008). Wilber’s integral philosophy: A summary and critique. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 48(3), 364-388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167807307828

Rentschler, M. (2006). AQAL glossary. Journal of Integral Theory and Practice, 1(3), 1-39.

Reynolds, B. (2004). Embracing reality: The integral vision of Ken Wilber. Tarcher/Penguin.

Rothberg, D. (1998). Ken Wilber and the future of transpersonal inquiry: A spectrum of views. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 30(1), 1-24.

Roy, B. (2006). A process model of integral theory. Integral Review, 3, 118-152.

Schwartz, M. (2010). Frames of AQAL: Integral critical theory and the emerging integral arts. Journal of Integral Theory and Practice, 5(1), 1-20.

Snow, K. C. (2007). The application of Ken Wilber’s integral model in early childhood education. ReVision, 29(3), 11-17. https://doi.org/10.3200/REVN.29.3.11-17

Stein, Z. (2012). On the use of the term integral: Vision-logic, meta-theory, and the growth-to-goodness assumptions. Journal of Integral Theory and Practice, 7(4), 95-113.

Taylor, E. I. (2010). William James and the humanistic implications of the neuroscience revolution: An outrageous hypothesis. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 50(4), 410-429. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167810376305

Torbert, W. R. (2004). Action inquiry: The secret of timely and transforming leadership. Berrett-Koehler.

Visser, F. (2003). Ken Wilber: Thought as passion. SUNY Press.

Washburn, M. (1995). The ego and the dynamic ground: A transpersonal theory of human development (2nd ed.). SUNY Press.

Wilber, K. (1977). The spectrum of consciousness. Quest Books.

Wilber, K. (1980). The Atman project: A transpersonal view of human development. Quest Books.

Wilber, K. (1981). Up from Eden: A transpersonal view of human evolution. Anchor Press/Doubleday.

Wilber, K. (1995). Sex, ecology, spirituality: The spirit of evolution. Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (1997). The eye of spirit: An integral vision for a world gone slightly mad. Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (2000a). Integral psychology: Consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (2000b). A theory of everything: An integral vision for business, politics, science, and spirituality. Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (2006). Integral spirituality: A startling new role for religion in the modern and postmodern world. Integral Books.

Wilber, K., Engler, J., & Brown, D. P. (1986). Transformations of consciousness: Conventional and contemplative perspectives on development. Shambhala.

Further Reading and Resources

Academic Critiques and Responses

The Journal of Consciousness Studies – Features ongoing debates about consciousness models including integral approaches

Integral Review – A transdisciplinary and transcultural journal for new thought, research, and praxis

SUNY Series in Transpersonal and Humanistic Psychology – Academic series including critiques of integral theory

Clinical and Therapeutic Applications

American Psychological Association – Integrative Approaches – Evidence-based integrative therapy resources

International Association for Analytical Psychology – Resources on depth psychology and developmental approaches

Hakomi Institute – Body-centered, somatic approach to therapy

The Trauma Research Foundation – Research on developmental trauma and treatment

Developmental Psychology Resources

Society for Research in Child Development – Latest research on human development

Harvard Graduate School of Education – Multiple Intelligences – Howard Gardner’s work on multiple intelligences

Center for Mindfulness – UMass Medical School – Research on mindfulness and consciousness

Contemporary Integrative Frameworks

The Institute for Integrative Health – Modern approaches to holistic health

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health – NIH research on integrative approaches

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Systems Theory – Contemporary systems thinking

Critical Philosophy and Theory

Continental Philosophy Review – Critical perspectives on grand theories

Theory, Culture & Society – Interdisciplinary exploration of contemporary thought

Philosophy Compass – Contemporary debates in philosophy of mind

Professional Development and Training

International Centre for Coaching and Mentoring Excellence – Evidence-based coaching methodologies

International Expressive Arts Therapy Association – Integrative expressive therapies

Somatic Experiencing International – Trauma resolution approaches

Research Databases and Journals

PubMed Central – Free full-text archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature

PsycINFO Database – Behavioral science and mental health literature

Google Scholar – Broad academic search engine

ResearchGate – Network for researchers to share papers

0 Comments