Executive Summary: Why Depth Psychology Heals Trauma

The Core Conflict: Standard talk therapy (CBT) often fails with complex trauma because it engages the Prefrontal Cortex (logic), while trauma lives in the Limbic System (emotion) and Brain Stem (body).

The Jungian Solution: Depth Psychology accesses these subcortical regions through symbol, image, and sensation. By bypassing the logical mind, we can:

- Reintegrate “Parts”: Using concepts like the Shadow and Inner Child to resolve fragmentation (Dissociation).

- Engage the Body: Recognizing emotions as somatic events, not just mental ones.

- Restore Meaning: Using the Hero’s Journey to reframe suffering as an initiation into a larger life.

Key Concepts: The Shadow, Archetypes, Active Imagination, The Monomyth.

6 Reasons You Should Use Jungian Techniques With Trauma Patients: A Somatic and Depth Approach

Trauma is not just a bad memory; it is a systemic failure of integration. When a person experiences a catastrophic event, the psyche fractures to survive. While traditional medical models focus on symptom reduction, they often fail to address the underlying fragmentation of the self.

This is where Jungian Depth Psychology excels. By focusing on the unconscious, the symbolic, and the somatic, Jungian techniques offer a roadmap for “re-membering” the dismembered self. Below are six compelling reasons why modern trauma therapists should integrate these century-old insights with cutting-edge neuroscience.

1. The Unconscious Controls the Nervous System

Jungian psychology posits that the unconscious world limits our conscious life. In trauma, this is literally true.

A major life trauma that has not been processed wraps its tentacles around a patient’s psyche without their awareness. The amygdala, the brain’s alarm system, cannot tell time. When a trigger occurs, the patient isn’t remembering the past; they are reliving it.

The Clinical Implication: Cognitive therapies ask patients to “think differently” about safety. However, the patient’s unconscious body knows it is unsafe. Jungian therapy respects the unconscious as a reality that must be negotiated with, not overridden. By bringing these unconscious complexes (or “triggers”) into the light, we stop them from operating as autonomous sub-personalities.

2. Archetypes are Somatic Maps (The Parts of the Body)

Jung described Archetypes as universal patterns of behavior. Modern neuroscience reveals that these patterns are also somatic—they live in the body.

Trauma disrupts our relationship with these archetypal energies.

The Warrior Archetype and Anger

When patients present with rage or powerlessness, they are dealing with a wounded Warrior Archetype.

* The Somatic Location: Most people store Warrior energy in the chest, lungs, or jaw.

* The Intervention: I have trauma patients imagine putting on “armor.” Children might visualize a halo or a superhero cape; adults might visualize medieval plate or cowboy gear.

* The Result: As they “wear” this archetype, their posture changes. They breathe deeper. They feel protected. This is Somatic Experiencing via Jungian imagery. It allows the patient to feel power without danger.

3. Internal Family Systems is Neo-Jungian (The Parts of the Mind)

Modern modalities like Internal Family Systems (IFS) and Voice Dialogue are essentially applied Jungian psychology. They deconstruct the psyche into “Parts” (sub-personalities).

One of the most common parts is the Inner Critic. This voice analyzes our every move, often mimicking the tone of a critical caregiver.

* In Trauma: The Critic becomes a tyrant. It attacks the self preemptively so that no one else can hurt us. It is a misguided protector.

* The Jungian Fix: Instead of fighting the critic, we interview it. “What are you trying to protect me from?” By personifying these parts, we turn the internal war into a democracy. We help the patient realize, “I am not my anxiety; anxiety is a part of me.”

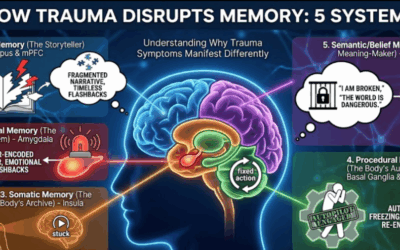

4. Imagination is the Language of the Right Brain

Trauma is stored in the right hemisphere of the brain—the side responsible for images, emotions, and sensations. It is often inaccessible to the language centers of the left brain. Therefore, you cannot “talk” someone out of trauma; you must “imagine” them out of it.

Active Imagination: Jung’s technique of Active Imagination allows patients to interact with their trauma symbols.

* Example: A patient feels a “heaviness” in their chest. We ask, “If that heaviness had a shape or a color, what would it be?”

* The Shift: The patient says, “It’s a black stone.” Now we have an object. We can ask, “Can we move the stone? Can we melt it?”

This bridges the gap between the frozen right brain and the creative left brain, facilitating the same processing found in EMDR.

5. Making Meaning (The Myth of the Self)

Trauma steals meaning. It shatters the narrative that the world is safe or that we are good people. Even after symptoms subside, a patient may feel hollow.

Jungian therapy differs from the medical model here. The medical model asks, “How do we fix the engine?” Jung asks, “Where is the boat going?”

We must help patients find their Personal Myth. Why did this happen? What initiation is this suffering forcing me to undergo?

* The Shift: Moving from “I am a victim of X” to “I am a survivor who learned Y.” This narrative restructuring is essential for Post-Traumatic Growth.

6. The Hero’s Journey (The Blueprint for Recovery)

Joseph Campbell, deeply influenced by Jung, identified the Monomyth or Hero’s Journey. This is not just a structure for movies; it is a structure for therapy.

The Stages of Trauma Recovery as a Journey:

1. The Call to Adventure: The crisis or trauma that shatters the ordinary world.

2. The Descent: The dark night of the soul, facing the monsters (Shadow work).

3. The Return: Integrating the trauma and returning to the world with new wisdom (The Elixir).

Trauma patients often feel stuck in the “Belly of the Whale.” They need to know that they are not just suffering pointlessly; they are in the middle of a story. Framing their struggle as a heroic descent gives them the dignity and courage required to face the Shadow.

Conclusion: The Sailboat vs. The Motorboat

Most manualized therapies are like fixing a motorboat—identifying the broken part and replacing it. Jungian therapy is like stitching the torn sail of a sailboat. We cannot control the wind (life), but we can repair the vessel so it can harness the wind to go somewhere new. For the trauma survivor, this restoration of agency and meaning is everything.

Bibliography

- Jung, C.G. (1991). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Routledge.

- van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Books.

- Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma. North Atlantic Books.

- Campbell, J. (2008). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New World Library.

Further Reading

- Hollis, J. (1998). The Eden Project: In Search of the Magical Other. Inner City Books.

- Hillman, J. (1975). Re-Visioning Psychology. Harper & Row.

- Ogden, P., & Fisher, J. (2015). Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment. W.W. Norton & Company.

0 Comments