A deep exploration of the questions that keep neuroscientists, evolutionary biologists, and psychologists awake at night—and why the answers remain tantalizingly out of reach.

The Known Unknowns of Human Experience

We live in an age of unprecedented scientific achievement. We have sequenced the human genome, imaged the brain in real-time, and developed artificial intelligences that can defeat grandmasters at chess. Yet for all this progress, some of the most fundamental questions about human experience remain stubbornly unanswered. Why do we dream? Why do we cry? Why does time seem to accelerate as we age? These are not merely philosophical curiosities—they are scientific mysteries that reveal the profound gaps in our understanding of what it means to be human.

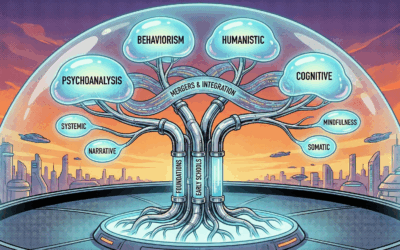

What follows is an exploration of fifty such mysteries, organized across the domains of evolution, cognition, psychology, and perception. For each, I will present the leading theories that researchers have proposed, introduce an additional perspective that cuts across multiple phenomena, and then consider how these explanations might work together—while acknowledging the mysterious variable that continues to elude even our most sophisticated investigations.

As a clinician who works daily with the complexities of human consciousness, I find these mysteries not frustrating but humbling. They remind us that the mind we use to understand the world remains, in many ways, opaque to itself. The questions that follow are invitations to wonder.

Part I: Evolutionary and Biological Mysteries

Why Do We Have Fingerprints?

Place your fingertip against a smooth surface and consider something counterintuitive: from a pure physics standpoint, smooth skin would actually provide better grip than ridged skin. The coefficient of friction between two smooth surfaces exceeds that between a textured surface and a smooth one. So why did evolution give us these intricate whorls and loops that we carry from birth to death, unique to each individual among the billions who have ever lived?

The first compelling theory focuses on tactile sensitivity. Research published in the journal Science has demonstrated that fingerprint ridges amplify vibrations when we run our fingers across textured surfaces, potentially increasing our sensitivity to fine details by as much as one hundred times. The ridges act as tiny resonating structures, converting texture information into neural signals with remarkable precision. This would explain why we can distinguish silk from satin with a single touch.

A second theory proposes that fingerprints function like tire treads, channeling water away from the contact surface to maintain grip in wet conditions. While smooth skin might provide superior friction on dry surfaces, our ancestors frequently encountered moisture—from rain, from handling wet plants and animals, from their own perspiration. The ridges create channels that allow water to escape, preventing the hydroplaning effect that would otherwise compromise our grasp.

The third major hypothesis concerns skin mechanics. Fingerprint ridges may allow the skin to stretch, compress, and conform to objects without tearing or blistering. The corrugated structure distributes mechanical stress more evenly than smooth skin would, protecting against the repetitive strain injuries that would otherwise accompany a lifetime of manual manipulation.

An additional theory worth considering involves thermoregulation and moisture management. The ridges increase surface area and may help regulate the temperature and moisture content of the fingertips, maintaining optimal conditions for both grip and sensitivity. This would explain why fingerprints are concentrated on the palmar surfaces—the very areas that make the most contact with objects and environment.

These theories likely work in concert. Evolution rarely optimizes for a single function when it can achieve multiple benefits simultaneously. The fingerprint ridge may have emerged initially for one purpose—perhaps tactile sensitivity in our arboreal ancestors—and subsequently proved advantageous for grip regulation, skin protection, and thermal management. The elegant efficiency of this multi-purpose adaptation speaks to the depth of evolutionary time.

Yet a mysterious variable persists. Why are fingerprints unique to each individual? No two fingerprints are identical, not even between identical twins who share the same genome. The patterns are influenced by the precise conditions in the womb during the weeks when ridges form—the pressure of amniotic fluid, the position of the fetus, random variations in cell division. This individual uniqueness serves no apparent evolutionary purpose; it appears to be an emergent property of developmental complexity rather than an adaptation. The question of why biology produces such elaborate individuality in a feature that would function identically if standardized remains unexplained.

Why Do We Dream?

We spend approximately one-third of our lives asleep, and within that sleeping third, we dream for roughly two hours each night. By the time you reach old age, you will have spent perhaps six years in the dream state. Despite this enormous investment of time and biological resources, the question of why we dream remains one of neuroscience’s most contentious debates. Is dreaming essential maintenance for the mind, or merely neural noise—the static produced by a brain idling through the night?

The memory consolidation theory, supported by extensive research at institutions including Harvard Medical School and documented in the Journal of Neuroscience, proposes that dreams are the subjective experience of the brain filing away the day’s events into long-term storage. During REM sleep, the hippocampus—the brain’s memory processing center—replays recent experiences, strengthening important connections and pruning irrelevant ones. Dreams, in this view, are what it feels like from the inside when your brain organizes its filing cabinet.

The threat simulation theory, developed by Finnish psychologist Antti Revonsuo, offers a more dramatic interpretation. Dreams evolved as a kind of virtual reality training ground where our ancestors could practice surviving dangerous situations without actual risk. The prevalence of threat-related content in dreams—being chased, falling, facing examinations unprepared—supports this view. Those who rehearsed survival scenarios in their sleep may have reacted more effectively when facing real threats during waking hours.

The activation-synthesis hypothesis, proposed by Harvard psychiatrists J. Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley, takes a more deflationary position. According to this theory, dreams are essentially meaningless—the brain’s attempt to construct a narrative from random neural firings during sleep. The brainstem generates essentially random signals; the cortex, doing what it always does, tries to make sense of them by weaving them into stories. Dreams feel meaningful because meaning-making is what brains do, not because the dreams themselves carry messages.

An additional theory deserving attention is the emotional regulation hypothesis. Research at the University of California, Berkeley has demonstrated that REM sleep helps process emotional experiences, reducing the emotional charge associated with difficult memories. Dreams may function as a form of overnight therapy, allowing us to confront and work through emotionally challenging material in a neurochemically altered state where stress hormones are suppressed.

A synthesis of these theories might propose that dreams serve multiple functions simultaneously—consolidating declarative memories, rehearsing survival responses, integrating emotional experiences, and maintaining neural health through activation patterns. The brain, ever efficient, may use the sleeping hours to accomplish several maintenance tasks at once, with dreams as the experiential byproduct.

Yet the mysterious variable here concerns the content of dreams. If dreams were purely functional—memory consolidation, threat rehearsal, emotional processing—why do they take narrative form at all? Why the elaborate scenarios, the strange characters, the impossible physics? Why does the dreaming mind create what feels like an alternate world rather than simply running maintenance routines in the background? The experiential richness of dreams—their capacity to feel as vivid as waking life—remains unexplained by purely functional accounts.

Why Do We Kiss?

Consider the act objectively: two individuals press their oral mucous membranes together, exchanging approximately 80 million bacteria in a ten-second kiss according to research published in the journal Microbiome. From an evolutionary standpoint, this is an excellent way to transmit disease. Yet kissing appears across virtually all human cultures and has been documented for at least 4,500 years. What could possibly explain the universality of this strange behavior?

The feeding ritual hypothesis traces kissing back to premastication—the ancient practice where mothers chewed food and passed it to their infants mouth-to-mouth. This behavior, still observed in some traditional cultures and common among our primate relatives, would have created powerful associations between oral contact, nourishment, and maternal bonding. Adult kissing, in this view, is an echo of our earliest experiences of love and sustenance.

The sniff test theory proposes that kissing evolved to allow potential mates to assess each other’s Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) genes—a crucial component of the immune system. Research has demonstrated that people are attracted to the scent of those with MHC profiles different from their own, presumably because offspring with diverse immune genetics would be better protected against disease. Kissing brings us close enough to unconsciously evaluate a partner’s genetic compatibility through chemosensory cues.

The germ sampling hypothesis takes a more direct immunological approach. When a woman kisses her partner, she is introduced to his microbial flora, including any pathogens he may carry. This early exposure triggers immune responses that may protect both her and any subsequent pregnancy. Studies have shown that women who are exposed to their partner’s microbiome before conception have reduced rates of preeclampsia and other pregnancy complications.

An additional theory worth integrating concerns attachment neurochemistry. Kissing triggers the release of oxytocin (the bonding hormone), dopamine (the reward neurotransmitter), and serotonin (mood regulation). This neurochemical cascade creates powerful feelings of attachment and desire, reinforcing pair bonding. In this view, kissing is essentially a drug delivery system, flooding the brain with the chemicals that create love.

These theories coalesce into a picture of kissing as a multi-purpose behavior that serves mate assessment, immune preparation, attachment formation, and the activation of ancient nurturing circuits. The mouth, one of our most sensitive and intimate body parts, becomes a site where genetic, immunological, and emotional information is exchanged simultaneously.

Yet a mysterious variable remains. Why does kissing feel pleasurable rather than merely useful? If kissing evolved purely for information exchange and immune priming, it could accomplish these functions without the intense pleasure that accompanies it. The hedonic quality of kissing—the fact that it feels so remarkably good—suggests that something beyond pure functionality is at work. The relationship between biological function and subjective pleasure in intimate behaviors remains one of the deeper puzzles of human sexuality.

Why Do We Have Dominant Hands?

Most animals show no preference for using one limb over another—they are truly ambidextrous. Yet approximately 90 percent of humans are right-handed, a ratio that has remained remarkably stable across cultures and throughout recorded history. Archaeological evidence suggests this proportion held even among our prehistoric ancestors. Why did humanity pick a side, and why that particular side?

The fighting hypothesis addresses the persistence of left-handedness rather than its minority status. In physical combat, a left-handed fighter has a significant advantage against opponents accustomed to facing right-handers. This “surprise factor” would maintain left-handedness in the population at precisely the frequency we observe—common enough to persist genetically, rare enough to retain its tactical advantage. Studies of success rates in combat sports consistently show elevated performance among left-handed athletes.

The language lateralization theory locates handedness in the brain’s asymmetrical organization. In most humans, language processing is concentrated in the left hemisphere, which also controls the right side of the body. The theory proposes that as language became increasingly important for our ancestors—enabling tool-making instructions, social coordination, and cultural transmission—the hemisphere housing language also took responsibility for the fine motor control needed for tool use. Writing, knapping flint, and threading needles all require the same precision as speech production.

The mother-child position hypothesis takes an entirely different approach. Early human mothers, like most mammalian mothers, preferentially held infants on the left side of the body. This positioning placed the baby’s ear against the mother’s heartbeat, providing the soothing rhythm familiar from the womb. But holding a baby on the left leaves only the right hand free for other tasks—gathering food, defending against predators, manipulating tools. Over countless generations, the right hand became the primary instrument of action.

An additional theory involves developmental canalization—the tendency of development to proceed along well-worn pathways. Once handedness became associated with specific brain structures and genetic patterns, developmental processes may have become “canalized” toward right-handedness. Small random asymmetries in fetal development would be amplified by genetic and environmental factors that bias toward the established norm. In this view, right-handedness persists partly because development tends to conserve existing patterns.

A synthesis might propose that language lateralization provided the initial brain asymmetry, maternal carrying patterns reinforced right-hand dominance behaviorally, and frequency-dependent selection maintained the minority of left-handers through their combat advantages. The developmental system then stabilized around these interacting pressures.

The mysterious variable concerns individual variation. If handedness is genetically influenced and evolutionarily significant, why is it not absolute? Why do left-handers exist at all in such a strongly right-biased species? And why do some individuals show mixed or ambidextrous patterns? The genetics of handedness turn out to be remarkably complex—no single “handedness gene” has been identified—and the developmental processes that determine hand preference in any given individual remain poorly understood.

Why Do We Cry Emotional Tears?

Humans are the only animals known to shed tears in response to emotion. Other creatures produce tears to lubricate and protect the eye, but only we weep at weddings, funerals, and the endings of particularly affecting films. This profound uniqueness demands explanation. Why did evolution burden us—and only us—with this peculiar form of expression?

The handicap signal theory, drawing on evolutionary biology’s concept of costly signaling, proposes that tears function precisely because they create vulnerability. When we cry, our vision blurs, making us less capable of fighting or fleeing. This visible impairment signals to potential aggressors that we are not a threat, inhibiting violence. The tears say, in effect, “I am helpless—there is no need to attack me.” The costliness of the signal (impaired vision) makes it hard to fake, lending it credibility.

The chemical detox hypothesis focuses on the composition of emotional tears, which differs from tears produced by eye irritation. Emotional tears contain higher concentrations of stress hormones including cortisol and prolactin. According to this theory, crying literally flushes stress chemicals from the body, explaining why we often feel better after a good cry. The tears are not merely symbolic but biochemically therapeutic.

The social glue theory emphasizes tears as communication. Visible tears trigger empathy and caregiving behavior in observers far more effectively than vocal expressions of distress alone. In our highly social species, the ability to elicit support from others would have been tremendously valuable. Tears may have evolved as an honest signal of distress that mobilizes social support, strengthening the bonds that held early human communities together.

An additional theory worth considering is the emotional intensity regulation hypothesis. Crying may serve as a circuit breaker for overwhelming emotion, allowing the nervous system to discharge accumulated tension and return to baseline. The autonomic nervous system response involved in crying—the deep breathing, the release of muscular tension—may actively shift the body from sympathetic (fight-or-flight) to parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) activation. In this view, tears are part of a broader emotional reset mechanism.

These theories can be synthesized into an integrated account where crying serves simultaneously as a vulnerability signal that inhibits aggression, a biochemical detoxification process that removes stress hormones, a social communication that elicits support, and a physiological reset mechanism that restores emotional equilibrium. The behavior’s persistence suggests it must provide substantial advantages across multiple domains.

Yet the mysterious variable involves the trigger specificity of tears. We cry at loss, yes, but also at beauty, at kindness, at reunion with loved ones, at profound music, at displays of moral courage. We cry at our children’s graduations. We cry at films about characters who never existed. This breadth of emotional triggers—encompassing both negative and positive valences—is difficult to explain by any single functional theory. What emotional tears signify at their deepest level, and why such disparate experiences can all produce them, remains one of psychology’s more poetic mysteries.

Why Do We Have Chins?

This question may seem trivial until you consider a remarkable fact: humans are the only primates with chins. Every other primate, including our closest relatives, has a face that slopes backward from the teeth. Only in humans does the mandible extend forward to create the distinctive projection we call a chin. The feature appears in no other hominin species—not Neanderthals, not Homo erectus, not any of our evolutionary cousins. We alone have this strange protrusion, and no one knows why.

The sexual selection hypothesis proposes that prominent chins evolved as signals of mate quality. In males, a strong chin correlates with testosterone levels and may signal genetic fitness; in females, a smaller chin may signal femininity and youth. Through generations of mate selection favoring individuals with prominent chins, the feature became fixed in our species. Attractiveness, in this view, drove anatomy.

The mechanical stress theory offers a structural explanation. When we chew, the mandible experiences significant bending forces. The chin may have evolved as a buttress, strengthening the jaw against the stresses of mastication. However, this theory faces a challenge: our jaws are actually weaker than those of other primates, and we eat softer foods. If mechanical strength were the primary driver, we should have more robust jaws overall, not just projecting chins.

The spandrel theory, borrowing a concept from evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould, proposes that the chin serves no purpose at all. It is simply the leftover bone that remained when human faces became smaller over evolutionary time. As our skulls expanded to accommodate larger brains, our faces shortened, but the mandible did not shrink proportionally. The chin is what happens when a small face meets a normal-sized jaw. It is an accident of geometry, not an adaptation.

An additional theory involves speech production. The unique configuration of the human vocal tract—which enables our sophisticated language abilities—required restructuring of the face and jaw. The chin may be a byproduct of the anatomical changes that made human speech possible. The forward projection might help anchor the muscles involved in the precise articulation of language.

These theories might work together in a developmental cascade: changes in brain size altered facial structure, the resulting chin proved incidentally useful for speech-related musculature, and subsequently came under sexual selection pressure. What began as a geometrical accident may have become a target of aesthetic preference.

The mysterious variable is the timing and specificity of chin emergence. The chin appears suddenly in the fossil record with anatomically modern humans approximately 200,000 years ago. It is not present in transitional forms. This sudden appearance is difficult to explain by gradual selective processes. What developmental change produced the chin so rapidly, and why it affected only our lineage among all the hominins, remains an open question in paleoanthropology.

Why Do We Blush?

Charles Darwin called blushing “the most peculiar and most human of all expressions.” He was fascinated by its involuntary nature—we cannot blush at will—and by the apparent paradox it presents. Blushing reveals our embarrassment, our guilt, our shame. Why would evolution design a mechanism that broadcasts our discomfort to others? Why would we advertise the very states we most wish to conceal?

The apology signal theory proposes that blushing functions as a non-verbal, unfakeable apology. When we violate social norms—whether through error, transgression, or simply being caught in an awkward situation—the blush communicates that we recognize the violation and care about our standing in the group. This signal diffuses potential aggression and facilitates forgiveness. Studies have shown that people who blush after social transgressions are judged more favorably and forgiven more readily than those who do not.

The fight-or-flight misfire theory offers a more mechanical explanation. When we feel exposed or evaluated, the sympathetic nervous system activates. Blood flows to major muscle groups in preparation for action—but also, incidentally, to the face. The blush may be an accidental side effect of this arousal response, a physiological quirk rather than a functional adaptation. We blush for the same reason we sweat when nervous: the body is preparing for a threat that social embarrassment mimics but does not actually pose.

The honesty indicator theory emphasizes what blushing reveals about character. Because blushing cannot be voluntarily controlled, it serves as proof that the blusher possesses normal social emotions—guilt, shame, embarrassment, concern for others’ opinions. The blush essentially certifies that you are not a sociopath. Those who cannot blush (as is the case in certain antisocial personality disorders) lose access to this credibility signal, making others less likely to trust them.

An additional theory involves group cohesion maintenance. Blushing may have evolved to maintain social equilibrium by signaling submission or appeasement after status challenges or social mistakes. In hierarchical social groups—which all human societies are to varying degrees—such signals would reduce conflict and maintain group cooperation. The blush signals, “I acknowledge my place; please don’t exclude me.”

These perspectives synthesize into a picture of blushing as a multi-function social tool: an automatic apology that cannot be faked, an honest signal of normal conscience, and a submission display that maintains group harmony. The involuntary nature that makes blushing embarrassing is precisely what makes it credible and socially valuable.

The mysterious variable concerns the mechanism of facial specificity. Why the face? The sympathetic nervous system affects blood vessels throughout the body, yet blushing is confined to the face, neck, and upper chest—the regions most visible in social interaction. This specificity suggests some adaptive design, yet the neural pathways that produce this localized response are not well understood. How the brain learned to route embarrassment specifically to the face remains unclear.

Why Do We Yawn?

You may yawn while reading this sentence. The mere mention of yawning triggers yawning—a phenomenon called contagious yawning that occurs even when we watch someone yawn on video, read about yawning, or simply think about it. We yawn when tired, but also when bored, stressed, or preparing for activity. We cannot easily suppress yawns once they begin. What is this strange behavior, and why is it so contagious?

The brain cooling theory, supported by research at Princeton University, proposes that yawning functions as a thermoregulatory mechanism. The deep inhalation brings cool air into the nasal and oral cavities, while the stretching of the jaw increases blood flow to the head. Together, these actions cool the brain—essentially functioning as a biological fan for an organ that generates significant heat and performs poorly at elevated temperatures. This would explain why we yawn more in warm conditions and less when we apply cold compresses to the forehead.

The state change theory focuses on the physiological mechanics of yawning. The deep stretch of the lungs, the expansion of the rib cage, the tensing of the jaw muscles—these actions may prepare the body for transitions between states of arousal. We yawn when waking to stretch the respiratory system into alertness; we yawn when tired to signal the body’s readiness for sleep. The yawn functions as a physiological gear shift, helping the body transition between activity and rest.

The empathy signal theory addresses the contagious quality of yawning. Studies have shown that contagious yawning correlates with measures of empathy—psychopaths show reduced contagious yawning, as do individuals with autism spectrum disorders that affect social cognition. The spread of yawning through a group may have served to coordinate sleep schedules among our ancestors, ensuring that the tribe slept and woke together. The more attuned you are to others, the more susceptible you are to their yawns.

An additional theory involves arousal regulation. Yawning may function to optimize alertness—not simply to increase it, as often assumed, but to regulate it. We yawn both when under-aroused (bored, sleepy) and when over-aroused (anxious, before performances). The yawn may be a homeostatic mechanism that pushes arousal levels toward an optimal middle range.

These theories integrate into a comprehensive picture: yawning regulates brain temperature, signals state transitions, coordinates group behavior through empathic contagion, and maintains optimal arousal levels. The behavior sits at the intersection of physiology, social cognition, and thermoregulation.

The mysterious variable is the precise trigger mechanism. What neural system detects the need for a yawn and initiates the behavior? Yawns occur across vertebrates—fish yawn, birds yawn, even fetuses yawn in the womb—suggesting an ancient and fundamental mechanism. Yet the neural circuitry that produces yawning, and that makes it so resistant to voluntary suppression, has not been fully mapped. Why yawning is so automatic, and why thinking about it is sufficient to trigger it, remains unexplained.

Why Are We Ticklish?

Tickling occupies a peculiar position in human experience. It produces laughter—typically a sign of pleasure—yet feels uncomfortably close to torture. We cannot tickle ourselves; the brain apparently cancels the response when it predicts the sensation. We are ticklish in specific locations (armpits, soles of feet, ribs, neck) that correspond to vulnerable body parts. This strange constellation of properties demands explanation.

The combat training theory proposes that ticklishness evolved to teach children to protect vulnerable areas during play fighting. When tickled in the ribs or neck, we reflexively curl up and protect those regions—the same areas that would be targeted by predators or enemies. The laughter encourages continued play while the defensive reflexes build motor patterns for actual combat. Tickle games may be early training for the serious business of survival.

The parasite detection theory focuses on the sensitivity aspect of ticklishness. The body regions where we are most ticklish are also regions where parasites—insects, spiders, ticks—might crawl unnoticed. Ticklishness may represent heightened sensitivity to light touch in these areas, helping us detect and remove creatures that might bite, sting, or burrow. The unpleasant quality of tickling would motivate immediate removal of the stimulus.

The social bonding theory emphasizes the role of tickling in parent-child and peer relationships. Tickle games require close physical contact, create shared laughter, and establish trust (the tickler must know when to stop). These interactions strengthen social bonds, particularly between caregivers and infants. The behavior’s presence in other primates supports this social interpretation—great apes engage in tickle-like play that produces vocalizations resembling laughter.

An additional theory concerns boundary negotiation. Tickling may serve as a safe context for practicing the negotiation of physical boundaries—when touch is welcome and when it becomes too much, how to signal discomfort, how to respect another’s limits. These skills would be crucial for social species where physical contact is both necessary and potentially threatening. Tickle games teach consent.

Synthesizing these theories, ticklishness emerges as a multifunctional adaptation serving defense training, parasite detection, social bonding, and boundary negotiation—all activated by a mechanism that distinguishes self-generated from other-generated touch.

The mysterious variable is the laughter itself. Why does tickling produce laughter when the experience is not straightforwardly pleasant? The laughter of tickling sounds similar to but is neurologically distinct from genuine amusement. Some researchers propose that tickle laughter is a submissive signal; others that it encourages the tickler to continue the socially valuable play. But why laughter specifically, rather than some other vocalization, accompanies this particular form of touch remains puzzling.

Why Do We Experience the Uncanny Valley?

In 1970, Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori described a strange phenomenon. As robots become more human-like, people respond to them more positively—until a threshold is crossed. When an artificial entity looks almost but not quite human, our response shifts from affinity to revulsion. Mori called this the “uncanny valley”—the dip in emotional response that occurs when artificial entities approach but do not quite achieve human appearance. The phenomenon has been confirmed repeatedly in research on robots, computer animation, prosthetics, and even cosmetically altered faces. What is it about the almost-human that disturbs us so profoundly?

The pathogen avoidance theory draws on evolutionary psychology’s concept of the behavioral immune system. Throughout human evolution, individuals who looked “wrong”—with asymmetrical features, unusual coloring, or abnormal movement patterns—were often carriers of disease. The uncanny valley response may be a pathogen-detection system, triggering avoidance of entities that display the subtle signs of illness or infection. An android that moves strangely resembles a person with a neurological disorder; a face that looks slightly off resembles a face disfigured by disease.

The mortality salience theory proposes that human-like entities that lack true life remind us of death. A robot that looks human but has dead eyes, or moves with mechanical precision, resembles a corpse—reanimated flesh from which life has departed. The uncanny valley may be triggered by unconscious associations with death, activating the existential terror that humans typically suppress. The almost-human forces us to confront human mortality.

The category confusion theory focuses on cognitive processing. The brain relies on rapid categorization—is this thing human or not human, alive or not alive, friend or threat? An entity that falls between categories creates processing difficulties. We cannot cleanly file the almost-human into either the “human” or “robot” category, and this cognitive failure produces discomfort. The uncanny valley is the feeling of categorical vertigo.

An additional theory involves social inference failure. We automatically attempt to read intentions, emotions, and mental states from faces and bodies—a process called mentalizing. An entity that looks human triggers these inference systems, but when the inferences fail (because there is no actual mind behind the face), we experience the uncanny valley as a social detection error. The almost-human tricks our social cognition and then reveals itself as empty.

These theories combine to suggest that the uncanny valley represents multiple detection systems firing simultaneously: pathogen avoidance, death anxiety, categorical confusion, and social inference failure all contribute to the characteristic revulsion response.

The mysterious variable is the precision of the threshold. Why is there a valley rather than a simple monotonic relationship? Why do we respond positively to clearly artificial entities (cartoon characters, stylized robots) but negatively to near-human ones? The precise features that trigger the uncanny response—and why very subtle deviations from human appearance are more disturbing than obvious ones—remain poorly understood.

Part II: Cognitive and Perceptual Mysteries

Why Do We See Fractals on Psychedelics?

Users of psychedelic substances—LSD, psilocybin, DMT—consistently report a specific class of visual experience: complex geometric patterns, spiraling fractals, lattice structures, and kaleidoscopic imagery. These patterns share remarkable commonalities across individuals, cultures, and specific substances. Why does altered brain chemistry produce these specific visual forms rather than random noise or completely idiosyncratic imagery?

The Turing mechanism theory draws on the mathematics of pattern formation. Alan Turing, better known for his work in computation, also developed mathematical models of how interacting chemicals can produce spontaneous patterns—stripes, spots, spirals—through reaction-diffusion dynamics. When psychedelics disrupt the normal inhibitory processes in the visual cortex, similar reaction-diffusion patterns may emerge in neural activity. The fractals people see may be the visual representation of mathematical patterns inherent to the brain’s structure.

The entropic brain theory, developed by researchers at Imperial College London, proposes that psychedelics increase the entropy (disorder) of brain activity. Under normal conditions, the brain operates in relatively constrained states; psychedelics release these constraints, allowing brain activity to explore a wider range of configurations. Fractal patterns may be visual representations of this information overload—the geometry of chaos made visible.

The network cross-talk theory focuses on altered connectivity. Neuroimaging studies show that psychedelics increase communication between brain regions that normally operate independently. The visual cortex may begin receiving input from regions that process mathematical relationships, spatial navigation, or pattern recognition. The fractals may be what happens when mathematical processing systems project directly into visual experience.

An additional theory concerns the revelation of neural architecture. The visual cortex is organized in hierarchical, self-similar layers—a structure that itself has fractal properties. Psychedelics may strip away the processed “content” of vision, revealing the underlying architecture of the visual system itself. When you see fractals on psychedelics, you may be seeing the shape of your own visual cortex.

These theories converge on the idea that psychedelic visuals are not random but reflect fundamental properties of brain organization—mathematical patterns inherent to neural dynamics, the geometry of disinhibited cortical activity, the architecture of visual processing itself.

The mysterious variable is the consistency of specific forms. Why do people across cultures report similar geometric motifs—spirals, tunnels, lattices, webs? This cross-cultural consistency, documented in anthropological studies of shamanic traditions and confirmed in laboratory research, suggests something universal about these patterns. Whether they reflect universal brain architecture, fundamental mathematical forms, or something deeper about the nature of consciousness remains an open question that reaches beyond neuroscience into philosophy and perhaps physics.

Why Do We Experience Déjà Vu?

You walk into a room you have never visited before, and suddenly you are gripped by the overwhelming sensation that you have lived this exact moment previously. The lighting, the arrangement of furniture, the conversation occurring around you—all of it feels not merely familiar but specifically remembered. Yet you know, with your rational mind, that this is impossible. You have never been here. This is déjà vu (literally “already seen”), and approximately two-thirds of people report having experienced it.

The dual processing delay theory proposes a timing glitch in perception. Information from our senses normally arrives at conscious awareness as a unified experience, but the different processing streams that construct this experience operate at slightly different speeds. If one eye, or one brain hemisphere, processes a scene milliseconds before the other, the second processing might arrive as a “memory” of something already seen—creating the illusion that the present moment is being remembered from the past.

The hologram theory (not to be confused with holographic universe theories) suggests that déjà vu occurs when some element of a present experience matches an element from an actual memory. A particular quality of light, a specific configuration of sounds, a familiar scent—any of these might trigger the pattern completion systems that normally reconstruct memories. The brain, primed by this partial match, floods the present moment with the feeling of recollection, even though the complete scene is novel.

The memory filing error theory proposes a sorting mistake. Normally, incoming experiences are processed first in short-term memory before being consolidated into long-term storage. Déjà vu may occur when an experience is erroneously routed directly to long-term memory, creating the sensation that something currently being experienced is being retrieved from the past. It is a filing error that creates the illusion of prior experience.

An additional theory involves temporal lobe activity. Déjà vu can be reliably induced by electrical stimulation of the temporal lobe, and it occurs frequently as an aura preceding temporal lobe seizures. This suggests that déjà vu may result from brief, transient abnormal activity in regions involved in memory and familiarity processing—a neural hiccup that generates the feeling of recollection independent of actual memory content.

Synthesizing these theories, déjà vu appears to arise from the brain’s memory systems misfiring—whether through timing delays, partial pattern matching, filing errors, or transient neural abnormalities—creating the subjective feeling of remembering without the corresponding actual memory.

The mysterious variable is the experiential specificity. Why does déjà vu feel so particular—not merely “this is familiar” but “I have lived precisely this moment before”? The phenomenon involves not just a sense of familiarity but a specific kind of temporal displacement, a feeling that time has somehow folded back on itself. Why memory errors would produce this specific quality of temporal experience, rather than simple vague familiarity, remains unexplained.

Why Do We Experience “The Call of the Void”?

You stand at the edge of a cliff, a balcony railing, a subway platform as the train approaches. Suddenly, unbidden and unwanted, a thought flashes through your mind: jump. You have no intention of jumping. You have no desire for self-harm. Yet the thought is vivid, insistent, and deeply disturbing. The French have a name for this: l’appel du vide—the call of the void. What explains this intrusive urge that affects people with no suicidal ideation whatsoever?

The misinterpreted safety signal theory offers a cognitive explanation. When you approach a dangerous height, your brain’s safety systems activate instantaneously, generating an immediate “back up!” command. This protective impulse arrives faster than conscious thought. Your conscious mind, receiving this jolt of alarm without clear context, interprets the physical sensation of recoil as evidence of an urge to jump. You experience your own safety mechanism as its opposite.

The Thanatos theory draws on Freud’s concept of the death drive—a hypothetical unconscious urge toward self-destruction that exists in tension with Eros, the life drive. In this psychoanalytic framework, the call of the void represents the momentary surfacing of an ever-present but normally suppressed drive toward dissolution. The void calls because part of us, at the deepest level, wants to answer.

The anxiety sensitivity theory takes a more parsimonious approach. The call of the void may be a form of intrusive thought—the kind of unwanted mental content that anxious minds are particularly prone to generating and then taking seriously. When we approach heights, our anxiety system activates. Anxious minds generate “what if” scenarios. The jump thought is simply one such scenario that, because of its disturbing content, captures attention and feels significant. Research published in the Journal of Affective Disorders has found that the call of the void is more common in people with higher anxiety sensitivity but shows no correlation with actual suicidal ideation.

An additional theory concerns risk assessment simulation. The brain may automatically simulate potential actions to evaluate their consequences—a kind of mental modeling that helps us navigate complex environments. The “jump” simulation is the brain assessing the risk of the current situation by mentally modeling what would happen if we acted on the possibility. We experience the simulation as an urge because mental simulation and intention activate overlapping neural systems.

These theories combine to suggest that the call of the void represents a confusion between safety signals, risk simulations, and intrusive thoughts—the brain’s protective and predictive systems producing an experience that feels like dangerous desire but is actually something quite different.

The mysterious variable is the universality of the experience across cultures and individuals with no history of self-harm. If the call of the void were purely an anxiety phenomenon, we would expect it to correlate strongly with anxiety disorders—but it affects many people with no such history. If it were a misinterpreted safety signal, we would expect it to diminish with exposure—but experienced climbers and construction workers report it as well. What makes this particular intrusive thought so universal, and why it takes this specific form, remains unclear.

Why Do Songs Get Stuck in Our Heads?

You heard a fragment of a song—perhaps just the chorus, perhaps just a few bars—and now it plays in your mind on an endless loop. Hours pass, and still it persists. You try to think of other things, but the song keeps returning. This is an “earworm” (from the German Ohrwurm), and research suggests that over 90% of people experience them at least once a week. Why do our brains trap us in these musical loops?

The Zeigarnik effect theory draws on a well-established principle of memory. The Zeigarnik effect describes our tendency to remember incomplete tasks better than completed ones—the brain holds unfinished business in active memory, nagging us to resolve it. When we hear a song fragment without its resolution—the chorus without the verse, the buildup without the payoff—the brain may loop the material in an attempt to “complete” the musical thought. The earworm persists because it feels unfinished.

The cognitive itch theory proposes that certain melodic patterns create self-sustaining neural oscillations. Just as an itch creates a sensation that persists until scratched, certain musical structures—particular intervals, rhythms, or melodic contours—may create brain activity patterns that maintain themselves through feedback loops. The earworm is a kind of neural hiccup, a rhythm that the brain has difficulty stopping once it starts.

The mood regulation theory suggests that earworms serve an emotional function. Research has shown that earworm songs often match the listener’s current mood or energy level. The brain may select and loop music that maintains a desired emotional state—upbeat songs to sustain energy, melancholy songs to process sadness. The earworm is not a bug but a feature of emotional self-regulation.

An additional theory involves memory consolidation. Repetitive mental rehearsal is one of the brain’s primary mechanisms for strengthening memories. Earworms may represent the brain practicing and encoding musical material—the same process that helps us learn, applied to music we may not consciously want to memorize. The loop persists because the brain is actively working to make the memory permanent.

These theories together suggest that earworms arise from the intersection of incomplete task processing, self-sustaining neural patterns, emotional regulation needs, and memory consolidation mechanisms. The simple experience of a song stuck in your head reflects complex interactions among multiple cognitive systems.

The mysterious variable is the selection process. Why that song and not another? Of all the music you have heard, why does your brain loop this particular fragment? Research has identified some properties of earworm-prone songs (simple melodies, unexpected intervals, familiar structures), but these properties do not fully predict which songs will become earworms for which individuals. The personalization of earworm selection—why your brain chooses your particular mental soundtrack—remains poorly understood.

Why Does Time Speed Up as We Age?

Ask any adult, and they will confirm it: childhood summers lasted forever, but adult years flash by in what feels like months. This subjective acceleration of time is one of the most universal experiences of aging, reported across cultures and confirmed by psychological research. Yet objectively, time passes at the same rate. What accounts for this distortion in temporal experience?

The proportional theory offers a mathematical explanation. When you are five years old, one year represents twenty percent of your entire life—a vast proportion of your existence. When you are fifty, that same year represents only two percent—a comparatively tiny fraction. Each successive year becomes proportionally smaller relative to your total experience, creating the sensation that time is accelerating even though the absolute duration remains constant.

The holiday paradox theory focuses on memory formation. We do not actually experience time directly; we reconstruct our sense of duration from memories. When we are young, everything is novel—new experiences, new places, new people, new knowledge. This novelty creates dense memory encoding. In retrospect, periods rich in memories seem long because there is much to remember. As adults settle into routines, novelty diminishes. Fewer new memories are formed, so looking back, the time seems “empty” and therefore short. A vacation feels long while it’s happening (novel experiences) but short in retrospect (few memories compared to months of routine).

The processing speed theory takes a neurological approach. Research suggests that the brain’s processing speed declines with age—neurons fire more slowly, processing takes more time. When we are young, our brains take more “frames per second,” creating richer temporal resolution. More perceptual moments per minute means time feels stretched. As processing slows, we experience fewer perceptual moments per unit of objective time, compressing subjective experience.

An additional theory concerns attention and engagement. When we are fully absorbed in an activity—the state psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi called “flow”—time seems to vanish. When we are bored or merely going through motions, we notice time passing and it drags. Children, encountering the world fresh, may be more often in states of absorbed engagement. Adults, managing responsibilities and routines, may be more often in states of clock-watching tedium. The cumulative effect is that adult time seems faster.

These theories synthesize into a picture where temporal acceleration results from proportional diminishment, reduced novelty and memory formation, slowed neural processing, and changes in attentional engagement. Each mechanism contributes to the common experience of accelerating time.

The mysterious variable is individual variation. Some adults report that time has not accelerated for them; others feel the acceleration intensely. What accounts for these differences? Preliminary research suggests that lifestyle factors—the extent to which one continues to seek novelty, maintain engagement, and create rich memories—may influence subjective temporal experience. But why some individuals seem naturally resistant to temporal acceleration, and whether this resistance can be cultivated, remains an open question with profound implications for how we experience our finite years.

Why Do We Have Tip-of-the-Tongue States?

You know the word. You can describe what it means. You can recall its first letter, perhaps even how many syllables it has. You can sense its shape, its rhythm, the way it would feel to say it. But you cannot retrieve it. It hovers just at the edge of conscious access, tantalizingly close yet persistently out of reach. This is the “tip-of-the-tongue” (TOT) state, and it reveals something profound about how memory is organized in the brain.

The blocking theory proposes that TOT states occur when a similar but incorrect word occupies the retrieval pathway. When you search for “archipelago,” your brain might retrieve “peninsula” instead. This competitor blocks access to the target word, holding the pathway hostage until the interloper is cleared. The more you try to retrieve the blocked word, the more the blocker strengthens its hold. Sometimes the only solution is to stop trying and let the blocking word fade.

The incomplete activation theory offers a structural explanation. Words are stored in networks that encode different types of information separately—meaning (semantics), sound (phonology), spelling (orthography). A TOT state occurs when the semantic component of a word is fully activated, but the phonological component has not achieved the threshold needed for conscious access. You know what the word means because meaning is available, but you cannot say it because sound is not. The experience of “knowing without being able to say” reflects the partial activation of a distributed memory network.

The retrieval failure theory focuses on the retrieval process itself rather than stored representation. The word is stored correctly and completely, but the retrieval cue is insufficient to access it. Like searching for a file on a computer with the wrong search terms, the brain cannot locate the word not because anything is wrong with the word’s storage, but because the current query is inadequate. The TOT state occurs in the gap between knowing a word exists and finding the pathway to reach it.

An additional theory concerns cognitive resource depletion. TOT states are more common when we are tired, stressed, or multitasking—conditions that deplete the attentional resources needed for memory retrieval. The word may be accessible under optimal conditions, but in states of resource depletion, retrieval mechanisms cannot summon enough activation energy to complete the process. The TOT state is a kind of cognitive “low battery” warning.

These theories together depict TOT states as arising from blocking by competitors, incomplete network activation, suboptimal retrieval cues, or resource depletion—all variations on the theme of almost-but-not-quite-successful memory retrieval.

The mysterious variable is the feeling of knowing itself. How do we know that we know a word without being able to produce it? This metacognitive awareness—knowing about our own knowledge—seems to require access to the word in some form, yet we clearly do not have access sufficient to produce it. The phenomenology of the TOT state—that peculiar sense of hovering presence—implies that we can detect memory content without fully retrieving it, through some mechanism that remains poorly understood.

Part III: Psychological and Social Mysteries

Why Do We Procrastinate?

You have a deadline. You know the work must be done. You know that delaying will create stress, compromise quality, and possibly carry real consequences. Yet here you are, checking social media, reorganizing your desk, reading articles about procrastination instead of doing the task at hand. This self-defeating behavior affects virtually everyone to some degree and costs billions in lost productivity annually. Why do we do it?

The mood repair theory, developed by researchers at Carleton University, reframes procrastination not as laziness or poor time management but as emotion regulation. When we face a task that evokes negative emotions—anxiety, boredom, frustration, self-doubt—procrastination offers immediate emotional relief. We avoid the task to avoid the feeling. In this view, procrastination is a short-term mood repair strategy that prioritizes present relief over future consequences.

The temporal discounting theory draws on behavioral economics. Humans consistently value immediate rewards more than future rewards of equal or greater value—a phenomenon called hyperbolic discounting. The pleasure of relaxing now feels more real, more valuable, than the distant satisfaction of completed work. Our brains were not evolved for environments where long-term planning matters; they were evolved for immediate survival. Procrastination is ancestral psychology misapplied to modern challenges.

The fear of failure theory shifts focus from task avoidance to self-protection. If I don’t really try until the last minute, then poor results can be attributed to insufficient time rather than insufficient ability. Procrastination becomes a self-handicapping strategy, protecting self-esteem by providing an excuse for failure. The procrastinator’s logic: “I could have done better if I’d tried” is preferable to “I tried my best and failed.”

An additional theory concerns executive function impairment. Procrastination correlates strongly with difficulties in executive function—the cognitive processes responsible for planning, impulse control, and task initiation. For some individuals, procrastination is not primarily about emotion or motivation but about the neurological systems that translate intention into action. The task is not done not because it is avoided but because the bridge between wanting to do it and actually starting it is impaired.

These theories synthesize into a picture of procrastination as a complex behavior with multiple potential roots: emotion avoidance, temporal discounting, self-protection, and executive function difficulty. Different procrastinators may procrastinate for different reasons, and effective interventions must target the underlying cause.

The mysterious variable is the variability of procrastination within individuals. The same person may be highly productive on some tasks and desperately procrastinating on others that seem, objectively, no more difficult or aversive. What determines which tasks trigger procrastination and which do not? The task-specific nature of procrastination—why this task and not that one—remains poorly predicted by current theories.

Why Do We Experience Imposter Syndrome?

You have achieved success—perhaps significant success. You have the credentials, the awards, the position. Yet secretly, you are convinced that you do not truly deserve any of it. You are a fraud who has somehow fooled everyone, and at any moment you will be exposed. This is imposter syndrome, and research suggests it affects approximately 70% of people at some point in their lives, with particularly high prevalence among high achievers.

The pluralistic ignorance theory proposes that imposter syndrome arises from an information asymmetry. We have direct access to our own inner experience—the doubts, the struggles, the moments of confusion and inadequacy. But we only see others’ outer presentation—the confidence, the competence, the apparent ease. We compare our blooper reel to everyone else’s highlight reel. The conclusion is inevitable: they are legitimate; I am faking it.

The family dynamics theory locates imposter syndrome in developmental experience. In some families, a child is designated as “the smart one” or “the successful one”—a label that creates pressure to never struggle, never fail, never be seen learning. Any difficulty becomes evidence that the label was undeserved; any success becomes mere confirmation of external expectations rather than personal accomplishment. The imposter feeling begins in the family system and persists into adulthood.

The systemic bias theory expands the frame beyond individual psychology. Imposter syndrome is not distributed randomly across the population; it is more prevalent among people in environments that were not designed for them—women in male-dominated fields, people of color in predominantly white institutions, first-generation professionals in elite settings. The “imposter” feeling may be an accurate perception of genuine friction between the self and an unwelcoming environment, internalized as personal inadequacy rather than recognized as systemic barrier.

An additional theory concerns attribution patterns. Research on attribution shows that some individuals habitually attribute success to external factors (luck, help, easy circumstances) and failure to internal factors (lack of ability, personal flaws). This attribution style—the opposite of the self-serving bias that protects most people’s self-esteem—creates the cognitive conditions for imposter syndrome. Every success becomes a fluke; every struggle becomes proof of inadequacy.

These theories combine to depict imposter syndrome as arising from information asymmetry about others’ experiences, family patterns that pathologize normal struggle, systemic environments that create genuine friction, and attribution patterns that discount success while amplifying failure.

The mysterious variable is the resilience of the belief despite evidence. People with imposter syndrome often accumulate extensive evidence of legitimate competence—degrees, promotions, praise, accomplished projects—yet the belief in their fraudulence persists. Why does evidence not update the belief? What maintains the conviction of illegitimacy in the face of overwhelming contrary evidence? The epistemology of imposter syndrome—how it becomes immune to disconfirmation—remains poorly understood.

Why Do We Gossip?

Gossip is often condemned as petty, malicious, and morally dubious. Yet it is also universal across cultures, consuming by some estimates up to two-thirds of all human conversation. If gossip were simply a vice, we would expect significant cultural variation in its prevalence. Instead, it appears to be a species-typical behavior, as universal as language itself. What evolutionary function could such behavior serve?

The grooming hypothesis, developed by evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar, proposes that language—and specifically gossip—evolved as a substitute for physical grooming. In other primates, social bonds are maintained through picking through each other’s fur, a time-consuming activity that limits group size. Gossip allows humans to “groom” multiple individuals simultaneously through speech, enabling the large social groups that characterize human societies. Talking about others is verbal grooming—the social bonding behavior of a species too numerous for physical touch.

The policing mechanism theory frames gossip as a social control system. In groups where cooperation is essential but free-riding is tempting, reputation becomes a crucial incentive. Gossip spreads information about who cooperates and who defects, who can be trusted and who cannot. The threat of reputational damage through gossip enforces prosocial behavior; knowing that your actions will be discussed motivates conformity to group norms. Gossip is the enforcement arm of social morality.

The information warfare theory takes a more competitive view. In the mating and resource hierarchies that characterize social species, information is power. Gossip can be strategically deployed to damage rivals’ reputations, elevate one’s own status, and manipulate social alliances. From this perspective, gossip is not merely social but political—a tool for advancing individual interests in the complex game of social competition.

An additional theory concerns knowledge management. Social environments are informationally complex; we cannot directly observe everyone’s behavior. Gossip functions as a collective information-processing system, pooling observations across individuals to create shared knowledge about the social environment. Through gossip, we learn who is reliable, who is having difficulties, who has formed new alliances, who has broken old ones. The gossip network is the social brain of the group, distributed across its members.

These theories integrate into a picture of gossip as simultaneously bonding (verbal grooming), regulatory (norm enforcement), competitive (status manipulation), and informational (collective knowledge management). The same conversation can serve all these functions simultaneously.

The mysterious variable is the pleasure of gossip. If gossip served purely functional purposes, we would expect it to feel neutral—a tool like any other. Instead, gossip is often experienced as intrinsically enjoyable, even when we feel guilty about it. What makes talking about others so pleasurable? The hedonic quality of gossip—and why we often enjoy sharing negative information about others—remains unexplained by purely functional accounts.

Why Are We Altruistic?

A stranger collapses in the street, and people rush to help. A philanthropist donates their fortune to causes they will never benefit from. A soldier throws themselves on a grenade to save their comrades. From an evolutionary standpoint, these behaviors are deeply puzzling. Evolution favors traits that increase the survival and reproduction of the individual carrying them. How can altruism—behavior that benefits others at cost to oneself—possibly have evolved?

The kin selection theory, developed by evolutionary biologist W.D. Hamilton, resolves the paradox for altruism directed at relatives. Genes for altruism can spread if the benefit to related recipients (who share those genes) exceeds the cost to the altruist, weighted by degree of relatedness. A gene that causes you to sacrifice yourself to save three siblings (who share half your genes) is actually serving its own propagation. Kin selection explains why we reliably help family members, even at significant personal cost.

The reciprocal altruism theory, proposed by Robert Trivers, explains altruism among non-relatives. In social species with repeated interactions, helping others creates obligations that may be repaid later. “I scratch your back, you scratch mine” is not mere folk wisdom but an evolutionarily stable strategy. Altruism toward non-kin is an investment in future assistance, a form of social credit that pays dividends over time.

The group selection theory takes a more controversial position. While individual selection favors selfishness, groups composed of altruists may outcompete groups of selfish individuals. If between-group competition is strong enough relative to within-group competition, altruistic traits can spread even when they disadvantage individual carriers. Tribes with more altruists might win wars, acquire more resources, and expand at the expense of tribes dominated by selfish individuals.

An additional theory concerns reputation and signaling. Altruistic behavior, particularly conspicuous altruism, signals underlying qualities—resources, status, prosocial orientation—that make the altruist more attractive as a mate, ally, or group member. The costs of altruism are repaid through enhanced reputation and the social opportunities that reputation provides. Altruism is costly advertising of desirable traits.

These theories combine to explain altruism through genetic relatedness, expectation of reciprocation, group-level competition, and reputational benefits. Different forms of altruism may be explained by different mechanisms: helping family by kin selection, helping friends by reciprocity, helping strangers perhaps by reputation or group selection.

The mysterious variable is anonymous altruism. People sometimes help others in contexts where no reputational benefit is possible—anonymous donations, aid to individuals they will never see again, assistance when no one is watching. If all altruism served genetic, reciprocal, group, or reputational interests, truly anonymous altruism should not exist. Yet it does. Whether this represents expanded psychology (empathy mechanisms that “misfire” beyond adaptive contexts), cultural conditioning, or something else about human nature that transcends evolutionary calculation remains an open question.

Why Do We Feel Nostalgia?

Nostalgia was once classified as a medical condition—a form of melancholia that afflicted displaced persons, particularly soldiers and migrants longing for home. Swiss physician Johannes Hofer coined the term in 1688 from the Greek nostos (homecoming) and algos (pain). For centuries, nostalgia was considered a disease to be treated. Today, psychological research has rehabilitated nostalgia as a fundamentally healthy phenomenon—a coping resource with measurable psychological benefits. But why do we feel it at all?

The existential buffer theory, developed by researchers including Constantine Sedikides at the University of Southampton, proposes that nostalgia serves terror management functions. When we face reminders of death, irrelevance, or meaninglessness, nostalgic memories provide evidence that our lives have had significance and continuity. The warm glow of remembered experiences counteracts existential anxiety by demonstrating that we have been loved, have belonged, have mattered.

The homeostatic correction theory focuses on nostalgia’s regulatory function. Research has shown that nostalgia is triggered by specific negative states—loneliness, cold, disconnection—and that experiencing nostalgia ameliorates these states. Lonely people who engage in nostalgic reflection report feeling less lonely afterward. Participants in cold rooms who think nostalgically perceive the temperature as warmer. Nostalgia functions as a psychological thermostat, automatically activating to restore emotional equilibrium.

The adaptation failure theory takes a more critical view. Nostalgia might represent a refusal to accept present circumstances—a psychological retreat into an idealized past that prevents full engagement with current reality. From this perspective, nostalgia is not a coping resource but a coping failure, a form of temporal escapism that interferes with present adaptation.

An additional theory concerns social connectedness maintenance. Nostalgic memories typically involve other people—family, friends, romantic partners, communities. By revisiting these memories, we maintain psychological contact with our social networks across time. Nostalgia may function to keep us bonded to absent others, maintaining relational continuity even when physical contact is impossible.

These theories synthesize into a picture of nostalgia as a multifunctional psychological resource: buffering existential anxiety, regulating emotional states, maintaining social connectedness—though perhaps sometimes at the cost of present engagement.

The mysterious variable is nostalgic idealization. Nostalgic memories are typically more positive than the experiences they represent actually were. We remember the good parts of the past while forgetting or minimizing the difficulties. Why does memory systematically distort the past in this positive direction? And is this distortion a feature (making the past available as a psychological resource) or a bug (preventing accurate learning from experience)? The relationship between nostalgia’s benefits and its inaccuracies remains poorly understood.

Why Do We Believe in the Supernatural?

Every human culture that has ever been studied has included beliefs in supernatural agents—gods, spirits, ghosts, ancestors, demons. This universality across otherwise vastly different societies suggests that supernatural belief is not merely cultural artifact but reflects something fundamental about human cognition. What is it about the human mind that generates these beliefs so reliably?

The Hyperactive Agency Detection Device (HADD) theory, developed by cognitive scientist Justin Barrett, proposes that supernatural beliefs are a byproduct of adaptive cognitive mechanisms. Throughout evolution, it was safer to assume that a rustling in the bushes was a predator than to assume it was wind—false positives were less costly than false negatives. This resulted in cognitive systems biased toward detecting agency, toward assuming that events are caused by intentional beings rather than random forces. Ghosts and gods are what happens when these agency-detection systems misfire in contexts where no agent is actually present.

The social functionalism theory focuses on the behavioral effects of supernatural beliefs. Belief in invisible watchers—gods or spirits who see and judge human behavior—promotes cooperation and norm compliance in ways that benefit groups. Communities of believers may have cooperated more effectively than communities of skeptics, spreading both the beliefs and the genes of believers. Religion is adaptive not because gods exist but because believing in them makes groups function better.

The terror management theory connects supernatural belief to death anxiety. The awareness of mortality, unique to humans, creates existential terror that would be paralyzing without some mechanism of management. Beliefs in afterlife, in continuation of consciousness beyond death, in transcendent meaning—these beliefs buffer the terror of annihilation. We believe in the supernatural because the alternative—fully absorbing our own mortality—is psychologically unbearable.

An additional theory concerns cognitive byproduct accumulation. The human mind has many cognitive features—theory of mind (attributing mental states to others), dualism (intuiting that minds are separate from bodies), teleological thinking (assuming things exist for purposes). Each of these features evolved for adaptive reasons unrelated to religion, but together they create minds primed to conceptualize invisible minds, disembodied spirits, and purposeful universes. Supernatural belief is what happens when cognitive adaptations combine in unintended ways.

These theories converge on supernatural belief as emerging from agency detection biases, group-beneficial social functions, death anxiety management, and the combination of various cognitive features—multiple sources feeding into a universal human phenomenon.

The mysterious variable is the specific content of beliefs. HADD explains why we detect agents; it does not explain why we develop elaborate theologies with specific properties and personalities. Social functionalism explains why beliefs might spread; it does not explain why the particular forms they take vary so dramatically across cultures while sharing structural similarities. Why gods? Why these gods? The specific content of supernatural beliefs—their elaborate specificity—exceeds what purely cognitive or functional theories predict.

Why Do We Like Sad Music?

We spend our lives avoiding sadness. We seek pleasure, pursue happiness, flee from grief. Yet we pay money to feel sad—attending tragic operas, listening to melancholy ballads, streaming playlists designed to provoke tears. The popularity of sad music represents an apparent paradox: voluntary exposure to negative emotions that we otherwise assiduously avoid. What could explain this seemingly irrational behavior?

The prolactin release theory offers a biochemical explanation. Research suggests that experiencing sadness, even artificial sadness, triggers the release of prolactin—a hormone associated with comfort, bonding, and emotional recovery. Sad music tricks the brain into releasing this comforting hormone in response to “phantom” distress. The sad music creates the feeling without the genuine loss, giving us the prolactin benefit without the actual pain. We feel sad, but we feel good about feeling sad.

The social assurance theory proposes that sad music addresses a fundamental human fear: the fear of being alone in our suffering. When we hear a song that expresses grief, loneliness, or heartbreak, we receive evidence that others have felt what we feel—that our emotional experiences are shared rather than isolating. Sad music provides the comfort of knowing we are not alone, that our feelings are part of the human condition rather than aberrant or shameful.

The safe simulation theory frames sad music as emotional exercise. Just as physical exercise stresses the body to build resilience, emotional simulation through art may stress the emotional system in ways that build psychological resilience. Sad music allows us to practice grief, to rehearse the emotional patterns of loss, without actual loss occurring. When real sadness comes, we may be better equipped to navigate it having practiced through music.

An additional theory concerns beauty in the expression of authentic emotion. Sad music is often among the most melodically and lyrically sophisticated—the art form seems to reach its highest expression in melancholy. We may be responding not primarily to sadness but to beauty, and beauty happens to be most achievable when expressing the deepest human emotions. The sadness is a vehicle for aesthetic experience that would not be available through cheerful content.

These theories integrate into a picture where sad music provides hormonal comfort, social connection, emotional rehearsal, and access to aesthetic beauty—multiple rewards that compensate for and perhaps transcend the negative valence of the sadness itself.

The mysterious variable is individual variation in response. Some people love sad music; others actively avoid it. Some find it cathartic; others find it depressing. What determines whether sad music functions as comfort or contagion for any given individual? The personality and situational factors that predict response to sad music—and why some seem to benefit while others suffer—remain poorly mapped.

Part IV: Sensory and Perceptual Mysteries

Why Do We Experience Phantom Limb Pain?

How can a body part that no longer exists hurt? Following amputation, the vast majority of patients report sensations in the missing limb—not merely awareness that it once existed, but vivid feelings of position, movement, and often excruciating pain. Some feel the phantom limb as clenched in an agonizing position; others feel burning, crushing, or stabbing sensations in flesh that is no longer there. This phenomenon challenges our basic assumptions about the relationship between body and perception.

The cortical remapping theory focuses on brain plasticity. The somatosensory cortex contains a “map” of the body, with different regions processing sensations from different body parts. When a limb is lost, its cortical territory becomes available. Adjacent regions—typically the face and upper arm, in the case of hand amputation—may invade this territory. The brain, receiving signals from the face, may misinterpret them as coming from the absent hand. This remapping explains why touching the face can sometimes produce sensations in the phantom limb.

The proprioceptive memory theory proposes that the nervous system retains a “memory” of the limb’s last position and sensations, particularly when amputation followed traumatic injury. If the limb was clenched in pain at the moment of loss, the brain may continue generating that pain signal indefinitely, unable to update its model of the limb because the limb no longer exists to provide corrective feedback. The phantom pain is the brain’s last memory, played on endless loop.

The sensory conflict theory frames phantom pain as an error signal. The brain expects to receive coordinated input from multiple sources—visual confirmation that the hand is moving, proprioceptive signals from the muscles, sensory feedback from the skin. When the limb is gone, these channels conflict. The brain may interpret this conflict, the failure of expected signals to arrive, as evidence of damage or danger, generating pain as an alarm. The phantom pain is the sound of the brain’s error-detection systems screaming about missing data.

An additional theory involves central sensitization. Following amputation, the spinal cord and brain may become hypersensitive to remaining sensory input, amplifying normal signals into pain signals. The neural pathways that once carried information from the limb do not simply go silent; they become hyperactive, generating spontaneous signals that the brain interprets as originating from the absent limb.