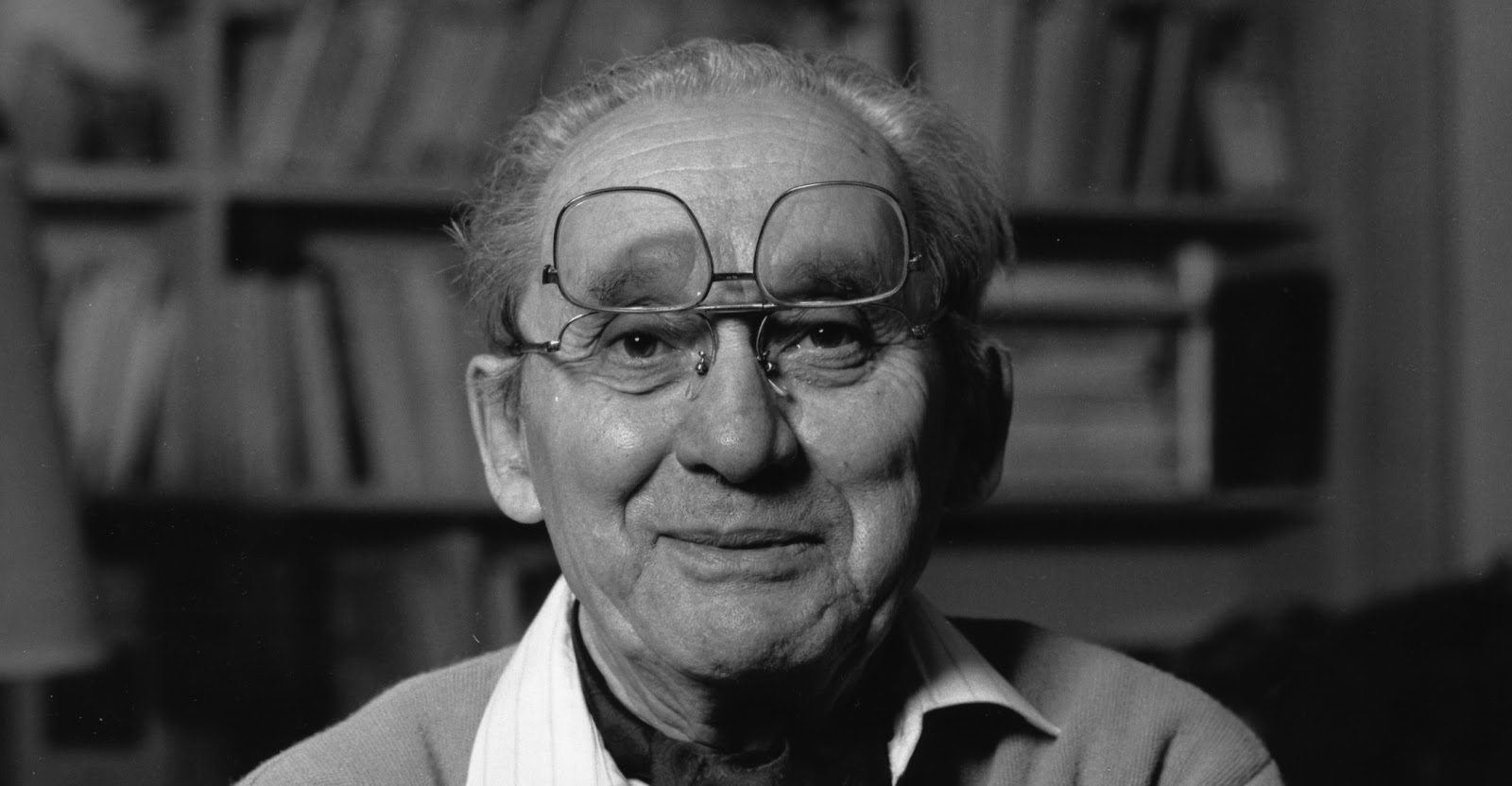

Who was Paul Ricouer?

Paul Ricoeur (1913-2005) was one of the most influential French philosophers of the 20th century. His wide-ranging work made major contributions to the fields of phenomenology, hermeneutics, existentialism, theology and literary theory. Ricoeur is known for his analysis of language and narrative as fundamental to human understanding and identity. His insights reshaped debates around interpretation theory, selfhood, memory, history and ethics.

This comprehensive essay explores Ricoeur’s key ideas and their impact. It examines his theory of interpretation, narrative identity, and approach to ethics and justice. The continued relevance of Ricoeur’s thought for contemporary philosophy and other disciplines is discussed. Throughout, the profound originality and synthetic power of Ricoeur’s work is highlighted.

Ricoeur’s Hermeneutic Philosophy

2.1 The Primacy of Language and Discourse

Language was the primary medium of philosophical reflection for Ricoeur. He viewed discourse – the contextual usage of language by speakers – as revelatory of human reality in a way that abstract linguistic systems are not. Ricoeur’s analysis of metaphor and his narrative theory grew from this focus on language-in-use.

For Ricoeur, language is not a neutral tool but actively shapes meaning and understanding. Linguistic expressions carry symbolic meanings that exceed their literal sense. Metaphors, for example, create new meanings by describing one thing in terms of another. This semantic innovation points to the creative power of language.

2.2 Interpretation Theory

Building on this dynamic view of language, Ricoeur developed an influential theory of interpretation or hermeneutics. For him, the goal of interpretation is to uncover the “surplus of meaning” implicit in discourse. The text is not a static object but a mediation between the author’s intentions, the autonomous meanings of the work itself, and the understanding of the reader.

Ricoeur rejected the Romanticist ideal of an intuitive grasp of the author’s creative genius. Instead, he saw interpretation as a dialectical interplay between distanced explanation and participatory understanding. The interpreter’s horizon fuses with the world projected by the text, leading to appropriation of its meanings into the interpreter’s self-understanding.

2.3 Critique of the Cogito

Ricoeur’s hermeneutics led him to question the modern philosophical emphasis on self-consciousness. From Descartes to Husserl, the self-certain subject or cogito was taken as the foundational starting point for philosophical reflection. Against this tradition, Ricoeur argued for the primacy of language over subjectivity.

Self-understanding, for Ricoeur, is always mediated by signs, symbols and texts. There is no immediate self-transparency of reflection. The cogito discovers itself only through the long detour of interpreting the linguistic and cultural works in which it expresses itself. In place of an abstract ego, Ricoeur posits a self that understands itself through engagement with the symbolic mediations of human culture.

Narrative Identity and Selfhood

3.1 Narrative as the Key to Personal Identity

Ricoeur’s most influential concept is arguably that of narrative identity. In his major works Time and Narrative (1983-1985) and Oneself as Another (1990), he proposes that self-identity is constituted by narratives. We understand ourselves by telling stories about our lives.

For Ricoeur, narrative is not just a literary form but a fundamental structure of human experience. It synthesizes the heterogeneous elements of action – agents, goals, means, interactions, circumstances and outcomes – into a meaningful whole. Narrative mediates between the descriptive and prescriptive aspects of action, between what is and what ought to be.

Personal identity, then, has the form of a narrative quest. The self strives to discover a meaningful life-story that can integrate the discordant events of its existence. Selfhood is an ongoing process of interpreting oneself in light of the narratives – historical, fictional, cultural – that one appropriates as one’s own.

3.2 The Dialectic of Sameness and Selfhood

Ricoeur distinguishes two aspects of personal identity – idem (sameness) and ipse (selfhood). Idem-identity refers to the stable, objective qualities that allow us to identify a person as the same over time. Ipse-identity is the reflexive, self-constituting pole of identity as an ongoing narrative quest.

Ricoeur sees selfhood as a dialectical interplay between these two poles. We are not just a fixed character defined by lasting dispositions, nor are we a completely protean self constantly reinventing itself. Narrative identity occupies a middle ground – it has a certain stability but remains open to change and reinterpretation.

This dialectic also structures Ricoeur’s view of ethics. He contrasts the deontological emphasis on moral norms (the self as obedient to universal laws) with the teleological pursuit of the good life (the self as engaged in realizing value). Ethical selfhood emerges from the back-and-forth between these two dimensions.

3.3 Recognition and Intersubjectivity

For Ricoeur, selfhood is fundamentally intersubjective. We become selves through our interactions with others who recognize us. Drawing on Hegel, he sees mutual recognition as crucial to achieving full self-consciousness.

Ricoeur expands the idea of recognition to include not just interpersonal relations but our participation in social institutions. We recognize ourselves in the institutions – political, legal, cultural – that reflect shared meanings and values. Institutional roles and narratives shape the identities we can adopt.

At the same time, Ricoeur stresses that recognition must be mutual and reciprocal to be genuine. The struggle for recognition drives social and political conflicts. Groups denied equal recognition will demand it, as in anti-colonial or feminist movements. Just institutions must ensure recognition is truly mutual.

Ethics, Justice and Memory

4.1 The Primacy of Ethics

Ricoeur’s later work increasingly focused on ethical and political themes. He aimed to chart a path between Kantian deontology and Aristotelian virtue ethics. His ethical thought revolves around the idea of “aiming at the good life with and for others in just institutions.”

This formula stresses the primacy of ethics over morality. Our ethical aim – the desire for a meaningful, fulfilling life – is more fundamental than moral norms. We turn to moral rules only when this aspiration leads to practical conflicts requiring impartial adjudication. Even then, moral judgments remain rooted in an ethical horizon of value.

4.2 Justice and the Juridical

Ricoeur’s political philosophy centers on the idea of justice. He views the institution of the juridical as a key mediation between the interpersonal and societal dimensions of justice. Legal discourse provides a formalized way of addressing questions of right.

However, Ricoeur insists that justice cannot be reduced to legal norms. It also has a distributive aspect concerned with the equitable allocation of social goods, and a restorative dimension aimed at mending broken communal bonds. Fully realized justice must attend to all these levels.

Ricoeur’s later works Reflection and the Just (1995) and The Just (2000) explore how juridical practices can embody and sustain justice. He examines the role of judges, the symbolic function of legal pronouncements, and the relation between justice and vengeance, forgiveness and clemency.

4.3 Memory, History, Forgetting

Ricoeur’s last major work, Memory, History, Forgetting (2000), engages the ethical and political stakes of our relation to the past. He argues that memory has an intrinsically ethical aim – the duty to remember and do justice to the victims of history.

At the same time, Ricoeur acknowledges the inescapability of forgetting. Memory is finite and fallible. It can be abused, as in ideological distortions of the past. The task of history is to combat false memory through a critical sifting of evidence. Yet historiography too has its limits and cannot fully capture lived experience.

Ultimately, Ricoeur suggests, we must navigate between the extremes of obsessive memory and careless forgetting. An ethics of memory strives to preserve the past’s claim on us while remaining open to the unburdening of forgiveness. This balance allows a wounded society to work through its trauma and imagine a new future.

Influence and Legacy

Ricoeur’s thought has reverberated across a host of disciplines. His hermeneutic theory transformed debates in linguistics, literary studies and theology. Ricoeur’s analysis of narrative revolutionized how theorists conceive of self-identity and its relation to culture. Few ideas have proven as widely influential as Ricoeur’s concepts of metaphor, textual interpretation and narrative identity.

In philosophy, Ricoeur’s creative synthesis of traditions – analytic and continental, ancient and modern – blazed a trail for a more ecumenical style of thinking. The ethical and political dimensions of his later work continue to inspire reflections on justice, law, memory and history. Ricoeur’s call for a “critical philosophy” that engages the practical sphere points the way for socially engaged thought.

Perhaps most profoundly, Ricoeur’s vision of the “capable human” – the self that can speak, act, narrate and take responsibility – offers a powerful alternative to reductive notions of subjectivity. Against modern skepticism and postmodern deconstructions of the subject, Ricoeur reveals the resilient power of language, imagination and action to recreate meaning. His work continues to attest to the enduring human ability to understand oneself and care for others in a fragile but worthwhile world.

Essential Works

Freedom and Nature (1950)

Fallible Man (1960)

The Symbolism of Evil (1960)

Freud and Philosophy (1965)

The Conflict of Interpretations (1969)

The Rule of Metaphor (1975)

Time and Narrative (1983-1985)

Oneself as Another (1990)

Reflection and the Just (1995)

Memory, History, Forgetting (2000)

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

Jungian Topics

How Psychotherapy Lost its Way

Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality?

What Can the Origins of Religion Teach us about Psychology

The Major Influences from Philosophy and Religions on Carl Jung

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing Fiction

How the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jung to Combat Addiction

Jungian Exercises from Greek Myth

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Post Post-Moderninsm and Post Secular Sacred

The Origins and History of Consciousness

Jung’s Empirical Phenomenological Method

The Future of Jungian Thought

Jungian Analysts

Anthropology

Mystics and Gurus

Philosophy

Spirituality

Types of Therapy

Influential Psychologists

0 Comments