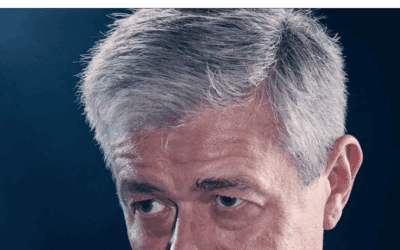

Who was Jacob Burckhardt?

Jacob Burckhardt (1818-1897), the renowned Swiss historian and philosopher of culture, has made an indelible impact on our understanding of the Renaissance, modernity, and the nature of historical change. His groundbreaking works, such as “The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy” (1860) and “Reflections on History” (1868), have not only reshaped the field of cultural history but also provided valuable insights into the psychological dimensions of historical transitions and the role of the individual in shaping the course of civilizations. Burckhardt’s ideas have had a profound influence on subsequent thinkers, including Friedrich Nietzsche, Max Weber, and Sigmund Freud, and continue to inspire scholars and intellectuals across various disciplines.

2. Burckhardt’s Philosophy of History and Culture

2.1. The Idea of Cultural History

At the heart of Burckhardt’s thought lies his innovative approach to cultural history, which departs from the traditional focus on political events, Great Men, and national narratives. Instead, Burckhardt emphasizes the importance of studying the “inner life” of a culture, including its art, religion, customs, and mentalities. He argues that these cultural elements provide a more accurate and comprehensive picture of a historical epoch than the superficial record of political and military affairs.

In “The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy,” Burckhardt applies this cultural-historical approach to the study of the Italian Renaissance, portraying it as a distinct and transformative period marked by the emergence of new forms of individuality, creativity, and secular values. By examining the various aspects of Renaissance culture, from art and literature to politics and social life, Burckhardt presents a vivid and holistic account of this crucial turning point in Western history.

2.2. The Critique of Progress and Modernity

Burckhardt’s philosophy of history is also characterized by a critical stance towards the idea of progress and the self-congratulatory narratives of modernity. In contrast to many of his contemporaries, who celebrated the triumphs of modern civilization and the march of reason, Burckhardt adopts a more skeptical and pessimistic view of historical development.

He argues that the notion of progress is a dangerous illusion that obscures the cyclical and unpredictable nature of historical change. For Burckhardt, history is not a linear process of improvement but rather a series of ups and downs, in which periods of cultural flourishing are inevitably followed by times of decline and dissolution.

Moreover, Burckhardt is deeply critical of the homogenizing and leveling tendencies of modern mass society, which he sees as a threat to individual freedom and cultural diversity. He warns against the rise of the “terrible simplifiers,” the demagogues and ideologues who seek to reduce the complexity of human experience to simple formulas and slogans.

2.3. The Role of the Individual in History

Despite his emphasis on cultural forces and historical patterns, Burckhardt does not neglect the importance of the individual in shaping the course of history. He recognizes that exceptional individuals, through their actions and ideas, can have a profound impact on their times and leave a lasting legacy.

However, Burckhardt’s view of the individual is far from the heroic or romantic conception of the Great Man. Instead, he sees the significant individual as a product of their cultural context, who both reflects and transcends the prevailing values and attitudes of their age. The great figures of history, for Burckhardt, are those who embody the spirit of their time while also possessing the creativity and vision to transform it.

In this sense, Burckhardt anticipates the insights of later thinkers, such as Nietzsche and Freud, who emphasized the complex interplay between individual psychology and cultural forces in shaping human behavior and historical change.

3. Burckhardt’s Psychological Insights

3.1. The Renaissance and the Emergence of the Modern Self

One of Burckhardt’s most significant contributions to the understanding of the modern self lies in his analysis of the Renaissance as a key moment in the development of individualism and subjectivity. In “The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy,” Burckhardt argues that the Renaissance marked a radical break with the collectivism and traditionalism of the Middle Ages, giving rise to a new sense of individual identity and agency.

He traces this emergence of the modern self to various factors, including the rediscovery of classical antiquity, the growth of secular values, and the increasing complexity of social and political life. Burckhardt shows how the Renaissance fostered a new appreciation for human dignity, creativity, and the power of the individual will, as exemplified by figures such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Cesare Borgia.

At the same time, Burckhardt recognizes the darker aspects of this newfound individualism, such as the rise of narcissism, amorality, and the unrestrained pursuit of power. He sees in the Renaissance the seeds of both the grandeur and the fragility of the modern self, torn between the aspirations of genius and the temptations of hubris.

3.2. The Psychology of Cultural Transitions

Burckhardt’s work also offers valuable insights into the psychological dimensions of cultural transitions and the impact of historical change on the individual psyche. He is acutely aware of the disorienting and destabilizing effects of rapid social and cultural transformations, which can leave individuals feeling uprooted and alienated from traditional sources of meaning and identity.

In his analysis of the Renaissance, Burckhardt shows how the breakdown of medieval certainties and the emergence of new ways of thinking and being created a sense of existential anxiety and uncertainty. He describes the “spiritual homelessness” of the Renaissance individual, who is forced to navigate a world of competing values and ideals without the guidance of a stable moral compass.

Burckhardt’s insights into the psychology of cultural transitions anticipate the work of later thinkers, such as Erich Fromm and Erik Erikson, who explored the impact of historical change on individual development and the formation of identity. His analysis of the Renaissance as a period of both opportunity and crisis for the self remains relevant to our understanding of the challenges and possibilities of living in a rapidly changing world.

3.3. The Pathologies of Modern Culture

In addition to his exploration of the positive aspects of individualism and cultural change, Burckhardt is also attuned to the pathological dimensions of modern culture. He is deeply concerned about the loss of meaning and the erosion of values in a world increasingly dominated by materialism, mass politics, and the cult of success.

Burckhardt sees in the modern age a tendency towards the flattening of culture and the reduction of human experience to a narrow range of economic and political imperatives. He warns against the dangers of conformism, mediocrity, and the tyranny of public opinion, which threaten to stifle individual creativity and moral autonomy.

Moreover, Burckhardt anticipates the insights of later psychoanalytic thinkers, such as Freud and Jung, in his recognition of the irrational and destructive forces that lurk beneath the surface of modern civilization. He sees in the mass movements and ideological fanaticism of his time a symptom of the repressed and unacknowledged aspects of the human psyche, which can erupt in violent and catastrophic ways.

In this sense, Burckhardt’s critique of modern culture is not only a historical and philosophical analysis but also a psychological diagnosis of the malaise and discontent that afflict the modern self. His work serves as a warning against the dangers of forgetting the lessons of history and neglecting the cultivation of individual character and cultural values.

4. The Influence of Burckhardt on Subsequent Thinkers

4.1. Nietzsche and the Critique of Modernity

One of the most significant intellectual heirs of Burckhardt is Friedrich Nietzsche, who was deeply influenced by his former teacher’s ideas on history, culture, and the individual. Nietzsche shares Burckhardt’s critical stance towards modernity and his concerns about the leveling and homogenizing tendencies of mass society.

Like Burckhardt, Nietzsche sees in the modern age a crisis of values and a threat to individual greatness and cultural vitality. He develops Burckhardt’s insights into the psychology of cultural transitions and the pathologies of modern culture in his own critique of morality, religion, and the “herd mentality.”

However, Nietzsche also radicalizes and transforms Burckhardt’s ideas in significant ways. While Burckhardt maintains a certain distance and detachment from the historical process, Nietzsche plunges into the heart of modernity and seeks to overcome its limitations through a new kind of individual self-creation and cultural transformation.

4.2. Weber and the Sociology of Culture

Another important thinker who builds on Burckhardt’s legacy is Max Weber, the German sociologist and philosopher. Weber shares Burckhardt’s interest in the cultural dimensions of historical change and the role of ideas and values in shaping social reality.

Like Burckhardt, Weber emphasizes the importance of studying the “inner life” of cultures and the ways in which religious, ethical, and economic beliefs interact with social and political structures. He develops Burckhardt’s insights into the psychology of cultural transitions in his own analysis of the rise of capitalism and the emergence of modern bureaucratic society.

However, Weber also departs from Burckhardt in significant ways. While Burckhardt focuses primarily on the aesthetic and intellectual aspects of culture, Weber is more interested in the institutional and organizational dimensions of social life. He seeks to develop a systematic and comparative approach to the study of cultures and civilizations that goes beyond Burckhardt’s more impressionistic and intuitive methods.

4.3. Psychoanalysis and the Interpretation of Culture

Finally, Burckhardt’s ideas have also had a significant impact on the development of psychoanalysis and the psychoanalytic interpretation of culture. Thinkers such as Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung were deeply influenced by Burckhardt’s insights into the irrational and unconscious aspects of human behavior and the role of myths, symbols, and archetypes in shaping cultural identity.

In particular, Burckhardt’s analysis of the Renaissance as a period of psychological and cultural transformation anticipates the psychoanalytic understanding of the relationship between individual development and historical change. His recognition of the darker aspects of individualism and the pathologies of modern culture also resonates with the psychoanalytic critique of civilization and its discontents.

Moreover, Burckhardt’s emphasis on the importance of studying the “inner life” of cultures and the ways in which ideas and values shape social reality has inspired the psychoanalytic approach to the interpretation of cultural phenomena, from art and literature to politics and religion.

5. Legacy and influence

5.1. Burckhardt’s Enduring Significance

Jacob Burckhardt’s philosophy of history and culture, with its emphasis on the psychological dimensions of historical change and the role of the individual in shaping civilizations, remains a vital and relevant resource for understanding the challenges and possibilities of the modern world.

His insights into the emergence of the modern self, the psychology of cultural transitions, and the pathologies of modern culture continue to inspire and inform contemporary debates about the nature of identity, the meaning of progress, and the future of civilization.

Moreover, Burckhardt’s legacy as a thinker who bridged the gap between historical analysis and psychological inquiry serves as a model for interdisciplinary scholarship and the integration of different perspectives on the human experience.

5.2. The Relevance of Burckhardt’s Ideas for the Contemporary World

In a world marked by rapid technological change, globalization, and the erosion of traditional cultural boundaries, Burckhardt’s warnings about the dangers of homogenization, conformism, and the loss of individual autonomy remain as relevant as ever.

His critique of the cult of progress and the self-congratulatory narratives of modernity also resonates with contemporary concerns about the sustainability and desirability of endless economic growth and the impact of human activities on the natural environment.

At the same time, Burckhardt’s appreciation for the creativity and resilience of the human spirit in the face of historical upheavals and cultural crises offers a source of hope and inspiration for navigating the uncertainties and challenges of the present moment.

5.3. The Importance of Cultural History and Psychological Inquiry

Finally, Burckhardt’s work reminds us of the importance of studying the cultural dimensions of historical change and the psychological aspects of human behavior in order to gain a deeper understanding of the forces that shape our lives and the world around us.

His approach to cultural history, with its emphasis on the “inner life” of cultures and the role of ideas, values, and mentalities in shaping social reality, remains a valuable framework for exploring the complex interplay between individuals, societies, and historical forces.

Moreover, Burckhardt’s insights into the psychological dimensions of cultural transitions and the pathologies of modern culture underscore the need for continued dialogue between historical analysis and psychological inquiry, in order to address the challenges and possibilities of living in a rapidly changing world.

By engaging with Burckhardt’s thought and building on his legacy, we can develop new and more comprehensive perspectives on the human experience, and work towards a deeper understanding of ourselves, our cultures, and the historical processes that shape our lives.

6. Bibliography

Burckhardt, Jacob. “The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy”. Translated by S.G.C. Middlemore. New York: The Modern Library, 2002.

Burckhardt, Jacob. “Reflections on History”. Translated by M.D.H. Liberty Fund Inc., 1979.

Gossman, Lionel. “Basel in the Age of Burckhardt: A Study in Unseasonable Ideas”. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Gossman, Lionel. “Jacob Burckhardt and the Crisis of Modernity”. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000.

Hinde, John R. “Jacob Burckhardt and the Crisis of Modernity”. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000.

Howard, Thomas Albert. “Religion and the Rise of Historicism: W.M.L. de Wette, Jacob Burckhardt, and the Theological Origins of Nineteenth-Century Historical Consciousness”. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Kaegi, Werner. “Jacob Burckhardt: Eine Biographie”. 7 vols. Basel and Stuttgart: Schwabe, 1947-1982.

Krieger, Leonard. “Ranke: The Meaning of History”. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977.

Lerner, Robert E. “Burckhardt’s Jacob”. Renaissance News 12, no. 4 (Winter 1959): 247-252.

Maurer, Michael. “Jacob Burckhardt und die Erfindung der Renaissance. Ein Mythos und seine Geschichte”. Bern: Verlag Hans Huber, 2001.

Murray, John. “Burckhardt and Nietzsche”. In “Jacob Burckhardt and the Renaissance: A Hundred Years Later”, edited by Mack P. Holt, 59-80. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1991.

Picht, Georg. “Die Wirkung Jacob Burckhardts auf die Geistesgeschichte der Gegenwart”. In “Jacob Burckhardt und die Kultur der Renaissance”, edited by Hartmut Baumann and Martin Warnke, 60-80. Berlin: Wagenbach, 1995.

Schorske, Carl E. “Thinking with History: Explorations in the Passage to Modernism”. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998.

Sigurdson, Richard. “Jacob Burckhardt’s Social and Political Thought”. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

Trevor-Roper, Hugh. “Jacob Burckhardt and the Renaissance”. In “Men and Events: Historical Essays”, edited by Hugh Trevor-Roper, 97-117. New York: Macmillan, 1958.

Read More Depth Psychology Articles:

Taproot Therapy Collective Podcast

Jungian Innovators

Jungian Topics

How Psychotherapy Lost its Way

Therapy, Mysticism and Spirituality?

The Symbolism of the Bollingen Stone

What Can the Origins of Religion Teach us about Psychology

The Major Influences from Philosophy and Religions on Carl Jung

How to Understand Carl Jung

How to Use Jungian Psychology for Screenwriting and Writing Fiction

The Symbolism of Color in Dreams

How the Shadow Shows up in Dreams

Using Jung to Combat Addiction

Jungian Exercises from Greek Myth

Jungian Shadow Work Meditation

Free Shadow Work Group Exercise

Post Post-Moderninsm and Post Secular Sacred

The Origins and History of Consciousness

Jung’s Empirical Phenomenological Method

The Future of Jungian Thought

Jungian Analysts

Anthropology

Mystics and Gurus

Philosophy

Spirituality

Types of Therapy

Influential Psychologists

Influences on Jung

Classical Literature

Iphigenia in Aulis

0 Comments